Thought Manipulation: The Use and Abuse of Psychological Trickery (25 page)

Read Thought Manipulation: The Use and Abuse of Psychological Trickery Online

Authors: Sapir Handelman

Tags: #Psychology, #Reference, #Social Sciences, #Abuse & Physical Violence, #Nonfiction, #Education

30. In the language of constitutional economists, the quest is to inquire how the participant “may be able to play better games by adopting superior rules.” (Vanberg, “Market and State,” 27.)

31. Of course, “the social contract problem” has many versions and variants. One of its well-known versions is Immanuel Kant’s formulation of the problem of the republican state (Kant, I., “Perpetual Peace,” in

Classics of Modern Political Theory

, Edited by Steven Cahn, New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, (1795) 1997, 582): “Given a multitude of rational beings who, in a body, require general laws for their own preservation, but each of whom, as individual, is secretly exempt himself from this restraint: how are we to order their affairs and how to establish for them a constitution such that, although their private dispositions may be really antagonistic, they may yet so act as checks upon one another, that is, in their public relations the effect is the same as if they had no such evil sentiments. Such a problem must be capable of solution.” However, so far as I know, Kant only formulated the problem without offering solutions.

32. See, for example, Szasz, T. S.,

The Myth of Psychotherapy: Mental Healing as Religion, Rhetoric, and Repression

(New York: Syracuse University Press, 1988).

CHAPTER 11

Liberation by Manipulation

“Expanding manipulations” aim at expanding the target’s perception of available options. They are constructed to expand the target’s field of vision without direct interference in his final decision. The manipulator is expected to accept and respect any final choice the target makes. I have distinguished between two means to achieve the expansion effect: emotional and intellectual. Emotional manipulations are designed to provoke strong feelings and desires in order to liberate a fixated target. Intellectual manipulations are geared toward convincing the target to examine reality from different perspectives. In intellectual manipulations, arguments and considerations are designed to maneuver the target to discover new horizons.

This chapter presents, analyzes, and evaluates an intellectual manipulative strategy. The liberal manipulator, who intends to help the target to discover new dimensions, constructs and presents a manipulative hypothesis. The manipulative hypothesis seems to be competitive, at least in some respect, to the target’s initial position.

The manipulative hypothesis tactic, as I may dub such strategy, can be very effective in cases where the target seems to be possessed by a closed conviction. The manipulator believes that the target is trapped in a narrow perception of reality, which he is unwilling to examine critically, let alone consider other alternatives. Therefore, it might sound strange and even useless to try to convince him by presenting a competitive alternative while it is clear that he is not willing to listen. However, presenting a competitive alternative in a sophisticated manner might open for the target the possibility to change his attitude.

The “manipulative hypothesis tactic” is built to avoid any direct confrontation with the target about his attitude. The manipulator’s intention is to bypass the defenses that the target is “well-trained” in using for blocking any possibility for critical discussion. The manipulator intends to penetrate doubts in the target’s mind about the practical value of the target’s viewpoint, without confrontation and criticism. To succeed in such difficult mission, the “manipulative hypothesis,” first of all, has to distract the target’s mind from his original outlook. It has to attract his attention and provoke his curiosity. Therefore, the presentation of the hypothesis should contain elements, which often appear in competent works of art: surprise, mystery, tension, drama. These elements intend to prepare the ground for the presentation of a manipulative idea in the maximum persuasive power.

An effective technique to achieve such an effect is suggesting to the target an absurd hypothesis that exceedingly contradicts his outlook. The manipulator indeed suggests an alternative, but the alternative is not practicable for the target. In this way the manipulator makes certain that he does not maneuver the target toward one specific practical option (as in limiting manipulation) but focuses only on expanding horizons. The power of what seems to be an absurd hypothesis can be realized in two dimensions. On the one hand, an absurd idea does not appear seriously threatening. Therefore, the engrossed target might feel safe enough to listen and think about the “strange” ideas. However, whenever the smallest doubt comes to the target’s mind that there might be truth in such an absurd hypothesis, it can shake even what seems to be a solid position.

