There Must Be Murder (3 page)

Read There Must Be Murder Online

Authors: Margaret C. Sullivan

Tags: #jane austen, #northanger abbey, #austen sequel, #girlebooks

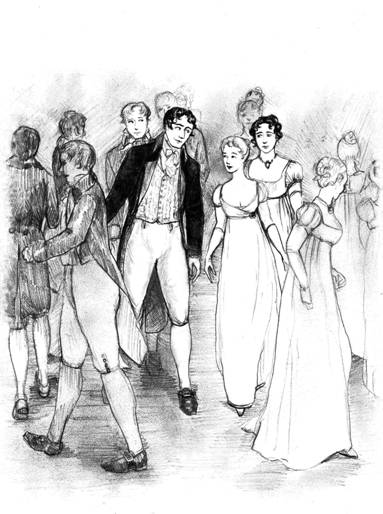

Spoilt by Great Acquaintance

“How do you do, General Tilney?” said Catherine

in a voice that was more composed than she felt.

The general’s answer held the barest hint of

civility. “Very well, I thank you.”

“I am glad to hear it. I am glad that you are

not in Bath for your health, sir.”

Lord Whiting made a noise that sounded

suspiciously like a laugh smothered with a cough.

“Ma’am,” the general said to a woman dressed in

half-mourning who was seated next to him, “May I present Mrs.

Tilney?”

“So this is the paragon that has captured dear

Henry!” the woman cried. “Why, she is adorable! So very

young!

”

“Lady Beauclerk,” the general informed

Catherine, “is a neighbor and a very old friend of the Tilney

family.”

“We so longed to see you when you were staying

at Northanger Abbey last year,” said Lady Beauclerk, fixing

Catherine with her bright eye. “But we were in mourning then for

dear Sir Arthur and not paying calls. But oh, did I wonder about

this Miss Morland who had at last conquered Henry Tilney! The

neighborhood had quite despaired of either of the Tilney boys

finding women good enough to suit their fine taste. I confess I

nurtured a hope that dear Henry might take pity on my Judith and

offer for her. My love,” she called to a young woman who had just

stepped off the dance floor, “come here and be presented to Mrs.

Tilney. I must present you to her, though she is so much younger

than you, for she is a married lady, and you are not.”

Miss Beauclerk was fair and delicate, ethereally

pale; one of those graceful, fluttering creatures who make an

ordinary mortal, even one in a new gown of the most delicate

muslin, feel like a plodding beast. Catherine, confused by Lady

Beauclerk’s speech and disconcerted at meeting this lovely woman

who apparently had once been a rival for her husband’s hand, could

do nothing but curtsy. As she rose, she felt a hand under her

elbow, and knew with a triumphant certainty that Henry stood beside

her.

“We were unprepared to meet so many old friends,

sir,” Henry said to his father, “but I am happy to perform the

introductions for my wife.”

“As you choose,” said the general with every

appearance of fashionable boredom.

“I hope you will not forget to introduce me,

Tilney,” said a young exquisite standing behind Lady Beauclerk’s

chair.

Henry’s hand tightened on Catherine’s elbow

momentarily. “With the greatest pleasure. My sweet, may I present

Sir Philip Beauclerk?”

“Your servant, Mrs. Tilney,” said Sir Philip. He

held out his hand, and Catherine, unsure what else to do, gave him

hers; in a single, graceful movement, Sir Philip bowed and raised

her hand to his lips.

“Henry dear, you are remiss in explaining family

history to dear Mrs. Tilney,” said Lady Beauclerk. “Philip is my

late husband’s nephew and heir, and has put us out of our

home.”

“You will give Mrs. Tilney the idea that I am

the world’s greatest scoundrel, ma’am,” said Sir Philip. “I was

happy to have you and Judith stay on at Beaumont, and am still, but

you would remove to the Dower House.”

“I dare say Mrs. Tilney understands that if I

had only myself to consider, I should have been very happy to stay

and act as your hostess, but it would have been most improper for

Judith to live with her unmarried cousin.”

“As you say, ma’am,” said Sir Philip with

another graceful bow.

“If only you had taken Judith off my hands years

ago, Henry! The least you can do is dance with her.”

Well and truly caught, there was nothing else

for Henry to do but request Miss Beauclerk’s hand in the set that

was forming, and nothing for Miss Beauclerk to do but accept, which

she did as gracefully as she did everything. With another squeeze

of the elbow and a significant, apologetic look, Henry was

gone—gone to the dance floor, with another woman on his arm—and

such a lovely woman!

Lord Whiting also gave Catherine an apologetic

look, but she understood it would not have done to stand up again

with him so soon; instead he took Eleanor to the other set forming.

Catherine was left alone, with such feelings of discomfort as can

be imagined: the general set to ignore her, Lady Beauclerk set to

tease her, and Henry gone; but a rescuer was at hand.

Sir Philip stepped close to her, his voice a

murmur for her ear only. “As my aunt has left you bereft of your

partner,” he said, “perhaps you will accept me as a substitute,

however inferior.”

Catherine accepted, all gratitude for such

kindness. She hoped to follow her brother-in-law’s example and join

the other set, but as they passed behind Miss Beauclerk, she

reached out to touch Catherine’s arm. “Mrs. Tilney, will you stand

next to me? Pray pay no attention to my mother’s rattle. Henry—Mr.

