There Must Be Murder (2 page)

Read There Must Be Murder Online

Authors: Margaret C. Sullivan

Tags: #jane austen, #northanger abbey, #austen sequel, #girlebooks

Catherine did not immediately notice Henry’s

entrance. She lay upon the sofa in an attitude that even the most

generous observer might consider unladylike: her chin rested upon

her hands, which were crossed over the arm of the sofa, and a

slippered foot extended carelessly from a froth of petticoats as

she gazed out of one of the big windows towards the little cottage

beyond the orchard. She had been reading, but the forgotten book

had dropped to the floor, where Ruby Begonia, the terrier most

attached to Catherine, slept in a patch of sunlight. Henry wondered

what made her smile so; his vanity did not extend to imagining that

she was thinking of him.

He said her name; she started, and then laughed.

“You have caught me daydreaming!” Ruby Begonia yawned, stretched,

and jumped up to run to her master to have her ears scratched.

Catherine made as if to sit up, but he said,

“Nay, my sweet, stay as you are. I should hate to lose sight of

such a pretty ankle.”

“Henry!” she exclaimed in austere tones as she

sat up and arranged her skirts demurely. She was accustomed to his

teasing, but not yet to the liberties that a husband might

take.

“Well, it is a very pretty ankle; but I suppose

your scruples are as they should be. But that is not why I looked

for you. The post has just arrived, including a letter from

Naughton.” Mr. Naughton was Henry’s curate. They had been fellows

together at Oxford until Henry took over the Woodston living. Mr.

Naughton was content with the academic life, and had no thought of

marriage; however, he had a widowed mother and unmarried sister to

help support, and was happy to receive a yearly stipend in return

for riding to Woodston on Sundays when the rector could not be

present. “He is happy to take Sunday services for as long as

necessary, so we are free to pursue our scheme for Bath.”

“Delightful! How soon can we leave?”

“As soon as you can pack your trunks. Matthew is

readying the curricle, but I shall procure a chaise to carry us and

our luggage.”

Catherine bent to scoop the little terrier into

her lap. “May I bring Ruby Begonia?”

“She will be happier here in the country, I

think, where there are squirrels and rabbits to chase, but

MacGuffin would enjoy a visit to Bath. The waters might do him

good; he is looking a trifle gouty lately, do not you think?”

“By all means let us bring MacGuffin. Dove says

that he pines when you go away without him. Have my trunks sent up

to my dressing-room, and I shall begin packing directly.” With the

assistance of Mrs. Dove, the housekeeper, Catherine’s new

wedding-clothes were wrapped in tissue and folded into the trunks,

and the chaise, loaded with their luggage and a sleepy Newfoundland

dog, was ready to carry them to Bath the following morning. Matthew

had left at dawn, driving Henry’s curricle, and would be in Bath to

receive them.

A pair of pistols, primed and loaded, hung

inside the chaise where Henry could easily reach them. The presence

of these firearms did not unsettle Catherine in the least; indeed,

she experienced a private shiver of delight over the idea of being

waylaid by highwaymen. Fortunately for Henry, who had no share in

that particular species of delight, the journey was uneventful, and

they entered Bath early in the afternoon.

Catherine found the sights, sounds, and smells

of the city as overwhelming and delightful as they had been the

first time she had entered Bath, and she looked about her with an

eager smile, trying to take it all in. Henry watched her with a

smile of his own, finding new delights in Bath as seen through his

beloved’s eyes. Even MacGuffin caught their excitement and heaved

himself to his feet, from which height he could see through the

side glasses of the chaise as easily as his master and

mistress.

Matthew awaited them at a coaching-inn near the

Abbey courtyard, and they were quickly established in a private

room. After refreshing himself with hot tea and sandwiches, Henry

set out to secure lodgings, and by nightfall the Tilneys were in

possession of first-floor lodgings in one of the stately houses of

Pulteney-street. The large sitting-room looked down over the street

and the wide pavements; there was another room comfortably fitted

out as a dining parlor, and a bedchamber with a view over Bathwick.

There was a dressing room for each of them, and the maidservant was

already unpacking Catherine’s trunk and looking askance at the

Newfoundland, who took a quietly polite interest in the

proceedings.

“Come away from there, Mac,” said Catherine. “Do

not drool on my gowns. Come and lie here on your blanket, there’s a

good lad.” She managed to coax him away from the trunks with the

help of a good fire in the sitting-room, before which the

Newfoundland settled himself peacefully.

“There is a ball at the Lower Rooms tomorrow,”

said Henry, who was reading the paper. “I suppose you must visit

all the shops before we make our appearance.”

“Oh, no, not all the shops; Papa was so generous

with my wedding-clothes that I have plenty to wear.”

Despite such sartorial riches, Catherine did

find herself in need of a few indispensible items the next day; and

Henry, all good nature, escorted her to Bond-street and

Milsom-street, where the best shops in Bath were located.

Catherine noticed Henry look up at the windows

of the lodgings he had engaged for his family the previous winter.

His expression was inscrutable; he was not a man to brood, but

Catherine sensed that Henry’s relationship with General Tilney had

none of the easy affection of hers with Mr. Morland.

“Would you have preferred to take lodgings here

on Milsom-street?” she asked him.

“No, my sweet; my taste runs to the newer parts

of Bath. I would have preferred to take lodgings on Pulteney-street

last year, but General Tilney particularly wanted Milsom-street.

Have you everything you need? The time for your public debut of the

season approaches.”

