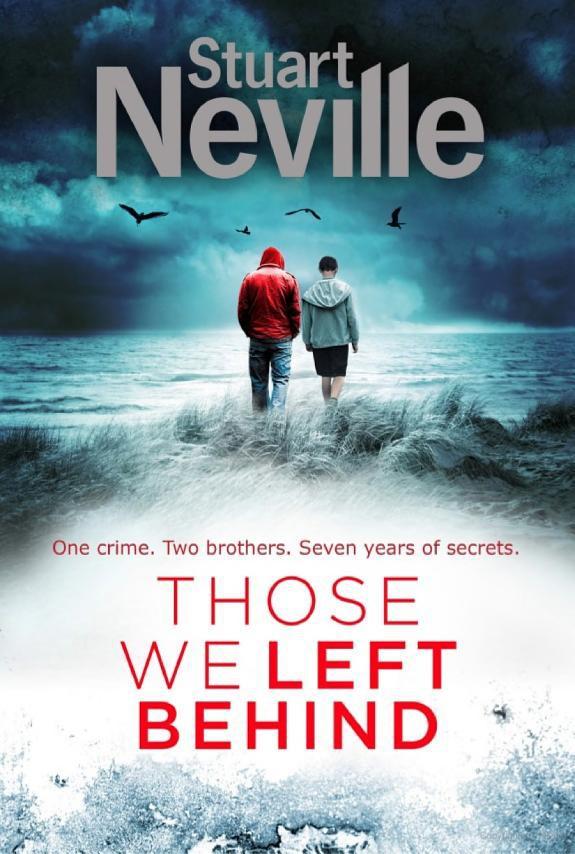

Those We Left Behind

Read Those We Left Behind Online

Authors: Stuart Neville

Contents

When 12-year-old Ciaran Devine confessed to murdering his foster father it sent shock waves through the nation.

DCI Serena Flanagan, then an ambitious Detective Sergeant, took Ciaran’s confession after days spent earning his trust. He hasn’t forgotten the kindness she showed him – in fact, she hasn’t left his thoughts in the seven years he’s been locked away.

Probation officer Paula Cunningham, now tasked with helping Ciaran re-enter society, suspects there was more to this case than the police uncovered. Ciaran’s confession saved his brother Thomas from a far lengthier sentence, and Cunningham can see the unnatural hold Thomas still has over his vulnerable younger brother.

When she brings her fears to DCI Flanagan, fresh back at work after treatment for breast cancer, the years of lies begin to unravel, setting a deadly chain of events in motion.

Stuart Neville’s first novel,

The Twelve

, was one of the most critically acclaimed crime debuts of recent years, winning the Los Angeles Times Book Prize for best thriller.

Collusion, Stolen Souls, Ratlines

(shortlisted for the CWA Ian Fleming Steel Dagger) and

The Final Silence

have garnered widespread praise, confirming his position as one of the most exciting crime authors writing today.

The Twelve

Collusion

Ratlines

Stolen Souls

The Final Silence

For the agents, editors, publicists and many more passionate book people who help create the illusion that I know what I’m doing. I’d be lost without you.

Stuart Neville

THE PILLOW IS

cool on Ciaran’s cheek, damp from sweat. Sunlight makes a glowing rectangle on the wall. It lingers flickery green behind his eyelids when he blinks.

He does not want to look at the wall on the other side of the room, or what lies in the corner there, beneath the window. He does not want to see that. After all the shouting and the noise and the cracking and the hot and the wet, he doesn’t ever want to look at it again.

The mattress rocks. Warm air finds the tiny hairs on the back of Ciaran’s neck and waves them like the grass on the dunes, back when they were little, and things weren’t so hard and angry. A bare arm slips around his waist, the hand taking his. The chest against his back, all warm and cuddly, bony knees tucked behind his.

Ciaran sees the red points of blood on both their wrists. Join the dots. Make a picture.

His hands are sticky with it.

‘Are we going to jail?’ he asks.

‘Probably.’

Thomas squeezes him tighter, his mouth close to Ciaran’s ear. The teeth held behind his lips for now.

