Theory of Fun for Game Design (9 page)

Read Theory of Fun for Game Design Online

Authors: Raph Koster

Tags: #COMPUTERS / Programming / Games

Back in 1976, a company called Exidy scored a first in video game history: its game

Deathrace

was taken off the market because of public concerns about the game’s violent nature.

Deathrace

was loosely based on a movie called

Deathrace 2000

. The premise involved driving a car to run over pedestrians for points.

Mechanically,

Deathrace

was the same as any other game that involved catching objects moving around the screen. If you looked at this game today, however, with its crude pixilated graphics and its tiny iconic people, you wouldn’t be particularly shocked. After all, countless other gore-fests have come along that make the game look quaint.

I don’t think debates about the suitability of violence in the media will disappear. Much evidence shows that media have some effect on how we act. If media didn’t have an effect, we wouldn’t spend so much effort on using it as teaching tools. But evidence also shows that media aren’t mind-control devices (of course they aren’t, or else we’d all behave like the people we read about in the children’s stories we read in elementary school).

Gamers, however, have always viewed this issue with some perplexity. When they defend their beloved games, they use one of the most self-defeating rallying cries in history: “It’s only a game!”

In the wake of school shootings and ex-military people decrying first-person shooters as “murder simulators,” this argument doesn’t carry a lot of weight. Academics who disagree with the portrayal of games as damaging to children tend to muster learned arguments about privileged spaces and magic circles. Much of the public dismisses these arguments as coming from an ivory tower.

But there’s a very good reason why the gamers are incredulous.

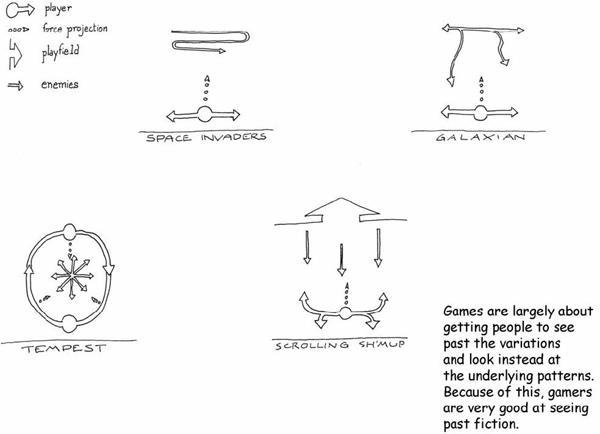

Remember, games train us to see underlying mathematical patterns. The fact that I can describe

Deathrace

as being a game about picking up objects on a two-dimensional playing field is evidence that its “dressing” is largely irrelevant to what the game is about at its core. As you get more into a game, you’ll most likely cut to the chase and examine the true underpinnings of the game, just as a music aficionado can cut past the lyrical content of different types of Latin music and determine whether a given song is a

cumbia

or a

marinera

or a

salsa

.