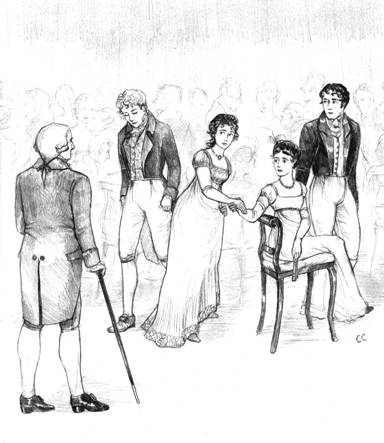

They arrived at the Lower Rooms as the minuets

were ending. The season was full, and the crowd ringing the dance

floor numerous; the last couple retired, and the throng pushed onto

the dance floor, forming sets for the country dances to follow. As

Henry guided Catherine expertly through the mob, the ebb and flow

of humanity brought them suddenly face-to-face with the master of

the ceremonies.

“Mr. Tilney!” he cried. “I am delighted that you

have returned to Bath, sir. And. . . Miss Morland, is it?”

“You see before you the success of your

endeavors, Mr. King,” said Henry. “This is Mrs. Tilney, who was

Miss Morland when you introduced me to her last year. I dare say

you have made a few matches in your time, and here is one more to

add to your list.”

“Indeed I have made a fair few matches,” said

Mr. King, “though my exertions are not entirely directed toward

such permanent arrangements. I felicitate you, Mr. Tilney; and give

you joy, madam. Pray forgive me, but I must give directions to the

musicians. The country dances will begin momentarily.”

Henry took Catherine’s hand and led her to one

of the sets that were forming. Mr. King announced that the dance

would be “Haste to the Wedding,” and the dancers swept into motion

as the music began.

“A fitting choice,” said Henry. “This is our

first dance as a married couple, Cat. We are proof of the parallel

between marriage and a country dance. From the vantage point of

being an old married man of nearly two months, I flatter myself

that the metaphor holds up admirably. Here we are, at the Lower

Rooms, surrounded by other ladies and gentlemen but with no other

thought than to dance together—at least for the first two

dances.”

“Just remember, if you dance with any other

ladies here tonight, that you are married to me.”

“I am not likely to forget, my sweet, for a

hundred reasons.”

Catherine made the agreeable discovery that

dancing with Henry had not lost its charm, and that two dances with

him as her partner passed as quickly as they had the previous

winter—in other words, all too quickly.

As the musicians finished with a flourish, Mr.

King appeared at Catherine’s elbow in the mysterious way that

belonged to truly accomplished masters of the ceremonies, and to

her surprise asked her to lead the next two dances. “It is a

bride’s right,” he told her, “and I hope not a disagreeable duty,

as I have taken pains to procure for you a partner whom you already

know.”

The only young man amongst Catherine’s

acquaintance who might be in Bath was John Thorpe; and it was with

a sinking feeling that she agreed to lead the dance, thinking it a

very onerous duty indeed; but then she realized that Mr. King was

looking expectantly at the young man standing beside him, who was

smiling at her in a very familiar manner, though she did not know

him at all.

Henry’s voice came from behind her. “Mr. King,

your scruples are very kind indeed; but I am afraid that Mrs.

Tilney is not yet acquainted with my brother-in-law. Do not trouble

yourself, sir, for it is the work of a moment. Catherine, may I

present Eleanor’s husband, Lord Whiting?”

Mr. King was all apologies; but Catherine’s real

delight at meeting Eleanor’s husband, and the Viscount’s own good

breeding and charming manners soon did away with all the discomfort

of the moment, and Mr. King soon bustled off to inform the

musicians of Mrs. Tilney’s choices.

“Eleanor’s over that way,” said his lordship to

Henry, nodding towards the chairs. “Sitting out this dance, and I

have been strictly charged to send you to her.”

“Yes, of course,” said Henry, his eyes already

eagerly scanning the chairs. “You are in good hands, my sweet;

enjoy your moment in the sun. I will watch with Eleanor.”

“Give her my love,” said Catherine, “and tell

her that I shall come to see her directly the set is finished.”

Henry immediately disappeared into the crowd,

and his lordship gave Catherine his hand to the top of the set,

where Mr. King stood waiting. “Mrs. Tilney has chosen ‘Mrs. Darcy’s

Favorite,’” he informed the other dancers, and Catherine blushed at

the attention, kind though it was, turned upon her.

Lord Whiting turned out to be an excellent

dancer, perhaps even better than Henry, though Catherine would

scarcely have credited such a notion. The demands of leading the

dance precluded conversation until they reached the bottom and had

a turn out. His lordship said, “You will forgive me if I am too

familiar, Mrs. Tilney; I have heard so much about you from Eleanor

and from Henry’s letters, that I feel as though we are already very

well-acquainted.”

“And I have heard much about you, sir; Eleanor’s

happiness is clear in her letters. I am surprised to learn that you

have come to Bath, though.”

“It was an unexpected trip and arranged with

great haste, as was your own, I apprehend. We arrived only

today.”

“You are not unwell, sir? But I suppose you

would scarcely be dancing if you were gouty.”

“No, I am very well, I thank you; and you are

correct, madam. Considering that most visitors to Bath claim to be

here for their health, it really is astonishing how many of them

turn up at the rooms when there is a ball.”

Catherine assented, thinking his lordship quite

a clever young man; and as another couple had reached the bottom of

the set, they rejoined the dance and had no more opportunity to

speak except for the usual commonplaces of a ballroom until their

two dances were over.

The viscount led Catherine to the chairs; Henry,

taller than those around him, saw her before she reached the chairs

and moved as if to intercept her, but when Catherine saw Eleanor

seated nearby, she ran past Henry to bestow a warm embrace upon

her.

Eleanor returned the embrace, but she looked

past Catherine with an expression of apprehension, an expression

that Henry, who now stood beside Eleanor’s chair, shared; an

expression that Catherine had seen before on both brother and

sister.

She took a deep breath, tried to ignore the

sudden nervous patter of her heart, and turned to make her curtsy

to General Tilney.