‘Will they send us to the same jail? Or different ones?’

Thomas holds his breath as he thinks. After a while, he says, ‘Dunno.’

Ciaran feels something cold and heavy where his heart should be. ‘If it’s different ones, will they let us visit each other?’

‘Dunno.’

‘I hope they do.’

Downstairs, a hammering on the door. More noise when all Ciaran wants is soft quiet. The letterbox squeaks open.

‘Jenny? Jenny!’

Ciaran thinks it’s the old man from next door, the grey one who looks cross and small-eyed at the brothers when he sees them over the hedge.

‘Jenny? David? Are you there? Can you hear me?’

Thomas’s chin rests on Ciaran’s shoulder.

‘David? David! I’ve called the police. Come and open the door if you’re there.’

Far away, high above everything, a wailing noise, rising and falling. Like some terrible animal galloping to their hiding place to gobble them up. It gets louder.

Ciaran wants to cry. He wants to take it back. He wishes it hadn’t happened at all. His shoulders judder as the tears come. He closes his eyes.

‘Shush.’ Thomas’s lips are soft against his ear. ‘We’ll be all right. I’ll look after us. Don’t worry.’

The wailing comes close, falls and dies, the sound of tyres on the driveway outside. Car doors opening and closing.

Ciaran opens his eyes, sees the blue light dancing on the wall.

‘They’re here,’ he says.

He doesn’t know if Thomas hears him. His brother keeps on talking, his words dripping into Ciaran’s ear like warm oil even as the front door rattles on its hinges.

WHEN PAULA CUNNINGHAM

heard the news about the boy’s release, she knew the case would fall to her. She had felt no surprise when Edward Hughes called her to his office. The file had been waiting for her on the boss’s desk, half an inch of reports, assessments and evaluations. It pulled a bitter curse from her throat.

City centre traffic hummed and rattled beneath Hughes’s window, car horns sounding, someone whistling for a taxi. She turned the pages while Hughes chewed a pen at the other side of the desk.

A single photograph of Ciaran Devine at the front, hollow eyes and blank face, a little boy long gone.

They’d used the same picture in the Sunday red top she’d read at the weekend. SCHOOLBOY KILLER TO BE RELEASED, the headline had screamed above a half-page story.

She knew as soon as she saw it. Just knew.

‘Any way out of this?’ she asked.

Hughes shook his head. ‘None at all. The young fella needs your experience.’

‘What about Terry Grimes?’

‘Terry’s tied up. It’s your case, and that’s all there is to it. You can handle him. He’s been good as gold on his temporary releases. Tom Wheatley at the hostel says he was no bother at all when he stayed over.’

The boy would have had excursions accompanied by one of his case managers. Shopping trips, a meal at McDonald’s, a walk in the park. Finally, they would have allowed him a night in the hostel off the Saintfield Road, in the south of the city.

She pictured him sitting in the small, clean room, perhaps counting coins in the palm of his hand, trying to grasp the simple acts other people took for granted. Going to a shop counter, asking for what he wanted, saying please and thank you.

Cunningham remembered taking a lifer called Brian to a newsagent’s. He had mumbled, ‘Polo mints, please.’ The shopkeeper had set the sweets on the counter. Brian, who had strangled his girlfriend to death after a drinking binge, had grabbed the packet, dropped a twenty-pound note in its place, and walked out of the shop.

When she’d caught up with him, his change in her hand, Cunningham asked why.

Brian had stood there on the pavement, blinking tears from his eyes, before he said, ‘Cause I don’t know what they cost.’

Remove a man from the world for years then drop him back into it, expecting him to simply pick up where he left off. It doesn’t work. He’ll be lost. And Ciaran Devine would be no different.

Cunningham had entered the Probation Service twelve years ago, not long after gaining her MSc in clinical psychology. As a postgraduate student, she had spent summers working on the wards of psychiatric units, then a year in Maghaberry prison, counselling inmates. She had learned things in those days that would stay with her until her last breath, like the terrible cost of casual violence, and how poorly the system dealt with those who inflicted it.

