To Reach the Clouds (12 page)

Read To Reach the Clouds Online

Authors: Philippe Petit

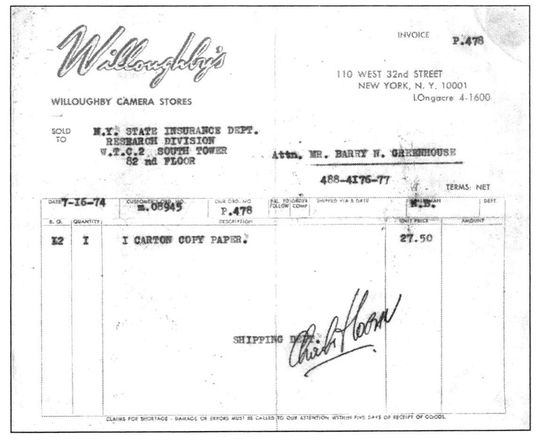

What better way to find out how heavy equipment enters the towers than to organize a phony delivery?

Barry agrees to receive the goods.

But first I need two new accomplices to replace the Australians.

Â

I learn that Jim Moore is struggling to remove the linoleum flooring of his newly acquired loft at the corner of Hudson and Chambers. We spend two days breaking our nails and dulling blades: the linoleum is glued to the wood with some kind of tar and breaks off only an inch at a time. Each time we take a rest, I discuss WTC. Again I ask my friend to help on the roof. Again the answer is no.

Â

The next morning, two Americans who live in the building bump into Jim in the lobby and ask if his friend the Frenchmanâthey've passed me in the elevatorâis the tightrope walker, the

guy who's looking for a place to put his wire. They recognized me from the article and the TV.

guy who's looking for a place to put his wire. They recognized me from the article and the TV.

“Uh-huh,” mumbles Jim.

“Well, you can tell him we've come up with a terrific idea, a site that will blow his mind.”

“What's that?”

“The top of the World Trade Center!”

Well trained, Jim breaks out laughing, but thinks to askâin case his friend Philippe loves the ideaâwould they be ready to help him?

Receiving an enthusiastic chorus in response, Jim arranges a meeting.

Â

Annie and I show up the next day, upstairs in a dark loft.

Donald, with curved shoulders and long, thinning hair in a ponytail, is at the piano whining out a new song in a high-pitched voice; he's a rock musician. Chester, with thick glasses and a bushy head of hair atop a body too long and too thin, pouts sadly. He is a carpenter.

I show the album, I open the

cahiers

, I display accordions of WTC pictures. Donald and Chester are astounded by the extent of my preparations. They are ready to take part. I ask them to promise not to tell anyone, and they do.

cahiers

, I display accordions of WTC pictures. Donald and Chester are astounded by the extent of my preparations. They are ready to take part. I ask them to promise not to tell anyone, and they do.

Â

I don't suffer dismal faces gladly, and I don't appreciate rock and roll music, but I have no choice.

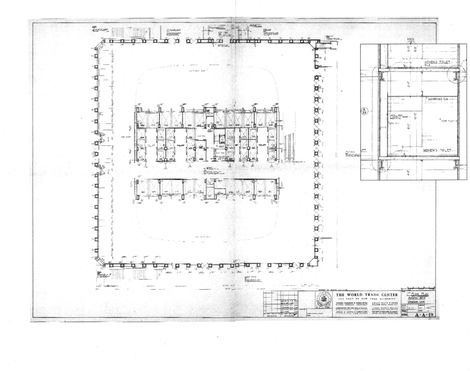

Without telling me, just prior to his disappearance Paul had written a letter to Emery Roth and Sons, the firm that designed the towers, introducing himself as an architecture scholar and requesting help in his study of WTC.

Â

The protective envelope I tear open this morning spills out its

priceless contents all over the sofa: ten off-white sheets, 18 by 25 inches, covered with blueprints:

priceless contents all over the sofa: ten off-white sheets, 18 by 25 inches, covered with blueprints:

1ST FLOOR

9TH TO 16TH FLOOR

35TH TO 40TH FLOOR

44TH FLOOR / SKY LOBBY

50TH TO 54TH FLOOR

78TH FLOOR / SKY LOBBY

96TH TO 100TH FLOOR

107TH FLOOR / RESTAURANT LEVEL

9TH TO 16TH FLOOR

35TH TO 40TH FLOOR

44TH FLOOR / SKY LOBBY

50TH TO 54TH FLOOR

78TH FLOOR / SKY LOBBY

96TH TO 100TH FLOOR

107TH FLOOR / RESTAURANT LEVEL

There is also a superb 9TH TO 10TH FLOOR/CORE PLAN, plus a gorgeous CROSS SECTION THRU TYPICAL FLOOR detailing men's and women's toilets and clearly showing the suspended ceiling and the lost space above it, which I've already explored and deemed an excellent hiding place. I measured its height to be 3'6”. Here, the drawing indicates 4'0” from suspended ceiling to the top of the 4-inch concrete slab; that's a height of 3'8”. Well, nobody's perfect. I earmark the sheet, though; after the coup I'll check, maybe it's

their

mistake â¦

their

mistake â¦

A kid on Christmas Day, I rummage through my WTC files and compare the few old and out-of-sequence blueprints (which “fell into my bag” during my countless shadow visits) with the pristine documents destiny has just awarded me.

