There Must Be Murder (8 page)

Read There Must Be Murder Online

Authors: Margaret C. Sullivan

Tags: #jane austen, #northanger abbey, #austen sequel, #girlebooks

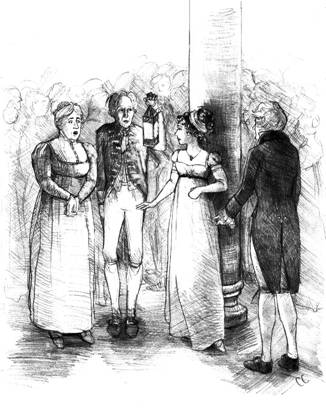

“Mrs. Tilney,” said a familiar voice, low and

familiar, in her ear. She jumped, startled, and whirled about to

see Sir Philip.

“Oh!” she cried. “You startled me!”

“Indeed? If so, I beg your pardon, madam. I

would not make you feel any discomfort for the world; unlike, I

think, some others.”

Catherine had no idea what he meant, and looked

her surprise.

“Do you not understand me? Ah, you are young;

but I saw your blush tonight when your husband prevented me from

meeting you. I suspect the apple does not fall far from the tree in

the Tilney family.”

She blushed again, remembering what she had

learnt of Sir Philip. “I beg your pardon, sir, but I must go; Henry

will be looking for me.”

“Oh, well, then. I should not like to be the

agent of unpleasantness for you. Until another time.” He bowed, and

Catherine turned away, confused by his words, only to be startled

by Mrs. Findlay’s manservant, clutching a lamp and leading his

mistress.

Mrs. Findlay looked from Catherine’s blushing

countenance to Sir Philip and back again, and smiled most

unpleasantly. “Oho!” she said. “Caught in the act!”

“You have caught nothing, ma’am. I wish you good

night.” Catherine hastily curtsied and proceeded outside the

theatre as quickly as she could through the thinning crowd.

She met Henry by the door. “What is it?” he said

upon seeing her expression.

“Sir Philip and Mrs. Findlay,” she said. “Please

take me home, Henry.”

“With all possible speed, my sweet.” He put his

arm around her waist and swept her through the crowds and into Lord

Whiting’s carriage, where his lordship and Eleanor waited to

receive her and make her comfortable. Catherine leaned against

Henry’s sleeve and sighed.

“Better now, Cat?” he asked.

“Yes, thank you.”

“What is it, Catherine dearest?” asked Eleanor

gently.

“Sir Philip would talk to me, and though I put

him off, Mrs. Findlay saw us, and I believe she has drawn the wrong

conclusion.”

“Never mind,” said his lordship. “Everyone must

know that Mrs. Findlay’s gossip is nonsense. First, accusations of

murder, and now adultery! No one family has so much melodrama in

these modern times. No one will pay her any mind.”

“I hope you are right,” said Catherine. “I

overheard Miss Beauclerk and Mr. Shaw talking about services that

he performed for her. It sounded most sinister; but I am sure he

only meant making up her potion.” She shook her head. “Such

nonsense! I liked the play very much. Did not you?”

His lordship looked chagrined, and Eleanor

laughed at him. “You paid no attention to it, did you, my

love?”

“Well, no; but that is not why one goes to the

theatre.”

“Catherine likes a play very well,” said

Henry.

His lordship bowed. “Another time I shall be

quiet and let you enjoy it.”

“I could hear perfectly well, sir; I thank you

for inviting me.”

“I am sorry your evening had a sad end,” said

Lord Whiting.

“To make up for tonight,” said Henry, “Tomorrow

we will have our walk. Eleanor, Whiting, will you join us? We

thought to walk along the river and up to Beechen Cliff, retracing

our steps from last year.”

They agreed to meet at the pump-room at noon,

and Catherine’s evening had a happier ending than she would have

thought when she first entered the carriage.

***

At this moment, Emily’s dislike of Count

Morano rose to abhorrence. That he should, with undaunted

assurance, thus pursue her, notwithstanding all she had expressed

on the subject of his addresses, and think, as it was evident he

did, that her opinion of him was of no consequence, so long as his

pretensions were sanctioned by Montoni, added indignation to the

disgust which she had felt towards him. She was somewhat relieved

by observing that Montoni was to be of the party, who seated

himself on one side of her, while Morano placed himself on the

other. There was a pause for some moments as the gondolieri

prepared their oars, and Emily trembled from apprehension of the

discourse that might follow this silence. At length she collected

courage to break it herself, in the hope of preventing fine

speeches from Morano, and reproof from Montoni. To some trivial

remark which she made, the latter returned a short and disobliging

reply; but Morano immediately followed with a general observation,

which he contrived to end with a particular compliment, and, though

Emily passed it without even the notice of a smile, he was not

discouraged.

“

I have been impatient,” said he, addressing

Emily, “to express my gratitude; to thank you for your goodness;

but I must also thank Signor Montoni, who has allowed me this

opportunity of doing so.”

Emily regarded the Count with a look of

mingled astonishment and displeasure.

“

Why,” continued he, “should you wish to

diminish the delight of this moment by that air of cruel

reserve?—Why seek to throw me again into the perplexities of doubt,

by teaching your eyes to contradict the kindness of your late

declaration? You cannot doubt the sincerity, the ardour of my

passion; it is therefore unnecessary, charming Emily! surely

unnecessary, any longer to attempt a disguise of your

sentiments.”

“

If I ever had disguised them, sir,” said

Emily, with recollected spirit, “it would certainly be unnecessary

any longer to do so. I had hoped, sir, that you would have spared

me any farther necessity of alluding to them; but, since you do not

grant this, hear me declare, and for the last time, that your

perseverance has deprived you even of the esteem, which I was

inclined to believe you merited.”

