Three Lives: A Biography of Stefan Zweig (27 page)

Read Three Lives: A Biography of Stefan Zweig Online

Authors: Oliver Matuschek

The Austrian train that brought Zweig and his party to Salzburg was notably different from its counterpart operated by the Swiss Railways. The windows had been broken and patched up in makeshift fashion, all the leather trimmings inside the coaches had long since been stripped out by earlier passengers to repair shoes and clothing. In the train compartments and on the platforms one saw endless haggard figures and soldiers in shabby uniforms. “Hell lay behind us”, wrote Zweig of the situation, “what could possibly frighten us after that? Another world was beginning.”

27

It was a journey into a new world—and into a new life, as Zweig was only too well aware.

NOTES

1

16th November 1917, Zweig GW Tagebücher, p 259.

2

Stefan Zweig to Eugenie Hirschfeld, 4th August 1906. In: Briefe I, p 127.

3

17th November 1917, Zweig GW Tagebücher, p 262 f.

4

Stefan Zweig to Insel Verlag, 16th November 1917, GSA Weimar, 50/3886, 2.

5

Stefan Zweig to Insel Verlag, 17th November 1917, GSA Weimar, 50/3886, 2.

6

Romain Rolland. Vortrag, gehalten im Meistersaal zu Berlin, Sonnabend, den 29. Januar 1926. In: Zweig GW Rolland, p 384.

7

Zweig 1922, p 9.

8

Stefan Zweig to Hermann Ganz, 6th December 1917, ZB Zurich, Ms. Z VI 397.7.

9

Zweig F 1964, p 83.

10

Marginal note by the Foreign Minister Ottokar Graf Czernin von Chudenitz to a report by the Austro-Hungarian Embassy in Bern, copy in the archive of S Fischer Verlag.

11

14th January 1918, Zweig GW Tagebücher, p 303.

12

Mitteilungen 1918.

13

Beran 1918.

14

Austro-Hungarian Embassy in Bern to the Foreign Ministry in Vienna, 15th July 1918, copy in the archive of S Fischer Verlag.

15

Enquiry order and report on Stefan Zweig at the Hotel Belvoir in Rüschlikon, 27th July and 1st August 1918, SBA Bern, E 21/10574.

16

Stefan Zweig to Friderike Maria von Winternitz, undated, probably mid-July 1918, SUNY, Fredonia/NY.

17

Stefan Zweig to Carl Seelig, undated, summer 1918, ZB Zurich, Ms. Z II 580.183a.

18

Zweig F 1964, p 39.

19

Stefan Zweig to Romain Rolland, 18th December 1918. In: Briefe II, p 548.

20

Stefan Zweig to Anton Kippenberg, 6th January 1919. In: Briefe II, p 556 f.

21

Zweig GW Welt von Gestern, p 8.

22

Stefan Zweig to Friderike Maria von Winternitz, late January 1919. In: Briefwechsel Friderike Zweig 2006, p 84.

23

Ida to Stefan Zweig, 23rd January 1919. In: Briefwechsel Friderike Zweig 2006, p 83 f.

24

Stefan Zweig to Friderike Maria von Winternitz, undated, c. 20th January 1919. In: Briefwechsel Friderike Zweig 2006, p 82.

25

Ida Zweig to Friderike Maria von Winternitz, undated, early February 1919. In: Briefwechsel Friderike Zweig 2006, p 85.

26

Zweig GW Welt von Gestern, p 326.

27

Zweig GW Welt von Gestern, p 322.

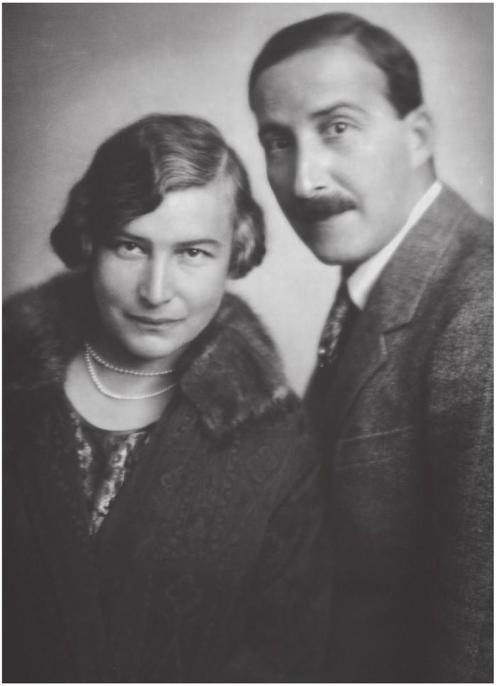

Friderike and Stefan Zweig in 1926

After the war I returned to a crippled, starving Austria, but this time not to Vienna, not to my old life

.