To illustrate the power of such manipulative technique, I present a masterpiece in the art of manipulation. This fascinating example is enshrined as canonical. However, many “experts” will never accept the idea that this case reflects an intentional manipulative strategy. I do not have any intention of entering into a debate on the intentions of the principal figure. I have no interest in judging whether he intended to manipulate or he believed that his astonishing hypothesis is the naked truth. His thoughts are his own private heritage, and we do not have the ability to objectively test his intentions. Moreover, as I have argued in the beginning of the book, almost every motivating action that intends to influence and convince necessarily contains manipulative elements.

My intention is to demonstrate a manipulative strategy that might be useful in cases of rigidity and inflexibility. It seems to me that familiar and sensational cases can be readily illustrative and persuasive. As I feel obligated, I reiterate with emphasis that any labeling of manipulative intentions here does not express moral judgment. As stated in the very beginning of this book, manipulations range from the most reprehensible vice to sheer altruism.

The example presented here analyzes a well-known interpretation of a short dream. This dream and its interpretation were taken from the highlight of Sigmund Freud’s great work,

The Interpretation of Dreams

. However, it is this short case study that clearly reflects severe doubts on Freud’s revolutionary approach to dreams: Did Freud, the master of interpretation, really interpret dreams or did he develop a manipulative technique to work with dreams for therapeutic application?

CASTING DOUBTS UPON AN ENTRENCHED POSITION

It is quite common for a person to reach out for psychotherapy because of distress. However, many times, there are good reasons to believe that there is an enormous gap between the patient’s hypothesis about her misery and the actual root causes of her misery. Unfortunately, in the more severe cases, the patient conceals a greatest secret connected to her suffering that she is persistently unwilling or, according to Freud, unable to reveal and discuss. Therefore, helping the patient improve her quality of life requires an indirect approach for exposing the secret.

In the previous chapter I explained that a powerful incentive (such as affection for the therapist) might stimulate the patient to talk and reveal her unpleasant secrets. I had explained in detail that a classical Freudian therapist will try to use love and the sexual affections of the patient (transference-love) to expose essential and sensational details from her biography. However, many times those important details, which have direct projection upon the patient’s distress, remain a mystery. The true biographical source of the misery is not always clear, maybe never completely clear, and sometimes it seems impossible even to come close to it. As an alternative for revealing the truth, the authentic source of the misery, the therapeutic interaction focuses on raising doubts in the patient’s mind about her view of central elements in her life. The purpose is to enable her to consider different options in general and the possibility for a change in particular.

This approach leans on the presumption that at the end of the process the patient will be able choose the best available option (according to her preferences) from the range of possibilities at long last appearing before her. Careful study of Freud’s interpretations of dreams is consistent with this way of thinking.

INTERPRETATION OF DREAMS: MANIPULATION OR HIDDEN REALITY

Freud’s interpretation of dreams does not stand in a vacuum. It is strongly relates to his research, theory, and therapy. The impression is that Freud’s main purpose extends beyond amusing himself with solving riddles and puzzles, much as often he might so indulge, but to use dreams for therapeutic application.

A therapeutic implement means nudging an entrenched and stubborn patient in any direction that will make her more flexible to consider a change in her attitude for her life. For this purpose, Freud uses sophisticated hermeneutic tools in order to structure a convincing story. It appears that his interpretations are covertly replete with all the convincing plot elements of a best-seller: tension, drama, intimacy, sex, jealousy, and, of course, a surprising and shocking twist at the end.

It is instructive to follow the way Freud turns the dream’s story, which often seems meaningless and sometimes even complete nonsense, into a brilliant interpretation that will not shame even the best writers. However, the chord, which connects the different fragments and turns them into a brilliant and well-constructed interpretation, does not exist in the dream’s story. The glue that joins different pieces from the dream’s story and turns them into a well-constructed plot is taken from the dreamer’s associations. Therefore, we might wonder again: Did Freud objectively interpreted dreams without ulterior purpose? Or did he construct manipulative hypotheses for therapeutic needs? In any case, whether Freud consciously intended to manipulate or his hypotheses are completely sincere, his work with dreams offers a fascinating study in the construction of expanding manipulations.

LIBERATION OR OPERATION

The following example briefly demonstrates Freud’s method of interpreting dreams. His interpretation, which clearly contains absurd elements, contradicts the dreamer’s perception of an essential part in her personal life. Freud is very cautious about instructing the dreamer in how to deal with his sensational findings. He is mainly satisfied with shocking her by exposing her latent wishes and regrets. Therefore, the interaction, which cast doubts on her view of central elements in her personal life, is colored liberally. However, Freud’s observation is not a subject to negotiation. His views on the dreamer’s wishes and desires are definite, and it does not matter if she likes it or not. Accordingly, whether Freud’s move reflects his “real” observation or it is the outcome of an intentional manipulative strategy, the interaction leaves deep paternalistic impression.