Catherine sat up. “Henry, please read that

again,” she said.

“Which part?”

“Emily’s last part.”

“Very well,” said Henry, and repeated the last

paragraph.

“That is very good,” said Catherine. “It is just

the thing for me to say to Sir Philip when you are not there, do

not you think?”

Henry looked at her, his brow creased. “Did

Beauclerk impose upon you?”

“Oh, no! But I think he has formed a—a wrong

idea. I just need to explain it to him. Do not you think that is a

good way to say it?”

“The meaning could not be clearer.”

“Let me see the book.” She took the volume and

read it over several times, repeating it aloud. She handed the book

back to Henry. “Will you hear me recite?”

“With pleasure.”

“Sir Philip,” said Catherine solemnly, “Hear me

declare, and for the last time, that your perseverance has deprived

you even of the esteem which I was inclined to believe you

merited.”

“Full marks. You make an excellent pupil, my

sweet.”

Catherine laid her head upon his shoulder with a

happy sigh. “Now I shall not be at a loss if he makes me

uncomfortable again. I shall say to myself, ‘What would Emily do?’

and I shall have my guide.”

“You would be better guided by your own good

sense, Cat. There is more worth here,” touching her head gently,

“and here,” brushing his fingers over her heart, “than in all of

Mrs. Radcliffe’s works, charming as they are.” He lifted her chin

gently with a finger and kissed her.

“Oh, Henry,” said Catherine with a sigh. “I do

not want to think about Sir Philip any more.”

“I am very glad to hear it.” He reached out to

extinguish the candle.

Most Alarming Adventures

Catherine prepared for church the next morning

with a lingering expectation that the expedition to Beechen Cliff

would be put off by some emergency; the general requiring his son’s

company, or a summons from the Beauclerks that could not be

ignored. Indeed there was almost a delay, as Eleanor wished to call

briefly in Laura-place to leave a receipt for rosewater cold cream

in which Lady Beauclerk had expressed an interest.

“Matthew can take the note to her ladyship,”

said Henry, and Eleanor, who did not relish that duty, was happy

enough to surrender it. Catherine thought she saw a significant

look pass between Henry and Matthew as the note was handed over,

but it was soon forgotten in a flutter of anticipatory pleasure.

The charm of a country walk with Henry had not abated upon her

marriage, and Catherine was as happy as she had been during a

similar walk a year earlier; it could be argued she was even

happier, as she now had the right to take Henry’s arm and walk

beside him, talk to him and be the first object of his interest; a

state which Henry enjoyed no less than she.

Most of Bath was promenading upon the Royal

Crescent, and they were nearly alone by the river, so Henry let

MacGuffin off the leash. In his delight at being outside and

unrestrained, the Newfoundland reverted to rather puppyish

behavior, cavorting along the edge of the river and chasing some

mallards who lounged on the bank.

The mallards, indignant at their Sunday repose

being spoiled, squawked and flapped their wings at MacGuffin;

undaunted, he barked and teased them, challenging them to a game

they had no desire to play, ending it by the simple expedient of

entering the river and swimming away. MacGuffin stood on the

riverbank, barking after them; there was a splash, and MacGuffin

was in the river, swimming after the ducks.

“I suspected he would end up in the water,” said

Henry, not at all disturbed by his pet’s behavior.

“Oh! Henry! Get him out!” cried his sister.

“Will he not drown?”

“Newfoundlands are famous swimmers, Eleanor. I

have trained Mac to retrieve in the pond at home.”

MacGuffin was indeed a strong swimmer, but the

ducks were in their natural element, and soon outstripped him. He

made a wide turn in the water, became caught a little in the

current—Eleanor gasped, and Catherine’s heart was in her mouth—but

he soon was climbing up onto the riverbank and running back towards

them, bounding with energy and canine happiness.

“That will do very well, lad,” said Henry. “You

have had your swim, and now must stay with your master.”

MacGuffin shook himself violently, spraying

water all over them. He stood before them, his fur standing on end;

his tail wagged wildly, thick strings of saliva suspended from his

panting mouth, but his joy was obvious; to Catherine, he looked

almost as though he were laughing. He turned and bounded ahead of

them along the riverbank towards the steep climb up to Beechen

Cliff.

Catherine could not help laughing at the dog’s

comical appearance; her companions, busily employing their

handkerchiefs to dry themselves as best they could, looked at each

other and burst into laughter.

“Trained him to retrieve, did you, Tilney?” said

his lordship. “I think you need to train him a little more.”

“Mac is a good dog,” said Catherine, remembering

how he had tried to protect her from Sir Philip Beauclerk the

previous day. “He is still a puppy, really.”

“Indeed he is; and we must all be forgiven our

youthful trespasses,” said Henry with a smile. Catherine took his

arm once again, and the party proceeded to where MacGuffin stood

waiting for them at the base of Beechen Cliff.

* * *

Lady Beauclerk’s butler gave Matthew a careful

once-over. The young man was clean, plainly dressed, unremarkable

in every way, and his demeanor was respectful; there was no reason

to make him wait outside like a common tradesman. He stood back

from the open door and said, “You may wait here whilst I ascertain

if her ladyship wishes to respond.”

Matthew entered and stood in an out-of-the-way

corner in the entry. The butler nodded approvingly, placed the note

on a silver tray and carried it off.

A maidservant walked past, her arms full of

folded sheets. She paused when she saw Matthew, and her gaze

traveled over his person. “Beg pardon,” she said, curtseying.

Matthew noticed the shapely ankle she managed to

display as she did so, and her no less shapely figure. As she

looked up from the curtsey, she caught his eye boldly, and he

winked at her.