Three Lives: A Biography of Stefan Zweig (14 page)

Read Three Lives: A Biography of Stefan Zweig Online

Authors: Oliver Matuschek

We were always tempted to be jolly, but down there, somewhere in the bowels of the ship, he was fading fast, attended by his wife, and we felt it like a shadow falling across our carefree day. Sometimes, when we laughed, someone would say: “Mahler! Poor Mahler!” and we fell silent. He lay deep down below, a doomed man, burning up with fever, and only a small bright flame of his life flickered on up above on the open deck: his child, playing without a care in the world and blissfully unaware. But we knew: we could feel him down there beneath our feet, as if in the grave.

Zweig’s essay inevitably homes in on the question of whether he, as an observer and chronicler of the times, would get to see the composer in person one more time. And sure enough, when they arrived in Cherbourg, he did get to see him. The shipping company had prepared a bed for Mahler on the tender that ferried the passengers from the transatlantic steamer to the shore. Zweig takes up the story:

He lay there, pale and ashen like a dying man, motionless, with his eyes closed. The wind had blown his grey hair to one side, his domed brow stood out clear and bold, and below it the hard chin, in which the thrusting power of his will resided. His emaciated hands lay folded in weariness on the blanket, it was the first time I had seen him—the fiery genius—brought low. But that silhouette of his—unforgettable, truly unforgettable!—was outlined against a grey infinity of sky and sea, there was such endless sorrow in this spectacle, but also something that transfigured it through greatness, something that faded away, like music, into a sublime other world. I knew that I was seeing him for the last time. Overwhelming emotion drew me towards him, timidity held me back, I had to look at him from afar and keep on looking, as though through the sight of him I could still receive something from him, and be thankful.

12

Caught up in the drama of the moment and intent on sustaining the suspense of his narrative, Zweig apparently failed to notice (or chose not to notice) that his attempts to approach Mahler were not welcomed by everyone. And for obvious reasons he omits to mention in his account why it was that he could only peer at Mahler “from afar”—because the area around his bed had been deliberately shielded from prying eyes by a wall of piled-up suitcases and crates. The overwhelming emotion and timidity that Zweig speaks of were undoubtedly very real, but he was no less moved by his innate curiosity and love of sensation. This is confirmed when we look at everything from the opposite point of view. The fact is that Alma Mahler has also left us an account of this memorable voyage, during which Busoni had told her “that there was a young Austrian on board the ship who let it be known that he would like to offer his services to Mahler and me”. Perhaps she already suspected that the young man,

whose name she does not mention, was trying to get close to Mahler for reasons other than a simple desire to help: “I sent word to him that I did not require any assistance during the crossing, but that I might be glad of his help when we were going ashore.” There can be little doubt as to the identity of the young man when we read on in Alma Mahler’s account: “When we disembarked he was nowhere to be seen, although he was the only one on the tender who had been peering at Mahler over the suitcases, prompting Mahler to turn over so that he would not be seen by him. But we saw him in Cherbourg, in a great hurry to get to the customs office. When I arrived he had just finished. Now he’ll offer to help me, I thought. Not a bit of it! He disappeared, and I found him with Gucki [her daughter Anna], telling her fairy stories in a loud voice. Mahler became agitated, and asked me to request the young man to desist.”

13

Gustav Mahler lived on for just a few more weeks after arriving back in Europe. After his death in May 1911 Zweig added a dedication to the poem

Der Dirigent

, which he had written the year before: “In memoriam Gustav Mahler”. And indeed, memories of Mahler’s concert evenings in Vienna were doubtless in his mind when he wrote these lines. In the poem the maestro steers a boat through the sea of sounds, sustaining the illusion—until the curtain falls, the lights go up, the applause rises to a crescendo and the audience returns from its dream world to the here and now: “We have reached the shore on which all dreams are wrecked.”

14

NOTES

1

Stefan Zweig to Leonhard Adelt, probably early September 1903. In: Briefe I, p 61.

2

Zweig GW Welt von Gestern, p 215.

3

Sehnsucht nach Indien. In: Zweig GW Reisen, p 97 ff.

4

Stefan Zweig to Börries Freiherr von Münchhausen, probably November 1908. In: Briefe I, p 179.