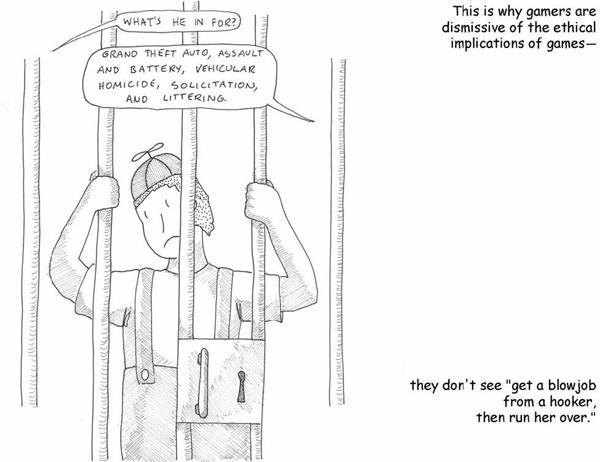

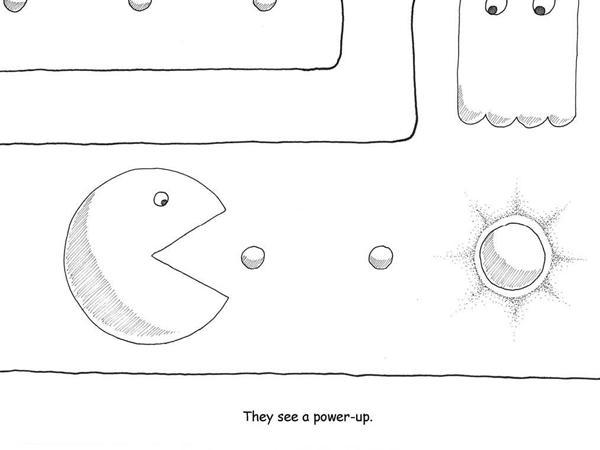

Running over pedestrians, killing people, fighting terrorists, and eating dots while running from ghosts are all just stage settings, convenient metaphors for what a game is actually teaching.

Deathrace

does not teach you to run over pedestrians any more than

Pac-Man

teaches you to eat dots and be scared of ghosts.

None of this is to minimize the fact that

Deathrace does

involve running over pedestrians and squishing them into little tombstone icons. That’s there, for sure, and it’s kind of reprehensible. It’s not a great setting or staging for the game, but it’s also not what the game is really about.

Learning to see that division is important to our understanding of games, and I’ll touch on it at greater length later. For now, suffice it to say that the part of games that is

least

understood is the formal abstract system portion of it, the mathematical part of it, the chunky part of it. Attacks on other aspects of games are likely to miss the key point—at their core games need to develop this formal aspect of themselves in order to improve.

Alas, that isn’t what we tend to focus on.

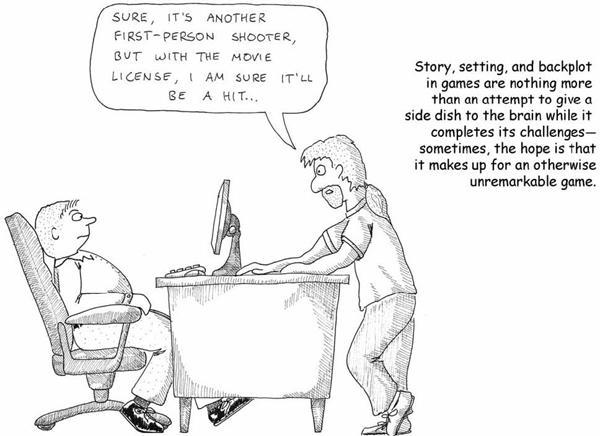

The commonest route these days for developing games involves grafting a story onto them. But most video game developers take a (usually mediocre) story and put little game obstacles all through it. It’s as if we are requiring the player to solve a crossword puzzle in order to turn the page to get more of the novel.

By and large, people don’t play games because of the stories. The stories that wrap the games are usually side dishes for the brain. For one thing, it’s damn rare to see a game story written by an actual writer. As a result, they are usually around the high-school level of literary sophistication at best.

For another, since the games are generally about power, control, and those other primitive things, the stories tend to be so as well. This means they tend to be power fantasies. That’s generally considered to be a pretty juvenile sort of story.

The stories in most video games serve the same purpose as calling the über-checker a “king.” It adds interesting shading to the game but the game at its core is unchanged.

Remember—my background is as a writer, so this actually pisses me off. Story deserves better treatment than that.

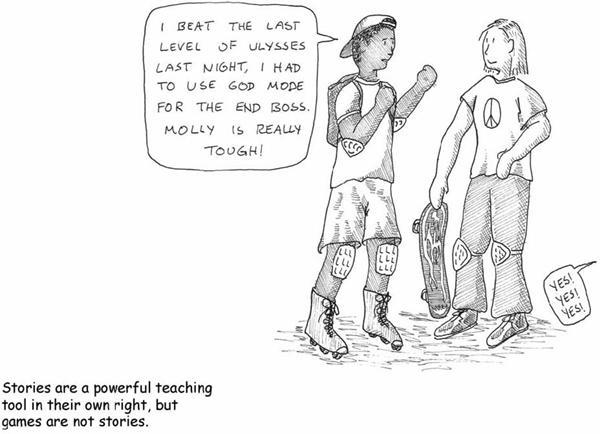

Games are not stories. It is interesting to make the comparison, though:

- Games tend to be experiential teaching. Stories teach vicariously.

