To Reach the Clouds (4 page)

Read To Reach the Clouds Online

Authors: Philippe Petit

The moment I set foot on American soil, a somber customs agent singles me out from the line, tells me to drag my suitcase to a table in the corner, and orders, “Open up!”

Â

The first item under scrutiny is a canvas pouch the size of a shoebox.

The inspector pulls out decks of playing cardsâsome blank, some made up of fifty-two tens of clubsâfake fingers, double-headed coins, make-believe burning cigarettes with glowing ashes at the tip. Exhausted by a sleepless flight, not in the mood to play the magician, I wait for the old man's question.

No question.

Instead, the officer grabs an ordinary deck and spreads it into an impeccable fan, which he thrusts at my chest, barking, “Take a card, any card!” An amateur illusionist welcomes a fellow criminal to the shores of his future crime. Joyful omen!

A line of passengers has formed behind me, waiting to be

searched. Absorbed by his routine, the prestidigitator merely shrugs and, hardly looking up from the silver dollar he is about to vanish, shouts, “Hey, Jack, take those people, will ya? Don't you see I'm busy here?”

searched. Absorbed by his routine, the prestidigitator merely shrugs and, hardly looking up from the silver dollar he is about to vanish, shouts, “Hey, Jack, take those people, will ya? Don't you see I'm busy here?”

Â

And so it goesâ“Do you know this flourish?” “What about this one?” “Oh, can you do that again?”âwhile above our heads flags of all nations flutter in the air-conditioning ⦠or is it the Babelesque brouhaha?

By dawn, as if waiting for a friend, I stand post outside the revolving doors that give entrance to the cathedral hall of one tower.

Soon the first construction workers appear. I jot down what they wear, the color of their helmets, what tools dangle from their belts, the supplies they carry, the equipment they dolly in.

Then the office workers start arriving. I pay attention to the routes they take. Why do some pack themselves beyond the point of safety into an elevator while other cars remain empty? Why do certain employees detour to a temporary guard booth to flash an I.D. card?

It's now rush hour: the crowd thickens; lines start forming at the newsstand. Like blood in an artery, the flow of human lives keeps pouring through the halls, pulsating:

Stop, go. Stop! Go, go, go!

The sleepy murmur of early arrivals mounts to bustling clamor. There is yelling. There is shouting. Doors slam. People bump into each other. People run. Frequently, someone waves above the sea of heads to greet a fellow employee recognized in the distance.

Stop, go. Stop! Go, go, go!

The sleepy murmur of early arrivals mounts to bustling clamor. There is yelling. There is shouting. Doors slam. People bump into each other. People run. Frequently, someone waves above the sea of heads to greet a fellow employee recognized in the distance.

I spot an imaginary friend about to step into an elevator, “Paul! Paul! Wait!” I run after the phantom, brushing by the guards, stepping on toes. Too late! The doors just close in front of me. Minutes later I try again. “Hey, John! John!” I'm not boarding the elevator. I'm just practicing.

By late morning the site calms down; the crowd dissipates. It's pleasantly quiet.

Â

Finally lunchtime arrives: security personnel relax, businessmen roll up their sleeves and loosen their ties, everyone is hungry, no one cares; the buzz rises to a joyful roar. The multitude is back.

That's when I enter.

Jumping from elevator to elevator, I always manage to reach a higher floor; trying staircase after staircase, I always succeed in ending up on the rooftopâinvariably, lunch break ensures it's deserted.

My clandestine visits become daily affairs.

I specialize in lunchtime!

Each attempt makes me smarter at steering clear of the guards, more efficient at dealing with surprise encounters, at avoiding construction foremen. Although I still get lost and get chased, sometimes I feel I'm mapping out the skeleton of an itinerary.

Once on the roof, I proceed with an inventory of the equipment I could use for the rigging. I locate hiding places, I check possible anchor points. Often, Jim Moore joins me, his cameras cautiously recording it all. When our rooftop clamors back to construction racket, we head down to the streetsâalways an easier exercise than getting to the roof.

Â

In the early afternoon, improvising a disguise, I impersonate a homeless drunk whose territory is an inclined sidewalk by a ramp

I recently discovered: a ramp leading under the towers, a ramp constantly used by delivery vans and the giant trucks of moving companies.

I recently discovered: a ramp leading under the towers, a ramp constantly used by delivery vans and the giant trucks of moving companies.

