Theory of Fun for Game Design (7 page)

Read Theory of Fun for Game Design Online

Authors: Raph Koster

Tags: #COMPUTERS / Programming / Games

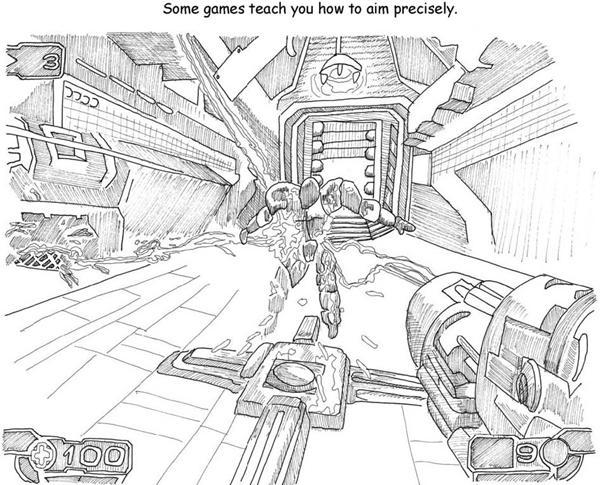

Think about it; teamwork is a far deadlier tool than sharpshooting.

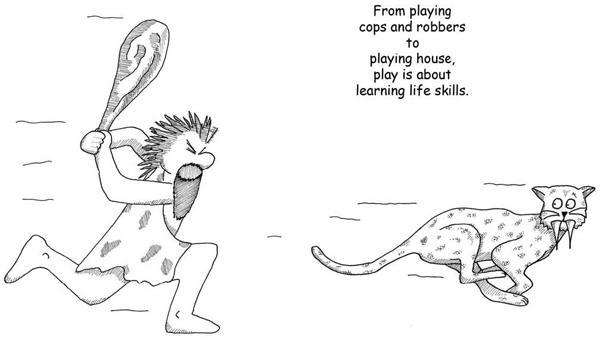

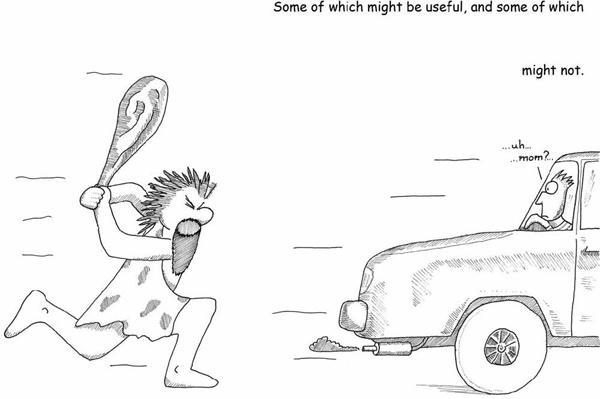

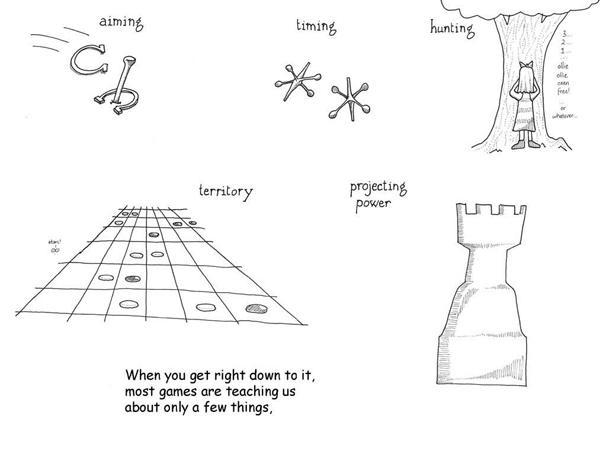

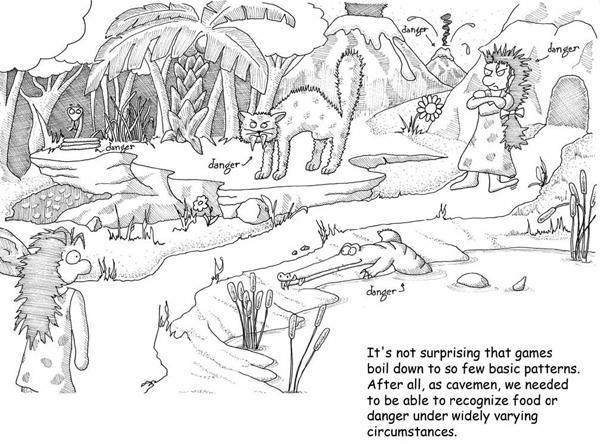

Many games, particularly those that have evolved into the classic Olympian sports, can be directly traced back to the needs of primitive humans to survive under very difficult conditions. Many things we have fun at doing are in fact training us to be better cavemen. We learn skills that are antiquated. Most folks never need to shoot something with an arrow to eat, and we run marathons or other long races mostly to raise funds for charities.

Nonetheless, we have fun mostly to improve our life skills. And while there may be something deep in our reptile brains that wants us to continue practicing aiming or sentry-posting, we do in fact evolve games that are more suited to our modern lives.

For example, there are many games in my collection that relate to network building. Building railway lines or aqueducts wasn’t exactly a caveman activity. As humans have evolved, we’ve changed around our games. In early versions of chess, queens weren’t nearly as powerful a piece as they are today.

