Three Lives: A Biography of Stefan Zweig (54 page)

Read Three Lives: A Biography of Stefan Zweig Online

Authors: Oliver Matuschek

Unsettled by all this controversy, which was the more disagreeable because President Vargas ruled his country with a dictatorial hand, Stefan was soon seeking to retreat into his work again. He and Lotte spent a great deal of their time in Petrópolis, where they had few visitors. They met up fairly frequently with Stefan’s publisher Abrahão Koogan in Rio, and occasionally with Friderike’s brother Siegfried Burger, who was living there with his wife Clarissa and son Ferdinand. Another frequent companion was the Berlin newspaper editor Ernst Feder, another European exile who had fetched up in Petrópolis, whom Zweig met for long talks and games of chess—shades of the ‘Chess Fox’ from his Salzburg days. He had retained a keen interest in the game, and had drafted a novella about a man who was persecuted and imprisoned by the Fascists, and who sought to escape into a secure world of his own by playing chess with an imaginary opponent.

Slowly but surely, Stefan came back from his low point in Ossining, turned again to his manuscripts and found new hope. His second novel,

Clarissa

, was already sketched out, and in browsing through some books that Feder had lent him he had come across yet another historical figure, in the person of the humanist Michel de Montaigne, to whom he planned to devote an extended essay. In a letter to Felix Braun he recounts how he feels much more at home in the “Latin sphere” of Brazil than in the USA. In describing his new domicile he once again resorts to a comparison with his native country, calling Petrópolis “a kind of miniature Ischl”. He goes on: “We have rented a tiny bungalow, we have a black woman servant, everything is splendidly primitive, donkeys laden with bananas walk right past our windows, all around us are palm trees and virgin forest, and the starry night sky is just amazing. What we miss are books and friends.”

14

The isolation was also difficult for Lotte. She was afraid that she might bore Stefan with talk about the mundane details of their daily life. She had yet to find a friend of her own sex with whom she could converse, and so she spent a great deal of time trying to communicate with their housemaid Aurea in a language that was still very foreign to her. They planned the menu together for the week ahead, and she was soon able to report: “She has learnt (and so have I) to make Palatschinken, Schmarren and Erdäpfelnudeln & other ‘European’ dishes”.