On a tiny pad, I record discreetly the time of entry and exit of each vehicle as well as what's painted on itâa company name, a telephone number, a logo. I note the driver's uniform. I count the passengers. When a police car uses the rampâwhich is often, there must be a police station undergroundâI slouch down, offering less of my vagabond silhouette.

Â

Then it is time to run back to the revolving doors, so as not to miss the exodus of steel workers, electricians, painters, and contractors of all trades, done with their day's work. More observations, more notes.

Â

Soon thereafter I make sure I catch the first businessmen going home. I usually remain until the crowd grows into an out-of-control stampede, until thousands of employees, now tired, now silent, rush out shoulder to shoulder like buffalo fleeing a burning prairie. Actually, they remind me of a scene from

How the West Was Won

.

How the West Was Won

.

Sometimes an office worker will turn suddenly and disappear back into the tower, apparently having forgotten something on his desk. Great, I can use that later.

I watch for an hour as the ground vibrates, and then they are gone.

Â

In the evening, I go back. I dare to approach the I.D. desks where visitors must check in; I glance at the logbook when the guard is not looking. I roam around hallways and tunnels, trying not to look suspicious: I must understand how the security works. Why so many different types of guards? How often do the police show up? Some floors stay lit all nightâwhy? Are the offices empty, are people still working up there?

Â

Day after day, again and again, I follow the same routine. And I never get caught.

For a long time, I visit only the north tower. It simply doesn't occur to me to spread my scouting trips evenly between the towers. In fact, I don't even realize it is the north tower I keep visiting. It just happens to be the first tower I reach when I come out of my usual subway exit and enter the temporary tunnel that gives access to both towers.

Only later, when I create a map of the area with all the WTC buildings (existing or soon to be built) and the surrounding streets, do I begin to differentiate between the north and south towers, and to refer to them with the architect's original titles: WTC I/tower A (north) and WTC II/tower B (south). And only later still do I learn that the north tower was the first to rise from the ground and the first to reach completion.

“Me? Peter Smith.”

I find out that the names written down in the heliport register are kept only to alert the families of crash victims. Fine by me.

Â

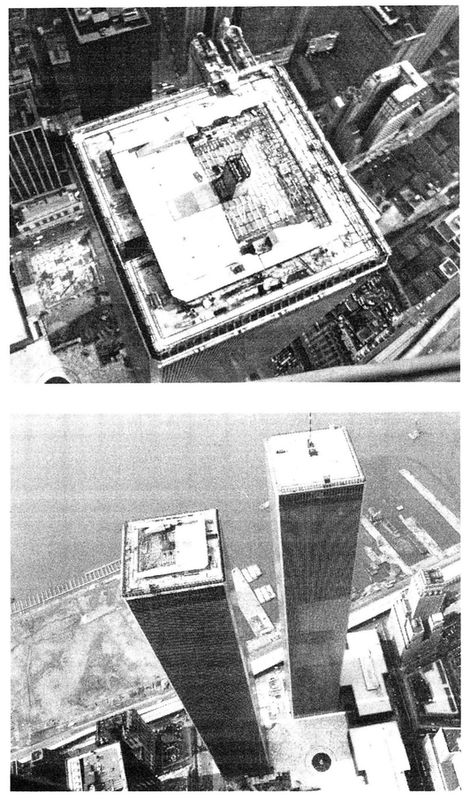

Jim, all larded up with color film, makes himself comfortable inside the helicopter while I nail the pilot to the ground. “We'll start with a sweeping pass, high and far away from the towers, so that my photographer gets his establishing shots. Then we'll move a bit closer: I want a profile view of each tower at its full height. After that, I need to hover, exactly centered, above each roof but not too highâI'll tell you. We'll finish with a stationary flight between the two rooftops, right in the middleâ”

“Oh, I can't do that. FAA regulations won't allowâ”

“Well, then, you'll climb to two thousand feet along the vertical axis marking the center of the space between the two towers, very slowly if you can ⦔

I wanted to bring the aircraft where my wire will hang one day, so that I could record the vision I will have in the middle of my walk. Instead, I will have to content myself with staring down at

the two summits from above. It may be that once on the wire between these summits, the distance separating me from the ground will appear less grandiose. That's what I want to believe. But mind and eye are capricious accomplices.

the two summits from above. It may be that once on the wire between these summits, the distance separating me from the ground will appear less grandiose. That's what I want to believe. But mind and eye are capricious accomplices.