In all those dozen years, Cunningham wasn’t sure if she’d ever done any good.

She let the air out of her lungs, wished for a cigarette. ‘All right,’ she said. ‘When’s the ADR?’

‘He gets out Wednesday. That gives you a week to prepare.’

‘Jesus, how am I supposed to prepare for this?’

Hughes put his forearms on the desk. ‘In a thorough, diligent and professional manner.’

Cunningham glanced at him over the open file. He probably thought he was giving her his serious face, but he looked more like a prissy matron. Edward Hughes was on the large side, yet he had a countenance more like that of a schoolboy than a man well into middle age.

‘What about the brother?’ Cunningham asked.

‘Thomas? He’s kept out of trouble since his release. He’s not supervised any more.’

The newspaper had also carried a picture of Thomas Devine, smaller than that of Ciaran, tucked away on the second page. Older, leaner, darker. Handsome like his brother, but in a sharper, more jagged way.

An image flashed in her mind: the boys escorted towards the side entrance of the courthouse, blankets over their heads, a uniformed policeman at each arm, followed by the detectives who got the confession, brilliant camera flashes, screams of hatred from the onlookers.

No one knew the boys’ names then, the press ordered to keep quiet.

‘He didn’t go for a Mary Bell order?’ Cunningham asked.

A new identity, a lifetime of secrets, named after a little English girl who did two unspeakable things almost half a century before.

‘Thomas gave it a go,’ Hughes said. ‘The judge threw it out. He didn’t reckon they were under sufficient threat.’

The names had appeared in the papers more than a year and a half ago when Ciaran had turned eighteen. His minimum tariff of six years had expired, but he continued to be held at the Secretary of State’s pleasure. The local Belfast journalists salivated over a potential release, stored up their bile and outrage. Politicians gave stiff-lipped opinions that amounted to nothing.

‘God help him,’ Cunningham whispered.

She hadn’t meant to say it out loud. She glanced up at Hughes, expecting a reproach.

He said, ‘God help the both of you.’

DETECTIVE CHIEF INSPECTOR

Serena Flanagan punched in her key code and entered the station’s core. A walled compound containing a cluster of red-brick buildings, small windows, a fortress in the heart of Lisburn, built to shield its occupants from bullets and bombs. Flanagan avoided all stares, averted her eyes as she made her way to the second floor and the office she hadn’t seen in four months. Whispers followed her through the corridors and stairwells.

‘Ma’am,’ a voice called.

Flanagan pretended she hadn’t heard it, kept walking, her door only a few yards away now.

‘Ma’am.’

She stopped, gave a silent curse, and turned.

Detective Inspector John Hoey, a coffee in one hand, a sheaf of papers in the other. Flanagan offered a smile, a nod.

‘Good to see you back,’ he said as he approached. ‘How are you feeling?’

‘Not bad,’ she said. ‘Looking forward to getting to work.’

‘I see your hair grew back.’

Flanagan had turned to leave, but his words stopped her. ‘Excuse me?’

‘From your treatment.’ He raised his coffee cup, pointing a finger at her head. His face dropped. ‘Oh. Is it a wig?’

Flanagan took a breath. Gave him a patient smile. ‘I didn’t have chemotherapy,’ she said. ‘Just radiotherapy. So I didn’t lose my hair.’

‘Oh,’ he said. ‘Oh, good. I was wondering, will you be getting your team back together?’

‘Yes,’ she said. ‘As soon as I get caught up, see who’s still available.’

‘I’d like to be considered,’ Hoey said. ‘Just so you know. If you need the numbers made up.’

‘I’ll bear it in mind,’ she said. ‘Thanks.’

Flanagan turned, left him there, and headed for her office. She let herself in, closed the door behind her, leaned her back against it.

Aside from Hoey’s crass stupidity, she thought, that wasn’t so bad. She’d been dreading the return for weeks. The looks of pity. The expressions of sympathy. They would come, that much was certain, but she felt that perhaps she could at least be gracious in response.