Many games have become obsolete and are no longer played. Grain harvesting used to be a really big deal, but it isn’t now. You can’t find many games about farming on the market as a result. In general, the level of mathematical sophistication required by games has risen dramatically over the course of human history as common people learned how to do sums. Word games were once restricted to the elite, but today they are enjoyed by the masses.

Games do adapt, but perhaps not as fast as we might wish, since almost all of these games are still, at their core, about the same activities even though they may involve different skill sets.

In some ways games can be compared to music (which is even more mathematically driven). Music excels at conveying only a few things—emotion being paramount among them. Games do very well at active verbs: controlling, projecting, surrounding, matching, remembering, counting, and so on. Games are also very good at quantification.

By contrast, literature can tackle all of the above and more. Over time, language-based media have tackled increasingly broader subjects.

Games are also capable of modeling situations of greater richness and complexity. Games like

Diplomacy

are evidence that remarkably subtle interactions can be modeled within the confines of a rule set, and traditional role-playing can reach the same heights as literature in the right hands. But it is an uphill battle nonetheless, simply because games are at their core about teaching us survival skills. As we all know, when you’re worried about subsistence and survival, more refined things tend to fall by the wayside.

It’s worth asking ourselves what skills are more commonly needed today. Games should be evolving toward teaching us those skills.

The entire spread of games for children is fairly limited and hasn’t changed much. The basic skills needed by children are the same. Perhaps we need a few more games about changing TV channels, but that’s about it. Adults, on the other hand, could use new games that teach more relevant skills. Most of us no longer hunt our own food and we no longer live in danger every moment of our lives. It’s still valuable to train ourselves in some of the caveman traits, but we need to adapt.

Some traits are relevant but need to change because conditions have changed. Interesting research has been done into what people find disgusting, for example. Disgust is a survival trait that points us away from grayish-green, mucousy, slimy things. It does so because that was the most likely vector for illness.

Today it might be the electric blue fluid that is the real risk—don’t drink any drain cleaner—and we have no inborn revulsion toward it. In fact, it’s made electric blue to make it seem aseptic and clean. That’s a case where we should supplement our instincts with training, since I doubt there’s anything I can drink under my kitchen sink.

Some of the new patterns we need to learn in our brave new world run contrary to our instinctive behaviors. For example, humans are tribal creatures. We not only fall readily into groups run by outsize personalities, but we’ll often subsume our better judgment in doing so. We also seem to have an inbred dislike of groups not our own. It is very easy to get humans to regard a different tribe as less than human, particularly if they look or act differently in some way.

Maybe this was a survival trait at one time, but it’s not now. Our world grows ever more interdependent; if a currency collapse occurs on the other side of the world, the price of milk at our local grocery could be affected. A lack of empathy and understanding of different tribes and xenophobic hatred can really work against us.

Most games encourage demonizing the opponent, teaching a sort of ruthlessness that is a proven survival trait. But these days, we’re less likely to need or want the scorched-earth victory. Can we create games that instead offer us greater insight into how the modern world works?

If I were to identify other basic human traits that games currently tend to reinforce and that may be obsolete legacies of our heritage, I might call out traits like

- Blind obedience to leaders and cultism

- Rigid hierarchies

- Binary thinking

- The use of force to resolve problems

- Like seeking like, and its converse, xenophobia

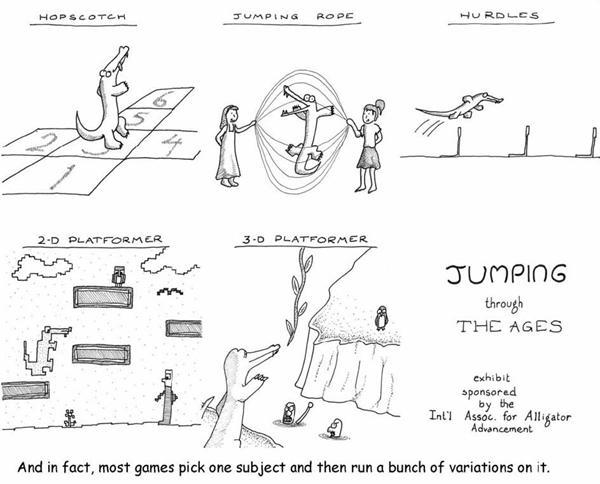

For better or worse, games have been ringing changes on the same few subjects. There’s probably something deep in the reptile brain that is deeply satisfied by jumping puzzles, but you’d think that by now we would have jumped over everything in every possible way.

When I first started playing games, everything was tile based, meaning that you moved in discrete squares, as if you were popping from tile to tile on a tiled floor. Nowadays you move in a much freer way, but what has changed is the fidelity of the simulation, not what we’re simulating. The skills required are perhaps closer to being what they are in reality, and yet an improvement in the simulation of crossing a pond full of alligators is not necessarily something relevant.

The mathematical field of studying shape and the way in which apparent shapes can change but remain the same is called

topology

. It can be helpful to think of games in terms of their topology.

Early platform games followed a few basic gameplay paradigms.

- “Get to the other side” games

.

Frogger, Donkey Kong, Kangaroo

. These are not really very dissimilar. Some of these featured a time limit, some didn’t. - “Visit every location” games

. Probably the best known early platformer like this was

Miner 2049er, Pac-Man

and

Q*Bert

also made use of this mechanic. The most cerebral of these were probably

Lode Runner

and

Apple Panic

, where the map traversal could get very complex given the fact that you could modify the map to a degree.

Games started to meld these two styles, then they added scrolling environments. Eventually designers added playing in 3-D on rails and finally made the leap to true 3-D with

Mario 64

.