There Must Be Murder (6 page)

Read There Must Be Murder Online

Authors: Margaret C. Sullivan

Tags: #jane austen, #northanger abbey, #austen sequel, #girlebooks

“Until tonight, then.” He bobbed a sort of bow

at Catherine and hurried back towards the shop.

As they walked back to Laura-place, Miss

Beauclerk seemed inclined to be quiet, and Catherine allowed her to

be so. Finally she said, “Mrs. Tilney, I must ask you a favor; on

such a short acquaintance as ours, I have no right; but I pray you

will not mention this to my mother.”

“Yes, I suppose she might worry if she knew

about your tonic.”

Miss Beauclerk looked her surprise. “She knows

about my tonic, and what it contains. She uses something similar

herself. It was due to her influence that I asked Mr. Shaw to

provide it. Mother has her own supplier. But I meant meeting Mr.

Shaw. She does not quite approve of my seeing him. I did not intend

to—but it is too late for that. I pray you will not mention

it.”

Catherine promised that she would not as they

entered Laura-place.

“Will you come in for a moment?” asked Miss

Beauclerk. “You may take leave of Mamma, and let her know that I

have not been wandering the streets of Bath alone, and getting into

mischief.”

Catherine thought her request rather

extraordinary, but did not know how to refuse it.

They arrived at the door of Lady Beauclerk’s

house at the same time that a dowdy chaise, drawn by a pair of

shaggy horses, drew up. An elderly servant in well-worn livery

climbed down heavily from his perch and, seeing Miss Beauclerk

staring at him, waved and grinned toothlessly.

“Oh, Lord,” said Miss Beauclerk under her

breath.

Catherine looked at the servant curiously. “Who

is that?”

“He is my aunt Findlay’s man. Well, Mrs. Tilney,

it seems that you will have the opportunity to meet one of the more

eccentric members of my family, arrived with her usual fortunate

timing just as we thought to pass ourselves off creditably in

Bath.”

Catherine, unsure how to respond, said, “I have

a great-aunt who likes to read me lectures.”

“Then you understand what it means to have a

relative whose main purpose in life is to mortify one.”

The servant opened the chaise door and let down

the steps, and his mistress emerged: a woman tall and solidly

built, with a great beak of a nose and a long chin to match. She

looked up at the house and said, “Of course she took one of the

grandest houses in Bath. Such unwonted extravagance! But that is

your mother all over, Judith. What my poor brother would have

thought of it, I am sure I do not know.”

“Good day, aunt,” said Miss Beauclerk.

“Good day, indeed! Do not think I have not heard

what you all have been up to, aye, and that ne’er-do-well nephew of

mine, too. I have my informants, miss.”

“I am sure you do, aunt.” Seeing how Mrs.

Findlay stared at Catherine, she added, “May I present Mrs. Tilney

to your notice?”

“Tilney, eh? I have heard that name, oh yes

indeed. I know what your set is up to.” Mrs. Findlay swept past

both ladies and the footman who held the door. “I trust I need not

send up my card; I trust the dowager will see her poor widowed

sister.”

“Oh, dear,” whispered Miss Beauclerk. “Mamma

will not like it if my aunt insists on calling her ‘the

dowager.’”

“Perhaps I should just go back to our lodgings,”

said Catherine.

“No, no; Mamma will take it amiss if you do not

come up, just for a moment. Pray do, ma’am.”

Catherine could not resist a supplication made

with such softly pleading eyes; and she was herself interested in

seeing her ladyship’s reaction to being called “the dowager.”

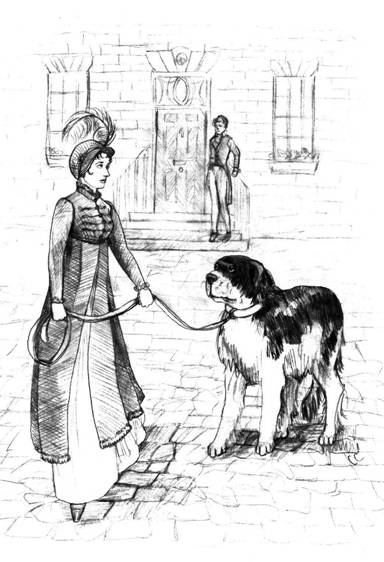

The footman said to her, “Begging your pardon,

ma’am, but your dog looks like he could use a drink of water. I can

take him to the kitchen if you like.”

Catherine looked at MacGuffin’s hanging tongue

and agreed, and the Newfoundland padded down the hall behind the

footman as the ladies climbed the stairs to her ladyship’s

sitting-room.

Sir Philip was there, paying his daily duty call

upon his aunt; he acknowledged Catherine with a nod and a smile,

which she returned, still grateful for his kindness of the previous

evening.

Mrs. Findlay was berating her sister-in-law. “It

had to be Laura-place, did it not, Agatha? No Queen-squares for

you, ma’am! And my poor brother not cold in his grave. ’Tis not

enough that one of you disposed with him, but you must revel in it

by making merry with his fortune!”

“I am sure that I do not know what you are

talking about, Fanny,” said her ladyship; though her blush did not

escape Catherine’s sharp eye.

“I believe you do, Agatha; I know one of you

does. You,” she said, looking at Sir Philip, “or you,” turning a

glare upon her niece.