Six weeks after her surgery, she had been in Tesco browsing loaves of bread. She had nudged her trolley against another shopper, turned to apologise, and recognised a work colleague of her husband’s. Heather Foyle, she was called, a maths teacher.

Heather had stared at Flanagan, eyes and mouth agape, visibly struggling to find a few words.

‘For Christ’s sake, I didn’t die,’ Flanagan said before wheeling her trolley to the checkouts, her face burning, regret already souring her stomach.

She had called Heather later that evening to apologise, battled through the no-don’t-mention-its, tried to explain herself against the tide of condescension. Even then, when she knew she was entirely in the wrong, aware that Heather Foyle was simply being a good person, Flanagan had to stamp on her own anger. She had never experienced the pity of others until her breast cancer diagnosis, and it was more unpalatable than she had ever imagined.

So far, only Hoey, his clumsy words and his expedient sympathy as he fished for opportunities. She could take that. There would be more to come, and she would smile and say, I’m fine, thank you, and ask after the enquirer’s wellbeing, and most definitely not shout at him or her to shut up, just leave her alone, let her get on with living.

Flanagan’s office remained as dim as she remembered, sunlight muted by the tinted glass in a window so small it served little purpose. And hot, too. She crossed the room, opened the window to its full extent, which was no more than a couple of inches. For her own protection, her superiors would have said. This building looked like a small prison from the outside, and often felt like one within. Across the rooftops, she could just see the spires of Christ Church. Flanagan counted herself lucky; most of the views from this station were of walls and wire fences.

She took off her jacket, slung it over the back of her chair, and sat down. The quiet of the room seemed to press on her, a physical sensation, as if the silence hardened the air.

Three framed photographs sat on her desk, one portrait of each of her children, and another picture of the family. One of those terrible posed studio shots that she disliked, but Alistair had insisted. She’d turned the frames face down the last time she left the office. To keep the dust off them, she’d told herself, but part of her believed it was to shield her family from the goings-on here.

Flanagan set each of them upright and was startled by how young Ruth and Eli looked, how much they had changed, and she felt a strange sadness for the smaller children they’d left behind in these images.

A sharp rap of knuckle on wood made her jump. She exhaled and said, ‘Come.’

Detective Superintendent Stephen Purdy opened the door. A stocky bespectacled man with a shock of pure black hair that some speculated was a wig. Flanagan had inspected it as closely as she could and found no evidence to back up the claim, though she suspected he dyed it.

‘It’s good to see you back,’ he said. ‘How are you feeling?’

‘I’m fine, sir, thank you,’ she said, hoping he wouldn’t ask her to elaborate.

DSI Stephen Purdy was not an idiot like Hoey. He lacked emotional intelligence, found casual conversation difficult, but he was not stupid. He would know not to push her on her illness.

‘Good, good,’ he said.

She indicated the seat in front of her desk as she sat down.

‘No, I’m not stopping.’ He hovered there, looking as comfortable as a mouse in a cattery.

It was up to Flanagan to set him free. ‘What can I do for you?’

‘Ah, well, first of all I wanted to welcome you back.’ He dipped his head and waved a hand in a bowing gesture. ‘And to get you started on some work.’

Flanagan had noticed the file under Purdy’s arm when he entered her office. He placed the manila folder on the desk and tapped it with his index finger.

‘This was sent over from B District. You know DCI Thompson’s retiring in a few weeks? He’s leaving a lot of unfinished business behind him. Between you and me, his MIT had become a bit of a shambles. These are the loose ends from the last few cases he’s left open. The ACC wants you to work through them, see what’s still worth following up, what’s better off dropped, that kind of thing. He thought it might keep you occupied while you get settled in again. I can let you have a few DCs if you need the help. There’s a new DS, Ballantine, she’s very capable. Now that Calvin’s abandoned us, she might make a good starting point for a team.’

Detective Sergeant Calvin had been Flanagan’s assistant on her Major Investigation Team. He’d suffered a shoulder wound before she had taken leave for her surgery, and that had been enough for him. The Police Federation had helped him push for a medical pension, and then he was off.