5

Stefan Zweig to Victor Fleischer, 19th December 1908. In: Briefe I, p 181.

6

Gwalior, die indische Residenz. In: Zweig GW Reisen, p 106.

7

Stefan Zweig to Insel Verlag, February 1910, GSA Weimar, 50/3886, 1.

8

Copy in the archive of S Fischer Verlag.

9

Die Stunde zwischen zwei Ozeanen. Der Panamakanal. In: Zweig GW Reisen, p 156 f.

10

Parsifal in New York. In: Zweig GW Reisen, p 144 ff.

11

Matuschek 2005b, No 854.

12

Gustav Mahlers Wiederkehr. In: Zweig GW Zeiten und Schicksale, p 76 ff.

13

Mahler 1971, p 225.

14

Zweig GW Gedichte, p 195 ff.

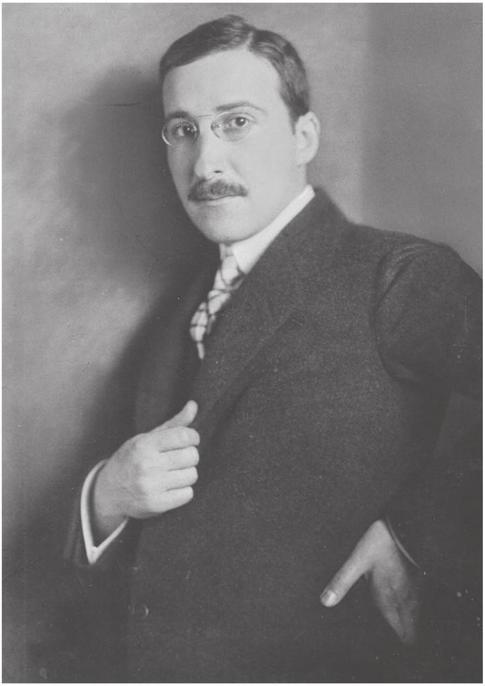

Stefan Zweig circa 1912

Trials and Tribulations of a Writer

The one-time bohemian had turned into an elegant young man

.

1

Friderike on Stefan Zweig, writing in 1912

T

HE USUAL CYCLE OF

work and travel was briefly interrupted following Zweig’s return from America, when he had to check in to the sanatorium of Dr Anton Loew in Vienna to have an operation on his costal pleura. He was quite badly affected, less by the operation than by the after-effects of the anaesthetic, which resulted in sleepless nights. To his chagrin he remained out of sorts for a good month afterwards, but even so he was dictating letters from his sickbed again within a few days. The operation left him with a large scar, which would help him to avoid conscription at subsequent army medical examinations.

After the operation he allowed himself little rest and no time away from home to convalesce. Instead he tried to find the concentration he needed within his own four walls to catch up on his work as quickly as possible. To his amazement he had discovered the year before that the building where he lived in the Kochgasse harboured a surprise that few others, it is fair to say, would have found quite so exciting as he did. During a chance conversation with the woman who lived upstairs from him, who gave piano lessons in her apartment, he found out that she was living there with her mother. And this elderly lady, Ottilie Demelius, was none other than the daughter of Goethe’s personal physician, Dr Vogel. And that was not all: Goethe himself had been her godfather, and had attended her christening. The very thought was almost too much for Zweig:

I felt a little giddy—here was someone still alive in 1910 on whom Goethe’s divine gaze had rested! Now I had always had a special feeling of reverence for every earthly manifestation of the great genius, and as well as [ … ] manuscript pages I also collected every sort of relic I could get my hands on [ … ]. I kept a quill feather used by Goethe under glass for years [ … ]. But how could one compare these inanimate objects with a living, breathing human being, on whom Goethe’s dark, round eyes had once knowingly and affectionately gazed? Through this frail earthly creature a last fragile thread—which could snap at any moment—connected the Olympian world of Weimar with this otherwise insignificant suburban dwelling at Kochgasse 8.

2

On more than one occasion Zweig took tea with Frau Demelius, and he insisted on presenting her, like a living museum piece, to fellow collector of Goetheana Kippenberg during a subsequent visit to Vienna.