Although instantly my most prized possession, this bunch of blueprints is perfectly useless. Nonetheless, they make me feel professional: when you plan a bank robbery, first you acquire blueprints, right?

Â

Â

“Hey, you!”

One of Annie's feral kittens is walking on the 78th floorâpeeing on the elevator shaft! I grab the trespasser by the tail and send it flying into the garden. The cliché is true: they do always land on their feet.

Then I take a look at the handwritten message from one Joseph H. Solomon, the fourth name on the firm's letterhead, wishing Paul the best and concluding, “If you ever receive a commission to do a 110-story building in Australia, we will be happy to act as consultants or co-architects.”

Â

Thank you, Paul, thank you, Joseph, thank you, God.

I am ready to try the false delivery to Barry's office. As it is just a drill, I decide to keep it simple: four or five hefty but manageable cardboard boxes should do the trick.

As always, I start with the garbage piles. Back home with a good selection of empty cardboard boxes and a bag full of junk, I manufacture a few packages, which I seal with wide brown strapping tape, the kind that is crisscrossed internally by nylon fibers and cannot be torn by hand. I call Annie to admire the professional-looking result.

Suddenly, I have a nightmarish vision, a scene from those escape movies I'm so fond of: a uniformed guard approaches a group of prisoners pushing a cart, orders them to stop, and asks them to open one of their bundles; upon their refusal, he plunges in his bayonet.

“If they ask us, we have to be able to open the boxes and show what's inside!” I say, tearing open the boxes with a razor blade and pouring their contents back in the garbage bag. Annie shakes her head in disbelief at such idiotic paranoia.

When I share my worries with JP, and insist upon borrowing a dolly full of reams of Xerox paper from his store, he also thinks I'm ridiculous, but he complies. The new boxes I fashion and seal with regular tape satisfy me: they are guardproof.

Â

Twice I must push back the delivery date, because twice the Americans announce at the eleventh hour that they won't be able to make it.

Â

Finally it's the day. Definitely. A time of 1 p.m. is confirmed.

No. Donald calls, he'll be here at 2:00.

He calls again. Scratch that! Make it 2:30.

At 2:25, Chester calls. “Sorry, I won't make it before three-thirty.”

I know that Barry's office closes at 4:45.

Â

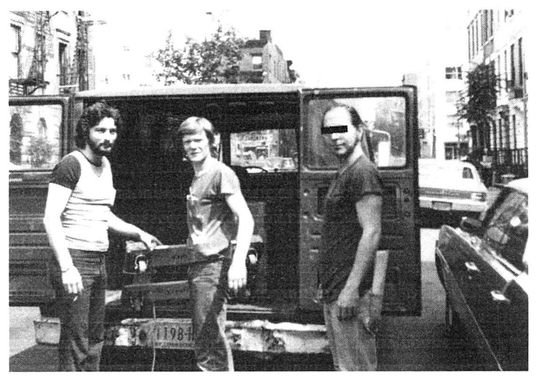

At 4:25 p.m., our rented van heads down the ramp beneath the towers. It's a world premiere! JP drives. Donald and I, seated on the floor in the back, will play underpaid delivery boys, languidly pushing our dollies. Chester, in the front seat, will act as the boss. Barry is at his desk on the 82nd floor of the south tower and will not move until we show up. His phone number is on our delivery slipâmodeled on a form from JP's storeâin case a security employee wishes to check with the recipient.

Â

In the security booth at the bottom of the ramp, the guard looks up from his newspaper and frowns in disdain at the paperwork JP shoves under his nose.

“Delivery, south tower,” announces JP, not gracing the man with a look.

The guard does not even answer, but points his chin toward a loading dock at the end of a tunnel.

When I get out of the van, I see the word POLICE written in large white letters, twenty feet away from me. So this is the famous precinct under the towers that I've heard so much about for so long.

There's only one problem: we can't use our dollies to unload. The floor of our van is lower than the loading dock. I'll have to check on that prior to renting a truck for the coup.

Â

JP slams the doors and drives away as planned, leaving Donald, Chester, and me with the boxes. Keeping my head down to avoid being recognized, I cannot observe the landscape as much as I want. Before I know it, we're in a freight elevator operated by a gum-chewing WTC employee who hears Chester say “Eighty-two!” and does not even bother to check our delivery papers.

The freight cage has no ceiling. Above my head, I watch each of the dim lights separating the floors pass me byâanother world premiereâand bite my lips, so not to reveal my huge smile.

Â

On the 82nd floor, we roll our merchandise to Barry's office. He signs our slips, does not so much as wink at meâI like thatâand with pride, like an extra on a movie shoot who's been granted his first line of dialogue, hands the papers back to Chester, saying with impeccable Shakespearean delivery, “There you go! Thank you. I'll take it from here.”