Let me go ahead to present the dream:

“Very well then. A lady who, though she was still young, had been married for many years had the following dream: She was at the theatre with her husband. One side of the stalls was completely empty. Her husband told her that Elist L. and her fiancé had wanted to go too, but had only been able to get bad seats—three for 1 florin 50

kreuzers —and of course they could not take those. She thought it would not really have done any harm if they had.”

Freud’s interpretations combine elements from three main resources: the dream’s story, the dreamer’s associations during the session, and the dreamer’s biography. It is fascinating to follow the way Freud weaves and intertwines an elegant interpretation from those three sources of information. Here, I bring only sensational parts from the interpretation and the interaction.

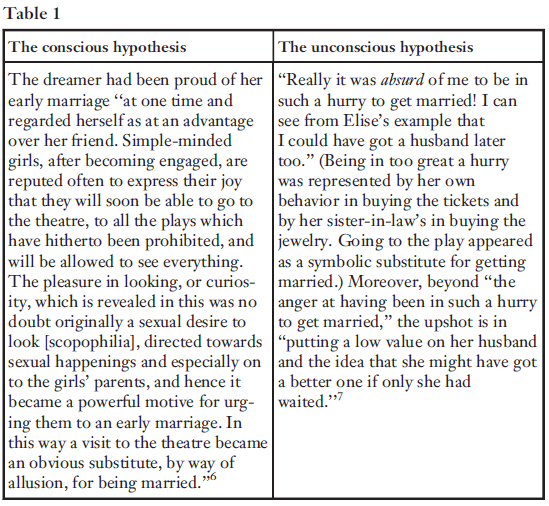

We learn from Freud that one of the most important details is that the dreamer’s husband “had in fact told her that Elise L., who was approximately her contemporary, had just become engaged.” Freud assumes that this piece of information, which is not appearing in the dream’s story, is, actually, the trigger of the dream. In his analysis, Freud stretches this fine plot point in two different directions and suggests two contradictory hypotheses respectively: “the conscious hypothesis” and “the unconscious hypothesis.”

“The conscious hypothesis” points that the dreamer has felt advantage toward her friend (at least in the past) since she has been married. “The unconscious hypothesis” expresses discontents from the haste with which she, the dreamer, had rushed into marriage.

I present the two opposed hypotheses, one against each other, in Table 1:

It is astonishing to observe how Freud is turning the dream’s story on its head. For example, the dreamer’s friend, who seems to be the heroine of the dream’s story, is discovered as a marginal figure in the interpretation. Moreover, it turned out that the dreamer’s friend is only a vehicle for the main issue: the dreamer’s attitude towards her marriage in general and her husband in particular.

Freud marvelously uses a simple, innocent, and perhaps meaningless story of a dream to construct an entire theory. Freud’s theory is discovering to the dreamer (or maybe the patient) a dominant motif in her life that she was not aware of: her ambivalence towards her marriage (the unconscious hypothesis).

Freud concludes that the foundation of the dream is a wish of having postponed her marriage. Of course, this wish is not realistic at least in our world. It is impossible to turn back the clock and reverse past decisions and actions. Therefore, the motivation of the dream, according to Freud, is an absurd wish. The inability to give up on an unrealistic wish, a wish that can never be fulfilled, is probably the reason that it is “buried” deep in the dreamer’s unconscious. Freud’s interpretation is revealing to us, and more important to the dreamer, that she speaks simultaneously in two opposing voices: content and discontent from her married life. This sensational discovery “accidentally” fits well to a Freudian paradigm: unsolved ambivalence is one of the main sources of suffering. Freud’s work in general, and his interpretations of dreams in particular, indicates that our unconscious is able to make extremely complex calculations. For example, the dreamer has creative abilities to compose a sophisticated riddle (the story of the dream) from a simple story of dissatisfaction (unhappy marriage). The inevitable questions that arise are: Do we indeed possess such creative capabilities which we are not aware of? Or is it Freud’s creativity and sophistication that enable him to construct impressive fictions from banal, simple, and maybe unclear pieces of information?