These intriguing neighbours, who so appealed to Zweig, had helped him to feel very much at home in the Kochgasse. One entered his apartment through a narrow hallway, lined on both sides with floor-to-ceiling bookcases. The shelving carried on through all the rooms, and there were piles of books, papers, newspapers and files wherever one looked. In the meantime he had begun to augment his already extensive library with numerous catalogues of autograph manuscripts from auction houses and antiquarian booksellers. In the parlour, where the precious manuscript and drawings by Goethe and Blake were displayed on the walls, red-leather armchairs invited Zweig and his guests to sit in comfort and talk over coffee and cigars. When the weather was warmer it was also possible to sit out on the balcony. But for longer sessions the assembled company would nearly always have to decamp to a restaurant or café, since the limited facilities in the apartment only stretched to the preparation of coffee, tea and a “cold bachelor supper”.

3

The kitchen was small anyway, but owing to lack of space it had been converted into an office complete with filing cabinet. Instead of a cook, the room was for many years the domain of a secretary, Mathilde Mandl, whose professional services Zweig shared with his colleague, Siegfried Trebitsch. The work of the office was well organised. For brief acknowledgements there were pre-printed cards with messages such as: “Stefan Zweig (currently away on his travels) is very sorry that on this occasion he is unable to send you a copy of his book in person.”

4

There was a typewriter in the office, but for private correspondence and communications with esteemed colleagues Zweig continued to write his own letters by hand, of course, and nearly always in purple ink. This colour became an instantly recognisable feature of his letters, as did the round, very legible handwriting and the monogrammed letterhead.

The lack of a proper kitchen meant that Zweig normally went out to lunch. If his brother Alfred happened to be in Vienna, they would meet up for lunch nearly every day at their parents’ home, just as they had in

childhood days. The mood at these family gatherings was sometimes rather gloomy—despite the regular sojourns in Marienbad and more recently in Wiesbaden, Ida Zweig was catching colds more often and her husband too was having problems with his health. Both sons were worried and worn down by this state of affairs, because despite their best efforts to persuade them their parents could not bring themselves for a long time to change their (evidently not very helpful) doctor. “All this rushing around in the streets”, wrote Stefan, “and the draughty tramcars and omnibuses are doing more damage to Mama’s health than all the spas in the world could put right. It’s high time something drastic was done, either a carriage or an extended stay in the south.”

5

But here again the Zweigs preferred to duck the issue, not least because they were worried about the expense—and so things went on in the same old unsatisfactory way.

Around the time of his thirtieth birthday Stefan asked his father if he could stop paying him the monthly allowance from the family fortune and instead make over a capital sum that he would invest and manage himself. After some discussions with his wife’s cousin, the bank director Eugen Brettauer, who in earlier years had also been the family lawyer, Moriz Zweig transferred the sum of 400,000

kronen

to his younger son. He subsequently made provision in his will for Alfred to receive a similar sum.

During this time Stefan made some interesting new acquaintances. One of them was the young photographer Franz Xaver Setzer, who photographed him many times over a period that extended into the 1920s. The resulting portraits are plain and unadorned, often seeming a little distanced, and were regarded as very modern at the time. Setzer’s studio had quickly acquired an excellent reputation, and attracted illustrious clients. Among the names listed in the appointments diary are Arthur Schnitzler, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Peter Altenberg and Felix Salten. When Setzer married the soprano Marie Gutheil-Schoder from Weimar, prominent figures from the world of theatre and music were soon added to his list of clients. Giacomo Puccini, Erik Frey and Max Reinhardt came to have their portraits taken, and Reinhardt’s wife, the actress Helene Thimig, posed in costume before the camera, along with her colleagues Hedwig Bleibtreu and Paula Wessely. Zweig valued Setzer’s acquaintance not only as a pivotal figure of the Viennese cultural scene, but also as someone he could talk to about his growing interest in photography. Zweig had begun to dabble in this field at an early stage. His observations in the darkroom even led him to draw parallels with his own artistic endeavours: “All creative writing always puts

me in mind of the process of photographic development. You start with the empty plate, then sketchy lines appear, like a veil, which then become clearer, more visible and sharply defined”,

6

he wrote in a letter to Paul Zech. Unlike his literary work, however, it seems that virtually none of his own photographs have survived.