Three Lives: A Biography of Stefan Zweig (28 page)

Read Three Lives: A Biography of Stefan Zweig Online

Authors: Oliver Matuschek

As Alfred later wrote, it seemed to him at the time that Stefan had stumbled into marriage with Friderike during a phase of insecurity and personal neediness. Since Stefan had always valued his personal freedom above all else, he had never really been suited to a permanent union. So Alfred concluded that it was not love and affection but Stefan’s strong sense of duty and pressure on Friderike’s part that had kept the relationship going and led finally to marriage. And the marriage had not worked right from the beginning, according to Alfred—there had always been substantial differences between Friderike and Stefan. Indeed, the marriage had been contracted “subject to some rather curious reservations”, as Alfred wrote to Richard Friedenthal, adding that he could only elaborate on this, as on so much else, when they were able to meet and talk—which in the event never happened.

8

Writing decades after the death of his brother, and already influenced in part by Friderike’s published volumes of memoirs, Alfred had harsh words to say on the subject in various letters. His statements need to be treated with some degree of caution. However, in a list of questions, many of them very personal, which the literary scholar Donald Prater put to Friderike in the early 1970s, when he had already completed his biography of Stefan Zweig, he had also asked her whether their marriage had been more of an “elective affinity” or a “physical union”.

9

While Friderike answered all his other questions, including some of an even more personal nature, she chose not to answer this one.

Only now, with the move to the Kapuzinerberg, would Stefan be living for any length of time with Friderike and her daughters Suse and Alix in the same place, and indeed under the same roof. Their previous family life, if indeed one can speak of such a thing, had been characterised by a restless coming and going. The few months in the rococo pavilions in Kalksburg were the only time they had actually lived together, but even then Stefan had spent his days at work in the War Archive. The rest of the time they had rarely been together, living instead in separate apartments, hotels, boarding houses and children’s homes.

Looking back after many years, Friderike’s account of Stefan’s arrival in Salzburg, marking the start of their family life together, strikes an almost ceremonious note:

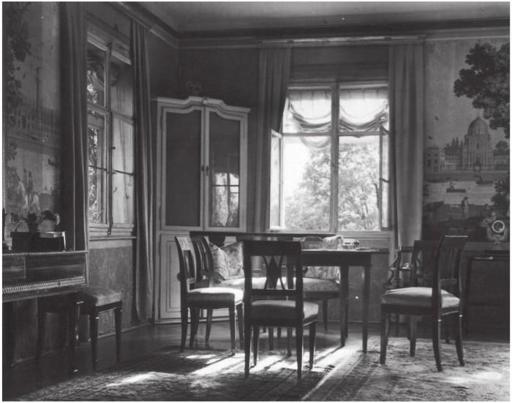

The garden in Salzburg was resplendent with fruit trees in full blossom when Stefan made his entrance on the Kapuzinerberg. He took two rooms for himself, which opened onto a vast terrace, and a very large library room on the ground floor, next door to which a fairly large office was later established, which was likewise filled with books and his steadily expanding collection of autograph catalogues. Next door to his rooms upstairs was the “saloon”, a large rococo room decorated with scenic wallpaper by the famous French wallpaper designer Dufour. Leading off from this beautiful and unique room was my tiny salon with balcony, my bedroom, the bathroom and the nursery. There was also an attic, the little turret, a garden room downstairs with old-fashioned panelling and a laundry room and glasshouse leading off it, and on the floor below that two rooms for servants and a huge kitchen.

10

The house stood very close to the Capuchin monastery from which the hill derived its name, and was reached from the town via an archway in the Linzergasse. From here a steep and barely paved path led up to the house. So in effect they were not living in Salzburg so much as above it. At all events the house occupied a very special position, which may not necessarily have been a reason for buying it, but was very welcome nonetheless. Here Stefan Zweig would establish his future workplace, where he hoped to realise at last the many projects that he had been planning, some of them shelved for years. Looking back, it is interesting to note that most of the works he had completed up to the year of his arrival in Salzburg are now largely unknown. One rarely comes across poems by Stefan Zweig today, nor are his plays very often performed.