1

Autobiographical note 1922

“F

OR THE PAST FOUR DAYS

the author of

Vögelchen

has been known as Friderike Maria Zweig. We are married at last.”

2

With a sigh of relief Zweig sent this message to his friend Carl Seelig in Zurich at the beginning of February 1920. Since their arrival in Salzburg in the spring of 1919 the start of their new life had been delayed by a protracted struggle to secure permission for the marriage. Zweig had written to Anton Kippenberg prior to their departure from Switzerland and talked about the obstacles that continued to stand in the way of a wedding:

I have been living for years in sin (but feeling very blessed) with Frau von Winternitz, to whom my

Jeremias

is dedicated [ … ]. Since she divorced as a Catholic, to have married a second time in Austria would have been bigamy for her, and therefore punishable by law. Well, we waited patiently until the old Austria was dead and gone, and in May or June we’ll be moving to Salzburg, where a modest chateau with a wonderful garden is going to be pretty much the sum total of our once substantial fortune, with perhaps a small pension thrown in too, if Comrade Spartacus leaves us in peace. But I have long since drawn a line under all that, I know that if things calm down I’ll get by all right, a house and a garden are all I’ve ever wanted. And if things don’t work out, I’ll just auction my collection. After the last five years I just want to be back in my own room surrounded by my books.

3

After the end of the war the political uncertainty was greater than ever. In Germany as in Austria, marginal and splinter groups from both ends of the political spectrum attempted to influence, with slogans if not with deeds, the negotiations that would shape the peace treaty and the future of Europe. So Zweig’s allusion to the Marxist

Spartakusbund

does not come out of nowhere. But the hope that the end of Imperial Austria would bring

with it a reform of Austria’s Matrimonial Act, clearing the way for an early wedding, proved illusory. The matter was by no means a mere formality. And so began a bureaucratic obstacle race, like the one Zweig had documented at the beginning of 1919, following his efforts to secure various visas and travel permits, in a feature article entitled

Bureauphobie

—with a nod also to his own clerical work at the War Archive. In a fictional letter to a doctor the author describes the alarming symptoms (“a pounding heart and a nasty sensation in my throat”, plus a “feeling of helpless nausea”) that afflict him the moment he enters an office, or even contemplates the prospect of having to do so. Then he is gripped with a terrible pain, the self-diagnosis continues, not “some minor psychotic episode that will soon pass”, but “that malady, the fear of offices, from which I fear I shall never quite recover”.

4

After his departure from Switzerland Stefan Zweig had stayed only briefly in Salzburg before journeying on to Vienna to see his family and friends again for the first time in years, and to attend to the sorting, packing and shipping of his belongings from the apartment in the Kochgasse. He also had to organise the necessary paperwork for the move to Salzburg.

At their new home on the Kapuzinerberg, meanwhile, Friderike had her own problems to deal with. The work on the house was nowhere near finished, there was a shortage of building materials, and on top of everything else there was a possibility, given the general housing shortage, that they would be forced to give up parts of their new home to strangers for an indeterminate period. And then the Swiss governess had fallen ill with appendicitis as soon as she arrived. One doctor wanted to charge an extortionate fee for her treatment, so Friderike went to much time and trouble to sort out affordable medical care for her—whereupon Loni Schinz left to go back to Switzerland. A little later the children’s former nanny, Lisi Exner, was able to join them from Vienna, her required residence permit for Salzburg having been organised—once again—by Friderike’s former father-in-law.

From her provisional base in the Park Hotel Nelböck Friderike endeavoured to supervise both the care of her children and the progress of the building works. The situation would prove to be a foretaste of what lay ahead in the coming years—when domestic life threatened to become too chaotic, it was Stefan who took off on his travels, leaving her behind to do the work. On the one hand Friderike would probably have welcomed his active support in such situations, but on the other these were precisely the times when she could demonstrate once again her strong organisational skills. The man of the house fully appreciated those skills, because his work schedule

made no provision for any active involvement in the running of the house. Once he was sufficiently far removed from the seat of domestic unrest, he was even known to style himself genially in letters as “Stefan Pascha”. If one reads Friderike’s memoirs from this perspective, her achievements as a homemaker would seem to have played a big part in affirming her singularly robust self-confidence.