‘I don’t imagine she’ll want to start off pushing paper around for you,’ Purdy said, ‘but we all have to do it sometimes.’

Flanagan felt a growing weight inside. A file full of busywork and drudgery, sweeping up someone else’s mess.

Purdy saw the disappointment on her. ‘Come on,’ he said. ‘You’ve been out of action for weeks. You can’t expect just to land back here and dive into a hot case. It’ll be a month or more until you’ve got a proper team established again. I can’t have you twiddling your thumbs for all that time.’

She waved at the file. ‘I know, but this . . .’

Purdy gave her his sternest look, usually reserved for the lower ranks. ‘It’s not exciting work, I know, but there are victims in those pages that still need someone to speak for them.’

‘Of course,’ Flanagan said, feeling like an admonished child. ‘You’re right. I’ll get working.’

Purdy nodded and said, ‘I’ll leave you to it.’ He stopped at the door. ‘Oh, I meant to say. You heard about the Devine boy?’

‘That he’s due for release, yes.’

‘Wednesday,’ Purdy said.

‘That soon?’

‘I’m not supposed to know that. They’re keeping it quiet to stop the press going after him. A call came in last week from the probation officer who’s been assigned to him. She wants a word with you. I told her to come by today, late morning. All right?’

She remembered Ciaran Devine, a child then, a young man now. A little over seven years ago, the first awkward signs of puberty about him, sitting across the table from her in an interview room. She was the only one he talked to. He called her by her first name. Even when he confessed, she struggled to picture this small boy doing that terrible thing.

She had voiced her doubts, but the boy had confessed, and that was enough.

Ciaran had sent her a letter after his and his brother’s convictions. It came via the station. She had blushed when she read it. It still lay at the back of a drawer in her bedroom at home, even though she should have destroyed it.

‘All right,’ Flanagan said.

‘Good. Here’s hoping he stays out of trouble.’

As Purdy left the room, closing the door behind him, Flanagan pictured Ciaran Devine’s thin fingers, the tiny cuts on his skin. She pushed the image from her mind and opened the folder in front of her.

Flanagan met Paula Cunningham in the reception area at twenty-five minutes past eleven. A little less than average height, slim build but not skinny, perhaps a decade younger than Flanagan. Businesslike in her manner.

Stop it, Flanagan told herself. Every new person she met was subject to the same kind of snap judgements, as if they were a suspect in some investigation only she knew about.

She gave Cunningham’s ID a cursory glance, nodded, extended her hand. They shook.

‘Thank you for seeing me,’ Cunningham said. ‘I know you’ve just returned to work. I’m sure you’ve a lot to catch up on.’

‘Surprisingly little,’ Flanagan said. ‘My office okay?’

‘Absolutely.’

They did not speak as Flanagan led Cunningham beyond the locked doors and up to her room. Cunningham took a seat. Flanagan sat opposite.

Cunningham looked up at the window over Flanagan’s shoulder. ‘Doesn’t it get claustrophobic in here? So little light.’

‘You get used to it,’ Flanagan said. ‘So you wanted a chat.’

‘Yes,’ Cunningham said, pulling a notebook and pen from her bag. ‘About Ciaran Devine.’

Moleskine notebook. Parker pen. Good quality, but not flashy. Functional. Plain shoes with a small heel. Not much jewellery, minimal make-up.

Stop it, Flanagan told herself again.

‘What do you want to know?’ Flanagan asked.

Cunningham opened the notebook, readied her pen. ‘I understand you conducted most of the interviews with Ciaran.’

‘That’s right. You should be able to access the transcripts that were submitted by the prosecution.’

‘Yes, I have them. But I wanted your impressions of him. What did you feel about him?’

Flanagan looked away, hoped her discomfort didn’t show. She examined the back of her left hand. Her wedding and engagement rings. The small scar from when, as a child, she’d tried to crawl beneath barbed wire into the field behind her grandfather’s house to see the pony with the sagging belly and matted coat.

‘Well, my first impression,’ Flanagan said. ‘My first impression was the blood on the wall.’