Before life in the villa with its idyllic gardens could be enjoyed to the full, it was necessary to get rid of some dubious characters who associated with the children of the former gardener. Until the new owners moved in they had occupied a section of the house. For a brief period the daughter was hired as a maid, while the son, who had a fondness for poaching and wild binges with his mates in the garden house, posed “an interesting pedagogical problem”,

11

as Friderike put it. While Stefan was still away in Vienna she had taken steps to provide some additional amenities. So when he arrived a telephone had already been installed (telephone number Salzburg 598), with an extra bell, whose continuous ringing was audible even from the far corners of the garden. In the course of the year, depending on the outside temperature, Zweig would transfer from his summer study with its outside terrace to his warmer winter study.

The house on the Kapuzinerberg in Salzburg

The interior of the ‘saloon’ in the house on the Kapuzinerberg

In the end Friderike had to agree to the decision to employ a new secretary to replace Frau Mandl, but from the outset she seems to have kept a very close eye on the activity of the new assistant at her husband’s side. From a shortlist of three candidates for the post Zweig chose Anna Meingast, a native Viennese, whose husband had been killed in the war. Shortly after his death she had moved to Salzburg, where her in-laws lived. Together with her son Wilhelm, born in Vienna and now four years old, she lived in the Laubinger House in the Linzergasse, very close to the archway through which one ascended the path to the top of the Kapuzinerberg. Prior to her appointment in 1919 Anna Meingast had taught shorthand, and for nearly twenty years she would handle the bulk of Stefan Zweig’s correspondence, copy his manuscripts and take care of the filing. Her normal working hours were from 1.00 pm to 6.00 pm.

Even though Zweig himself wrote that he had lost the taste for long-distance travel since he came to live in Salzburg, he was far from being settled. He must have been referring to overseas travel only, because he continued to spend several weeks or months each year away from home. Not without good reason did Romain Rolland later speak of the “Flying Salzburger”, personified for him by Zweig with his tireless love of travel.

In the autumn of 1919 Zweig was able to report on the successful premiere in Vienna of his

Jeremias

, which he had attended in person. Shortly after that he was touring Germany again, giving his Rolland lecture in Hamburg and reading from his own works in Kiel and other cities. The impressions of the war years and the ideals of peace and non-violence that he had developed during this period were never far from his mind. His sense of his own Jewish identity had changed hardly at all from the views he had expressed earlier. He was troubled by the anti-Semitism that he saw being propagated ever more openly, but he remained unsympathetic to Zionist thinking and the idea of establishing a separate state in Palestine. He reiterated his views on the subject in a letter to Marek Scherlag:

I see it as the mission of the Jews in the political sphere to uproot nationalism in every country, in order to bring about an attachment that is purely spiritual and intellectual. This is why I also reject Jewish nationalism, because arrogance and a desire to be separate are part of the package: having sown our blood and our ideas throughout the world for 2,000 years, we cannot go back to being a little nation in a corner of the Arab region. Our spirit is cosmopolitan—that’s how we have become what we are, and if we have to suffer for it, then so be it: it is our destiny. It’s no use being proud or ashamed of one’s Jewishness—you just have to acknowledge it for what it is, and live as our destiny dictates, namely homeless in the highest sense of the word. So I think it is no coincidence that I am an internationalist and a pacifist—I would have to deny myself and my blood if I were anything else! In Jeremias too the message of the play is against any realisation of our nationalist aspirations—they are our dream, and as such more precious than if they were actually to come true.

12

By the end of the year, with the aid of Friderike and the new secretary, Zweig’s work was going reasonably well on the Kapuzinerberg. There was a lot of catching-up to do. In December Zweig wrote to Seelig: “For months now most of my time has been taken up with correcting the proofs of my books and waiting for them to come out; I have four new editions and three new books, but everything now seems to be taking for ever.”