“What are you suggesting, madam?” asked Sir

Philip, his voice low and dangerous.

“I suggest nothing, sir; I state it for all to

hear. I am come to Bath to determine which of you murdered my

brother.”

Murder and Everything of the Kind

Mrs. Findlay’s words shocked all present into

silence.

“Really, Fanny,” said Lady Beauclerk in a faint

tone of voice. “You must be reading horrid novels to imagine such a

thing. Poor Sir Arthur, murdered! After he suffered so! I am sure

that no man could have been more tenderly nursed by his wife and

daughter.”

“Giving you the perfect opportunity to assist

his exit from this world. And you,” said Mrs. Findlay, rounding on

Sir Philip, “always hanging around and ingratiating yourself with

the old man. You did not think he would hear about your unsavory

adventures, did you? You are fortunate he did not cut you out of

the will!”

“Beaumont is entailed,” said Sir Philip.

“Whatever my uncle thought of me—and I think, and hope, he thought

well—he did not have the power to disinherit me.”

“From the title and the estate, perhaps not; but

what of the funded monies? I know of a few provisions in the

entailment that would have put you in a very uncomfortable

situation indeed: master of a great estate, and unable to afford to

run it!”

“There was no reason for my uncle to change the

provisions of his will,” said Sir Philip with a touch of

impatience.

“No reason? After the way you carried on in

Brighton last summer? To think I would live to see a Beauclerk

involved in a criminal conversation!”

Catherine was paying little attention to the

argument between Sir Philip and his aunt. She was thinking over

everything she had learned that afternoon: that Sir Arthur’s sister

thought his death had not been natural; that both Lady Beauclerk

and her daughter had private, secret access to strong poison; and

that the apothecary who provided Miss Beauclerk with that poisonous

potion had tended Sir Arthur in his last days. A younger Catherine

might have reached a most alarming conclusion indeed; but as Henry

had once bid her, she now consulted her own sense of the probable.

It did not seem possible that a man such as Sir Arthur Beauclerk,

tended by a retinue of servants and physicians, could be the victim

of a murderous plot; but the Beauclerks were an unhappy family, and

who could tell to what measures the desperate might resort?

Sir Philip, mistaking Catherine’s thoughtfulness

for distress, or perhaps just embarrassed that an outsider was

witnessing the incident, said, “Mrs. Tilney should not have to

listen to this.”

Mrs. Findlay whirled about. “Tilney! I have

heard that name. You may tell General Tilney, madam, that he is in

my sights as well. Sniffing round the widow before my poor brother

had been dead half a year! I dare say that fancy Abbey of his costs

a pretty penny to run. He’ll have a mind to your jointure, Agatha,

you may depend upon it.”

“That is enough, aunt,” said Sir Philip. He

crossed the room to where Catherine stood and took her elbow. “Let

me procure a chair to take you home, ma’am.”

“Yes, let Philip help you,” said Miss Beauclerk.

“Thank you for coming out with me this morning, Mrs. Tilney, and I

hope to see you tonight at the theatre.”

Catherine hastily took her leave; Sir Philip

escorted her down the stairs and waited with her while the footman

went off to fetch MacGuffin.

“May I get you a chair?”

“Oh, no; my lodgings are just a few steps away,

and I have my dog.”

“One of the footmen could bring your dog to your

lodgings, and you are distressed by my aunt Findlay’s nonsense.

Pray let me procure you a chair.”

“Oh, I am not distressed,” said Catherine.

He looked at her closely. “Are you not?”

“No, sir; I am perfectly able to walk; but is

very kind of you to think of it.”

“Most women would have a fit of the vapors at

overhearing such an extraordinary declaration as my aunt’s. I

salute you, Mrs. Tilney.”

Catherine smiled and blushed as the footman

returned, leading MacGuffin.

Sir Philip looked at the Newfoundland and said,

“Good Lord. No, you need no chair, Mrs. Tilney; you could ride this

fellow home.”

Catherine considered this. “Henry talks of

training him to pull a little cart to give rides to the children of

our parish. But that would not do for me.”

Sir Philip smiled. “Indeed not, madam; though he

is a handsome lad.” He bent to pet MacGuffin, but the dog pressed

against Catherine and made a sound somewhere between a snort and a

growl.

“For shame, Mac!” cried Catherine. “Sir Philip

means me no harm.” MacGuffin looked up at her with sorrowful eyes.

To Sir Philip she said, “He really is a very good-natured creature

in general.”

“He probably caught a scent of Lady Josephine

upon me. That deuced creature will get my coat all over hair when I

call upon my aunt.”

“Yes, that must be the case. Good day, Sir

Philip, and thank you again for your kindness.”

“It was my pleasure, ma’am. Did I hear my cousin

say that you would be at the theatre tonight?”

“Yes, Lord Whiting procured a box and invited us

to join him.”

“May I look forward to the pleasure of visiting

your box between acts?”

Catherine was unsure of the proper response to

such a proposal. “Why—yes, I dare say his lordship will not

mind.”

“That is very good of you to say.” He raised her

gloved hand to his lips. “Until tonight.”

Catherine, blushing at such attention, hastily

said good-bye and left the house. As she reached Pulteney-street,

she could not help looking back; Sir Philip still stood in the

doorway of his aunt’s house, watching after her with a little

smile.