Â

As the machine extracts itself thunderously from the concrete pad, my elation knows no bounds. We climb. We slide, glide, twirl. Visibility is 100 percent.

We dance a farandole around WTC as I laugh with pleasure.

Alas, the pilot does not manage to approach the facades as closely as I want. I complain! He glances out of the corner of his eye at this very demanding tourist. But turbulence caused by the enormous mass of air rushing through the funnel between the towers makes the helicopter vibrate more at each attempt. “Damn currents ⦠always at that spot,” the pilot mutters.

I know he is absolutely wrong! I am certain my brother the wind softens at times, just to admire a wirewalker passing by; and yes, I'll watch out when he applauds!

Â

Our fifteen minutes are up.

12.25 meters? No way. A mistake in the conversion of feet to meters? 400 meters? Can't be. In the darkness, did I misplace the decimal point? 200 meters? Shit. I must have forgotten to bring the counter back to zero again.

I have to rent the surveyor's measuring wheel on three different occasions to get it right: 42.06 meters, 138 feet. Definitely.

Ah, finally I can return the stupid machine to the rude, suspicious hardware-store owner on Canal Street and get my extravagant cash deposit back.

Â

Having just learned what I think is the exact distance between the two towers, I add to it my rough estimation of the horizontal

distance separating the upper edge from the lower ledge on each roof and come up with, give or take, 50 meters. The space needed to anchor the cable on both sides brings that figure to, hmm ⦠56 meters.

distance separating the upper edge from the lower ledge on each roof and come up with, give or take, 50 meters. The space needed to anchor the cable on both sides brings that figure to, hmm ⦠56 meters.

Plus a few meters of unknown.

I decide to call it 60 meters, say 200 feet.

Â

Really, that much?

It stands for “isolated occurence.”

That's what anthropologists, in their reports, call any atypical finding in the field.

Â

It does not happen often. But today it did. I was rushing up the stairs on the upper floors of the south tower ⦠Or was I rushing down? ⦠Or was it the north tower? No matter! There was an earthquake.

Well, not really an earthquakeâa shake. Inside me.

I stopped and held on to the railing: Was my heart failing me?

Â

Within half a second, the metal steps started quivering beneath my feet. Then, under each of my hands, the rails started vibrating ever so slightly. No, not so slightly. The steps, the railings, my body transmitted their trembling to the stairwell partitions directly around me. And soon, far above me, far under me, the walls, the entire building started shivering, lights flickering.

Through the masonry came the cry of the tower: its steel structure being lengthened and shortened, twisted and squeezed, it let go a plaint of pain. As if guilty of having expressed secret feelings, instantly the tower went totally quiet and totally still.

Â

The swaying of the building must be felt tenfold on the top.

I refuse to imagine what that could do to me on the wire.

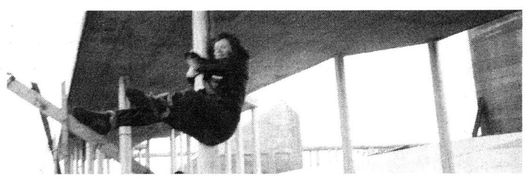

Look! Jim even took a picture!

The other day, it was windy in the streets.

We arrived on the roof and met a hurricane.

I tried to breathe without a hand covering my nose. I couldn't.

I tried to walk erect without holding on to something. I couldn't.

For fun I embraced a column and let my body be lifted horizontally. Look!

I refuse to think such wind could happen when I walk.

Â

Last week, coming out of the subway, I looked up at my towers and couldn't see past the 78th floors because a thick fog was playing magician, vanishing the upper floors and the roofs for hours.

What if I had been walking the wire at that time?

And went back down and told everyone? And everyone would reply, “Sure you did!”

Â

Usually, an I.O. is not taken too seriously by field scouts, who sometimes bury it in a report, or even omit it.

Other books

Night Things: A Novel of Supernatural Terror by Talbot, Michael

Magic Rising by Camilla Chafer

Quality Assurance by Dragon, Cheryl

DARK COUNTY by Kit Tinsley

Snake Eyes (9781101552469) by Sherman, Jory

The Reanimates (Book 2): The Highway by Rudolph, J.

Invitation to Seduction: Open Invitation, Book 1 by Haynes, Jasmine, Skully, Jennifer

Mystery by Jonathan Kellerman

Marriage by Mail (Grace Church Book 1) by Jan Holly

Friends by Charles Hackenberry