After his departure from Salzburg Stefan Zweig spent nearly eight weeks in Vienna. He was due to move out of the apartment in the Kochgasse on 24th April, after which he planned to stay with his parents in the Garnisongasse until 8th or 10th May. He had re-engaged his former servant Josef and his secretary Mathilde Mandl to help with the preparations for the move. Both were kept busy packing up his books and the contents of his filing cabinet, since Zweig could barely bring himself to give anything away or weed anything out. Just a handful of books that he thought he no longer needed were sold to second-hand bookshops. As so often in the past, Frau Mandl’s motherly yet efficient presence was an enormous help to him, and he would dearly have liked to employ her services in his office in Salzburg. She would have been willing to come, too: but Friderike raised serious objections, and so his loyal amanuensis stayed behind in Vienna.

Stefan also took time to trawl through his parents’ apartment and attic, looking for items of furniture and household goods that he could use. He reported back to Friderike on the results:

I uncovered a real treasure at my parents’ place: a very old and magnificent iron travel trunk belonging to my Italian grandfather, the perfect thing for my manuscripts. It’s been up in the attic for the past twenty years, and I had no idea it was there. I’m also getting some cash, twenty or thirty [thousand Austrian kronen], which will cover the most essential costs. So it is all going pretty well here, just as long as the Communists don’t take over next week. [ … ] Frau Mandl has located some very good mattresses at a friend’s house, my mother has blankets, and Alfred is giving you a carpet, so I hope that it will all be all right.

5

But after years of uncertainty it was now time to get back to his main business, namely working on new books. In early April Zweig invited Carl Seelig to come to Vienna for preliminary discussions on a new project. “It’s all looking lovely here, and quite different from what I expected: no sadness, no despair, people [ … ] are just living for the present with amazing insouciance, and spring has long since lifted everyone’s spirits”,

6

as he wrote in his letter to Zurich. All the same, he told Seelig that it would make his daily life in Vienna easier if he came provided with a special currency, and based on his own experience Zweig strongly recommended that he bring a supply of cigars and Swiss chocolate with him. “People here will throw their arms around you and lionise you for it.”

7

The end result of the negotiations resulting from these preliminaries was a contract signed by Zweig and Seelig for a book to be called

Fahrten

[

Journeys

], a collection of Zweig’s feature articles and poems on landscapes and cities that would form part of the series

Die zwölf Bücher

published by E P Tal. A fee of two thousand

kronen

for an initial print run of one thousand copies was agreed.

In April Zweig gave a lecture on Rolland in Vienna, using some of the material he had collected for the book he was now working on. Friderike von Winternitz—or more correctly Friderike Winternitz, since aristocratic titles were no longer officially used in Austria—arrived in the city around the same time. The time had finally come for the first visits to each other’s in-laws. Friderike’s widowed mother was living alone, and now met the man who, it was hoped, would soon become her son-in-law, while Stefan’s parents made the personal acquaintance of the lady who intended to marry their younger son, and with whom Ida Zweig had already corresponded. Friderike felt herself warmly received, and became fond of Stefan’s parents in her turn, as she wrote in her memoirs; but she can hardly have failed to notice that the Zweig family was not wildly enthusiastic about the prospect of her proposed marriage to Stefan. Alfred in particular had serious reservations. Why, in these unsettled times, when the family business faced an uncertain future and there was no guarantee that they would be able to maintain their former standard of living, did his brother have to choose this moment to marry a divorced woman with two dependent children? Alfred will not have been much reassured by the fact that Stefan was not planning to adopt the two children, and that Friderike intended to carry on providing for Suse and Alix by herself. What were the real prospects of this woman achieving any literary—and therefore financial—success? Wouldn’t his brother end up spending his own money—and that of the family—to support them? And anyway, would his own writing prove profitable in the long term? One thing was certain—once Stefan had left Vienna, Alfred, who still spent most of his time in the city, would become solely responsible for the care of their parents, both of whom now suffered from poor health.