I seldom use the word “fun,” but this afternoon, it describes my mission. For once, I won't be covered in sweat, climbing for hours inside the towers; instead, festively dressed in white for a change, I stroll to the south tower lobby, open a forbidden door, and let gravity pull me down the stairs. Feeling carefree and innocentâI'm only looking for a bathroom, after allâI wander deep inside the basement's levels.

Â

Soon I find what I'm looking for.

Standing in front of the loading platform, I pull out my measuring tape. To my right, the door of the police station opens and the chief leans out. He lights a cigar and distractedly sets his eyes on me. No measuring tape today, let's go!

But not before a sudden instinct makes me lean forward and press my chest against the sharp edge of the platform. Waving at an imaginary fellow at the other end of the loading alley, I shout, “ ⦠and make sure you tell Pierre!” all the while discreetly rubbing my chest left and right against the edge to imprint a line onto my shirt.

Outside, I measure from the dirty line on my chest to the bottom of my shoes: 4 feet exactly.

Â

Back home, while I repeatedly wash the white shirt, unable to completely erase its grease-and-rust mark, the perfectionist in me can't help critiquing the choice of the name Pierre. Joe or Charlie would have been better.

A postcard with two lines, a thirty-second phone callâsince Jean-Louis's departure, I have been informing him of the ups and downs of the coup, but today I start a long letter. Today, once and for all, I decide when to walk.

Flipping through my French datebook, which lists the saints' days, I notice I have already moved the date eleven times. I erase the latest entry, August 1, as boring and too soon. I like the seventh, it has a ring to it. The day beforeâwhen we'll be sneaking in with the equipmentâreads: “Mardi 6 Aout 1974, Transfiguration.” I do not know what the name means in the iconography of Christianity, yet when I imagine entering the dark viscera of WTC, emerging from its crown, hanging a wire in total darkness, and, sometime later, appearing flooded with light, balanced atop the world, I find

transfiguration

a fitting epithet.

transfiguration

a fitting epithet.

“The walk is August 7, in exactly three weeks ⦠,” the letter begins.

Â

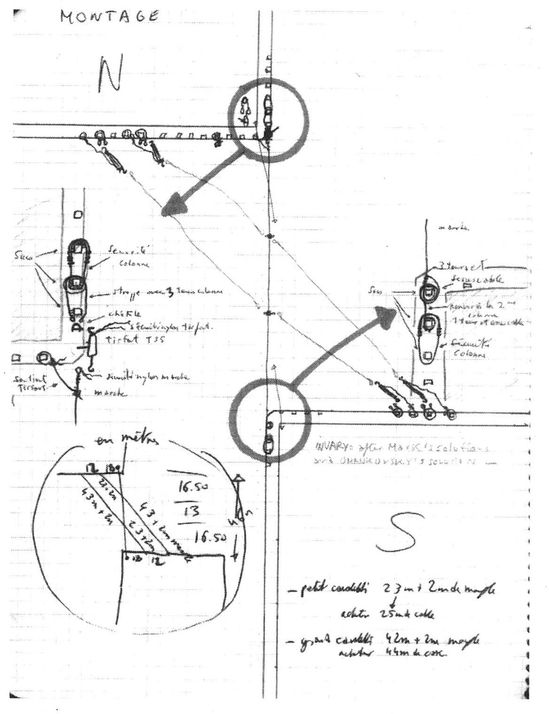

The outcome of the false delivery; the fact that Barry found a large hiding place on his floor for men and equipment; the evidence that such a place must exist on the 82nd floor of the other tower; the simplicity of hiding there until nightfall, of using the stairs to hoist peacefully, one floor at a time, half a ton of equipment to the roofâall the heavy stuff goes with me in the south tower ⦠Everything, I write everything to Jean-Louis.

Following the main lines of the new plan, I cover every detail of the rigging. I note each move Jean-Louis will have to make. I draw each knot he'll have to tie. I list every tool he'll need.

In conclusion, I compose a French-English lexicon of useful terms and advise my friend to copy it onto an index card he'll slip into his pocket. That way, he'll be able to communicate with his American accomplice.

The letter runs to twenty-one pages; it takes me four days.

I reread the missive again and again, each time adding details and sketches and making corrections.

Before I lick the envelope, I can't resist going through the letter one last time. I'm particularly fond of the lexicon, which, besides

pull, push, lift, over there, right here

, also translates,

Be careful, it's going to slide! Hold on, be quiet, I heard something!

and, in an eerie premonition,

Don't give up!

pull, push, lift, over there, right here

, also translates,

Be careful, it's going to slide! Hold on, be quiet, I heard something!

and, in an eerie premonition,

Don't give up!

Â

Four days without sticking my nose out of the house, four days reduced to eating yogurt and smelling the cat piss of Annie's protégés!

Other books

Stockholm Surrender by Harlem, Lily

These Delights by Sara Seale

Bone Deep by Webb, Debra

Summer Harbor by Susan Wilson

Pretense by Lori Wick

The Girls by Helen Yglesias

A Murderous Procession by Ariana Franklin

Veganomicon: The Ultimate Vegan Cookbook by Isa Chandra Moskowitz, Terry Hope Romero

Under the Dusty Moon by Suzanne Sutherland

F Paul Wilson - LaNague 02 by Wheels Within Wheels (v5.0)