15

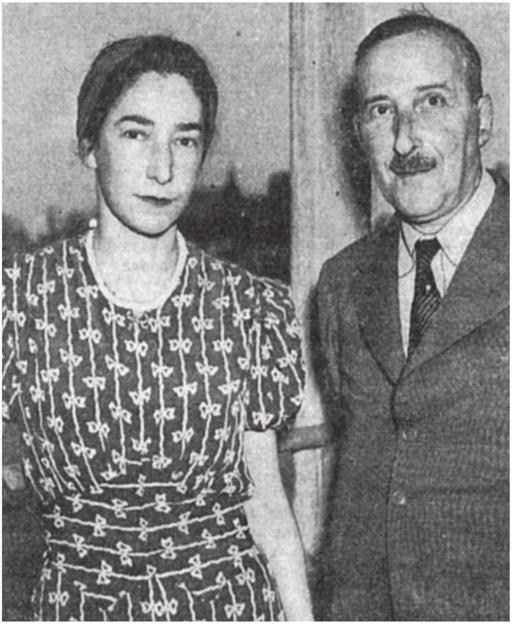

Lotte and Stefan Zweig

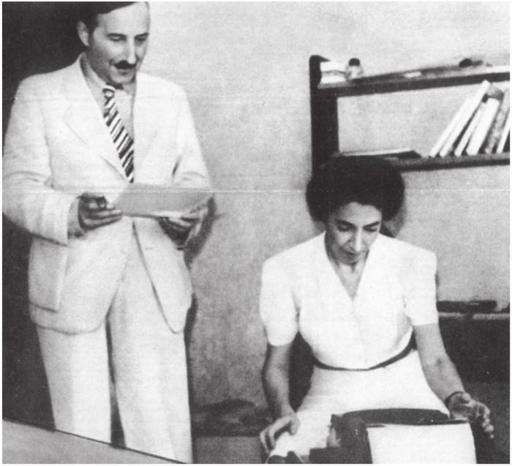

Stefan and Lotte Zweig at work in Petrópolis

At the beginning of December 1941 Lotte and Stefan spent a day in Rio. While he prepared himself for various meetings and went to the barber’s shop to get a shave, Lotte used the time to write a long letter to her sister-in-law Hannah. In it she was happy to report that Stefan was now feeling better again. His view that everything was pointless while the war was on, and even after the war was over, had changed, and he was now taking pleasure in his work again. He was even hoping to borrow some books from friends and colleagues. Lotte’s strategy—to get him writing again, and thus help him out of his depression—seemed to be working. The manuscript of

Die Welt von Gestern

—the new title he had chosen for his autobiography—was finished, and as yet he did not know what project to tackle next. So Lotte asked her sister-in-law to locate the ring binder in Bath that contained Zweig’s notes for the Balzac biography, and, if at all possible, to get them typed up by Richard Friedenthal. She asked for this back-up copy to be sent to Petrópolis so that Stefan could continue with his ambitious project, which was likely to occupy him for years to come.

This news was doubly surprising in that Stefan’s sixtieth birthday, which represented a major hurdle in his life, had passed just a few days previously. In recent weeks Lotte had enlisted the help of others around her in her efforts to provide for her husband. Thus she had been able to secure an antiquarian edition of Balzac’s works, which she presented to Stefan on his birthday. And Koogan, who accompanied them on a birthday outing, had brought a ten-month-old wire-haired fox terrier with him as a present (to his great regret, a spaniel had proved impossible to find in Rio and the surrounding area). To all those who had sent him birthday greetings Zweig sent copies of a poem entitled

Der Sechzigjährige dankt

[

A Thank-you from the Sixty-Year-Old

]:

More lightly now the passing hours

Touch the hair that turns to grey

Only the cup that’s nearly drained

Reveals its floor of gold at last.

Premonition of approaching night

Comes not as pain but as release.

Pure delight of worldly contemplation

Knows only he who nothing more desires,

And nothing cares for past success,

Laments no more the things undone,

And finds that growing old in years

Is just a gentle way to start to leave.

Never is the prospect clearer

Than in the glow of the departing day,

Never is life more truly loved

Than in the shadow of renunciation.

16

He seems to have got over the birthday, and everything that it entailed, remarkably well, and in his seclusion Stefan found increasing pleasure in the research for his Montaigne project. On Christmas Day he wrote to Joachim Maass and reported on the progress of his work. The little “chess novella” was finished, although he would have liked to have it checked for accuracy by a professional chess player. The novel, on the other hand, was not really making much progress, but the essay on Montaigne was looking very promising: he saw himself and his own circumstances mirrored in this historical figure, as he had years before in his

Erasmus

—and this manner of portraying his own sensibilities was what so appealed to him: “Anything theoretical is a closed book to me. The only way I can express myself to any degree is through flesh-and-blood characters and symbolic forms.”

For the rest, he reports as follows:

Outward life: a monotony that calms the nerves in a magical landscape. Company: the local natives, whose speech I only partly understand, but who are touching in their kindness, warmth and primitive simplicity. Intellectual nourishment: a complete edition of Balzac, Montaigne and Goethe—so no friends under two hundred years. Companions: a sweet one-year-old fox terrier that I was given for my birthday, who is visibly contributing to the onset of childishness in my old age.

17

The Christmas card that Stefan and Lotte sent to his sister-in-law in New York had a striking picture on the front, a collage of brightly coloured butterfly wings depicting the Sugar Loaf Mountain in Rio—which really did look just like it did in the picture, wrote Lotte. Stefan added a combined Christmas and birthday greeting for Stefanie (26th December being both her birthday and her Saint’s day). The card was signed by him, Lotte and also—in the old Salzburg tradition dating back to the time of Kaspar—by “Plucky”, to which Lotte had added the explanatory parenthesis “(dog)”.