13

The delays were not Zweig’s fault, and he could not wait to see his books back in print again. But in the coming years various administrative problems at his publishers, ranging from financing issues to paper shortages, would test his patience repeatedly: “It’s all chaos and uncertainty now. And it’s hard to get used to, when one comes from three generations of bourgeoisie!”

14

Difficulties of this kind would prove persistent. At the beginning of 1922, for example,

Jeremias

was no longer available in the bookshops, but despite plenty of pre-orders it could not be reprinted because the printing paper, on order for a long time, never arrived. For upcoming editions of various titles the author and publisher’s editor agreed on the use of a smaller typeface in order to reduce the number of pages, and thus keep the consumption of precious raw materials to a minimum.

Fortunately the first winter in their new home was relatively mild, so that the inadequate heating arrangements were not too much of a problem. Zweig could easily do without the saloon, but for the time being he transferred the most important works from the library on the floor below to his study. As he wrote to his editor, Fritz Adolf Hünich, when the latter sent an urgent request for some information from a particular book that Zweig owned: “I can only bear to descend into that icy pit from my warm room for a few minutes at a time”.

15

Amidst all the work, the wedding was at last due to take place at the start of the New Year. The decision had been delayed for weeks and months, and it had profited them nothing that Friderike had left the Catholic Church in July 1919, simultaneously submitting an application to have her special circumstances taken into account. The necessary decisions sanctioning a so-called ‘dispensation marriage’ were batted back and forth by the

higher authorities from one office to another, while Zweig stood by with mounting impatience. When the requisite document was finally issued, it was decided to hold the wedding in Vienna rather than in provincial Salzburg, in order not to make the affair even more unpleasant for all those involved by exposing them to local tittle-tattle and gossip.

Stefan travelled to Vienna several days before the wedding and stayed with his parents in the Garnisongasse, where he seems to have been in cheerful mood. He wrote to Friderike that he had made the journey, regrettably, “in entirely unfemale company”.

16

Back among his Viennese friends he spent many an amusing hour, and sent out a curious invitation:

Dear Friend,

As Felix may already have informed you, I should like to request your attendance tomorrow, Wednesday 28th January, at the homosexual ceremony. We are meeting at 10.30 am at the Café Landtmann.

The big event takes place at 11.00 am, it should all be over by 11.45.

So I will look forward to seeing you there!

Yours sincerely,

Stefan Zweig.

17

Taken out of context, this undated announcement may well raise a few eyebrows. However, from the reference to the day and the month it is possible to date the document definitively to the year 1920. And everything becomes clear when we look more closely at the impending wedding—when all was said and done, it was more of a tiresome bureaucratic formality than an occasion for rejoicing. There were no wedding photos, no cake, no great family celebration and very likely no wedding rings. Certainly later photographs of Stefan Zweig show him wearing no ring other than the narrow gold band with a precious stone on the little finger of his left hand, which he had worn since 1912 or thereabouts (and whether this relates to the fact that he met Friderike that year is purely a matter for speculation). More curious yet—the bridal couple were not even both present when the marriage was solemnised. With the painful memories of her divorce still fresh in her mind, Friderike preferred to stay away from the wedding, asking their friend Felix Braun to represent her instead. Also present as official witnesses to the marriage were Hans Prager and Eugen Antoine, while Stefan’s brother Alfred represented the Zweig family. Consequently on the day named in the invitation to the “homosexual ceremony”, 28th

January 1920, it was an exclusively male company that assembled in the registrar’s chambers in the Town Hall of Vienna, just a short walk away after crossing the Ringstrasse from the Café Landtmann. The wedding began punctually at 11.00 am, although the atmosphere of solemn formality threatened to dissolve into mirth when the registrar, reciting the standard form of words for the occasion, expressed the hope that the happy couple would be blessed with many children, whereupon the groom, flanked by the bride’s male representative, burst into laughter.