- Games are good at objectification. Stories are good at empathy.

- Games tend to quantize, reduce, and classify. Stories tend to blur, deepen, and make subtle distinctions.

- Games are external—they are about people’s actions. Stories (good ones, anyway) are internal—they are about people’s emotions and thoughts.

In both cases, when they are good, you can come back to them repeatedly and keep learning something new. But we never speak of fully mastering a good story.

I don’t think anyone would quarrel with the notion that stories are one of our chief teaching tools. They might quarrel with the notion that play is the other and that mere lecturing runs a distant third. I also don’t think that many would quarrel with the notion that stories have achieved far greater artistic heights than games have, despite the fact that play probably

predates

story (after all, even animals play, whereas stories require some form of language).

Are stories superior? We often speak of wanting to make a game that makes players cry. The classic example is the text adventure game

Planetfall

, where Floyd the robot sacrifices himself for you. But it happens outside of player control, so it isn’t a challenge to overcome. It’s grafted on, not part of the game. What does it say about games that the peak emotional moment usually cited actually involves

cheating

?

Games do better at emotions that relate to mastery. Stories can get these too, however. Getting emotional effects out of games may be the wrong approach—perhaps a better question is whether stories can be fun in the way games can.

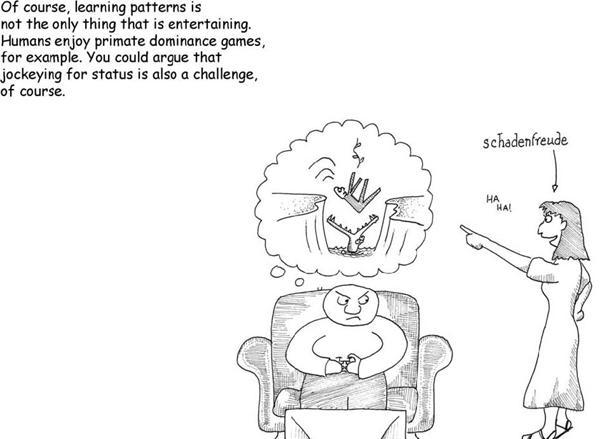

When we speak of enjoyment, we actually mean a constellation of different feelings. Having a nice dinner out can be fun. Riding a roller coaster can be fun. Trying on new clothes can be fun. Winning at table tennis can be fun. Watching your hated high school rival trip and fall in a puddle of mud can be fun. Lumping all of these under “fun” is a rather horribly vague use of the term.

Different people have classified this differently. Game designer Marc LeBlanc has defined eight types of fun: sense-pleasure, make-believe, drama, obstacle, social framework, discovery, self-discovery and expression, and surrender. Paul Ekman, a researcher on emotions and facial expressions, has identified literally dozens of different emotions—it’s interesting to see how many of them only exist in one language but not in others. Nicole Lazzaro did some studies watching people play games, and she arrived at four clusters of emotion represented by the facial expressions of the players: hard fun, easy fun, altered states, and the people factor.

My personal breakdown would look a lot like Lazzaro’s:

- Fun

is the act of mastering a problem mentally. - Aesthetic appreciation

isn’t always fun, but it’s certainly enjoyable. - Visceral reactions

are generally physical in nature and relate to physical mastery of a problem. - Social status maneuvers

of various sorts are intrinsic to our self-image and our standing in a community.

All of these things make us feel good when we’re successful at them, but lumping them all together as “fun” just renders the word meaningless. So throughout this book, when I have referred to “fun,” I’ve meant only the first one: mentally mastering problems. Often, the problems mastered are aesthetic, physical, or social, so fun can appear in any of those settings. That’s because all of these are feedback mechanisms the brain gives us for successfully exercising survival tactics.