18

Over a period of several months Zweig’s letters from Petrópolis contained few references to the war, which only a short time before had been an almost constant preoccupation. But the calm was deceptive. Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor the USA had entered the war, which now threatened to escalate into a true world war. So it seemed only a matter of time before Brazil, too, became directly involved in the hostilities, either as a result of U-boat attacks in the Atlantic or by some other means. Censorship restrictions were imposed, letters to the USA could no longer be written in German—now the language of the enemy—and the postal connection, slow at the best of times, was now further delayed by security controls and the war at sea.

In Petrópolis as in Bath, Zweig had become a “Radiot”, listening every day to the latest news of disaster on his little Philco radio. In his imagination he had repeatedly pictured the most horrific scenarios, which again and again were trumped by the reality as events unfolded. So as 1942 began, he found himself sinking into depression once more. He had already fled with his wife to the ends of the earth: where else was left for them to go? In a letter to Friderike of 20th January 1942 he gives voice to his bitterness and despair, but the tone is calmer and more composed now: “It is becoming increasingly clear to me that I shall never see my own house again, and that wherever I go I shall just be a wanderer on the face of the earth. Those who are able to start a new life wherever they are can count themselves fortunate. [ … ] The only path open to us now is to quit the scene, quietly and with dignity.”

19

For a long time now he had felt that he was approaching the end of his “third life”—and he knew that he had no heart for embarking on a fourth.

On 13th February 1942 Ivan Heilbut walked into a New York post office with a letter to be sent by registered mail (No 436 248) to Petrópolis. Apart from the covering letter to Zweig, the envelope contained a copy of Heilbut’s freshly completed collection of poems and an attached prospectus, announcing that the poems were soon to be published in a book entitled

Meine Wanderungen,

with a preface by Stefan Zweig. In the letter he asked Zweig if he could now send him the brief text he had promised to write. For a long time Heilbut remained uncertain whether his letter had ever reached its intended recipient. Weeks later he submitted a tracking request, and finally learnt on 4th June that his letter had been delivered to Zweig on 21st February.

20

But Heilbut never received a reply to his letter; his book was published later that year in New York, with a foreword containing a dedication to Stefan Zweig.

21

On 21st February 1942 Alfred Zweig received a letter from his brother. The letter had taken more than a week to get from Brazil to New York. The most important piece of news Stefan had to report was that he was pleased to be able to rent the house in Petrópolis for another six months, since the present rental agreement was due to expire in a few weeks. But in the time between the dispatch of the letter and its arrival, dramatic events had taken place. On the very day that Alfred was reading the letter, a Saturday, Stefan posted carbon copies of the completed manuscript of his

Schachnovelle

[

Chess Novella

] to his publishers Huebsch and Bermann Fischer, sending another copy to his Argentinian translator Cahn. He also took a number of smaller envelopes to the post office, addressed to friends and relatives. He had come to a decision—the envelopes contained his valedictory letters.

At the beginning of this week he and Lotte had travelled to Rio at the invitation of the Koogans to see the famous carnival. On the Tuesday morning the press was filled with reports that Singapore had fallen to the Japanese, whereupon Stefan and Lotte left immediately to return to Petrópolis, much earlier than planned. This latest Allied defeat appears to have been seen as a sign by Stefan. Over the next few days he worked through a list of things to do that included putting all his papers and publishing affairs in order. His study of Amerigo Vespucci was already with the publisher and due to come out soon,

Die Welt von Gestern

, his major autobiographical work, was also ready for publication, and the book went on sale later that same year. His novel

Clarissa

, the book on Montaigne and the major biography of Balzac remained fragments only, bequeathed to us as part of Zweig’s literary estate, and later published as separate volumes in the collected edition of his works.