Tilney and I have been friends for a long time, and I am very happy

for you both.”

Catherine looked at Henry, who nodded and

smiled; thus assured, she took the place to which she had been

invited.

Sir Philip turned out to be the sort of partner

in whom Catherine normally delighted: a graceful dancer who did

nothing to draw undue attention to himself, scrupulously polite,

certainly handsome; but instead of giving her attention to her

partner, she found herself watching Henry dance with Miss

Beauclerk, watching him lean close to say something that made her

laugh. Common sense told her that in such a crowded room, Henry had

to lean close to be heard, but she could not be comfortable.

Sir Philip did not seek to engage her in

conversation beyond the commonplace civilities of a ballroom, for

which Catherine was grateful, though she felt she should be making

more of an effort. She felt it even more acutely after their two

dances were over, and Mr. King presented gentleman after gentleman

who wished introductions to the pretty young bride who had been

singled out by a man of fashion such as Beauclerk. Catherine danced

with them all, and conversed politely with them all, and was

obliged to speak very severely to one of them, who appeared to be

in liquor and seized her waist with more familiarity than allowed

by a country-dance. Mr. King hustled the offender away directly

with profuse apologies; Catherine heard the man say to the master

of the ceremonies, “But she was dancin’ with Beauclerk!” She could

not begin to understand him.

She had made up her mind to not dance any more

that evening, when Henry appeared before her like a miracle. “I

hope you saved two dances for me,” he said.

“Any two you wish.”

“The next two, then.”

Her flagging spirits revived, they had their two

dances, and then everyone was going in to tea. Though the room was

crowded, Henry managed to find a table, and sent a waiter to fetch

their tea.

“How delightful that we were dancing together

just now,” said Catherine. “I would not have liked to be obliged to

drink tea with someone else just because he happened to be my

partner for the last dance.”

“Nor I, my sweet; and that is why I gave Mr.

King a half-crown to tell me which would be the last dance before

tea.”

Catherine gasped, and then laughed, and poured

her beloved a cup of tea as they were joined by Lord and Lady

Whiting.

“Oh, how very comfortable,” said Eleanor. “Here

we all are together, when we despaired of finding a place!”

“The General will not join us?” asked Henry.

“The General,” said Whiting, “waits upon Lady

Beauclerk’s party, of course.”

Catherine let out a sigh of relief and smiled at

Henry.

“Now that we can speak more freely, I may ask:

what brings you all to Bath?” Henry asked, passing a cup of tea to

his sister.

“I wrote to you that we were visiting at the

Abbey over Christmas,” said Eleanor. “My father pressed me to stay

on after the holiday to act as his hostess.”

“What my lovely wife has left out of the story,”

said his lordship, “is that General Tilney needed a hostess at the

Abbey so that he could continue to receive Lady Beauclerk and her

daughter, who have been frequent callers at the Abbey, at least on

the days that the general was not haunting Beaumont.”

“Indeed?” asked Henry, exchanging a speaking

glance with his sister, who bowed her head and sipped her tea. “But

you have not yet answered my question: what brings you all to

Bath?”

His lordship smirked. “Her ladyship thought the

waters might do her good, and the general decided soon after that

the waters would do

him

good.”

“John,” said Eleanor in a warning tone.

“Do not look so despondent, my love,” said his

lordship. “If the general marries Lady Beauclerk, he will no longer

be able to exploit your very proper daughterly scruples to keep you

at the Abbey for months on end. He will have a hostess permanently

installed.”

Eleanor shook her head. “I cannot like it. It is

not seemly, so soon after Sir Arthur’s death.”

“You refine too much upon trifles, my love. You

may be sure that the neighborhood had them married off before Sir

Arthur was cold in his grave. ‘So suitable!’ the old biddies cry.

‘Such old friends! Such fine fortunes!’”

“I know

you

cannot like it, Henry,” said

Eleanor.

“It is none of my affair, I am sure,” said

Henry. “My mother has been dead these ten years. It is not

wonderful that the general should seek a wife.”

“I would have had him look elsewhere.”

“Do we have the right to dictate to him,

Eleanor, when we did not allow him to dictate to us?” said Henry,

with a smile at Catherine.

“But John and Catherine are not—” Eleanor bit

off the words.

“Hateful shrews?” supplied her husband.

Even Eleanor laughed at his sally.

“I would not worry overmuch,” said his lordship,

finishing his tea. “I am not so sure that her ladyship will accept

an offer from General Tilney. She is enjoying single blessedness

too much to give it up very soon. Do you know what they call her?

The Merry Widow.”

“Do they indeed?” murmured Henry.

Catherine did not expect much enjoyment from the

remainder of the evening, but more dances with the viscount, and

Sir Philip, and especially with Henry, brought back all the

happiness with which she had anticipated this visit to Bath,

alloyed only by Miss Beauclerk taking Catherine’s hand at the close

of the ball and begging her to call at their house in Laura-place

on the morrow. Her manner was so perfectly frank and friendly that

Catherine could not refuse, though she shrank from a more intimate

acquaintance.

Matthew and MacGuffin waited for them outside

the rooms; Matthew had already procured a chair for Catherine, but

Henry walked ahead of the chair, deep in conversation with Matthew,

who held a lantern to light the way. The chair-men kept a careful

distance, unsure what to make of the very large Newfoundland dog,

so their progress was slower than usual.