To Reach the Clouds (2 page)

Read To Reach the Clouds Online

Authors: Philippe Petit

During the next few years, unbeknownst to me and thousands of miles away, something amazing, something unheard of, something colossal is happening.

First an architect had a vision. A preliminary model, eight feet high, was constructed; another dozen, at different scales, would follow. Little sketches gave way to drawings of great detail and dimension, thousands of them. In downtown Manhattan, thirteen city blocks would have to be cleared. Ground was broken:

Â

Now imagine!

Hundreds of men, trusting only those childish cardboard-and-glue assemblies, guided only by those pitiful sheets of flammable paper marked with thin blue lines, hundreds of men are leading thousands of men, men with tools, men with machines, into stacking steel, concrete, aluminum, and glass in perfect balance and in total disregard of the commandment, “Thou shall not try to reach the clouds.”

Â

The ants are building a skyscraperâa skyscraper with two arms, pointing at the gods.

The rest is noise, lots of noise. The cranes are slewing, luffing, and lifting 192,000 tons of steel. Each I-beam, each load-bearing column tree, each truss is numbered by hand before being slung and sent into the sky. And someone always knows precisely how and when to connect the pieces.

This goes on for three years.

Â

And the twin towers rise.

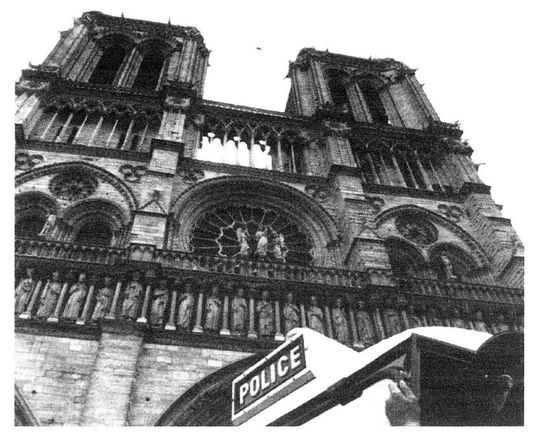

Because I live on rue Laplace, the towers of the nearby cathedral watch me come and go every day. One afternoon they call to me.

Â

I take a few measurements in secret, inspect areas not open to tourists, plan a nocturnal rigging, convince a few friends to become accomplices.

Â

Paris is asleep.

My false key allows us to reach the top of the towers. One of my juggling balls, tied to a fishing line, is thrown across. We install the steel cable all night.

Â

Â

Paris is awake.

I promenade and daydream 250 feet in the air on this twenty-sixth of June, 1971âmy first illegal aerial performance.

The romantic escapade ends up on front pages everywhere; the world salutes the valiant young poet. Except the French, who are not touched, not enthused. They do not need an encore.

Â

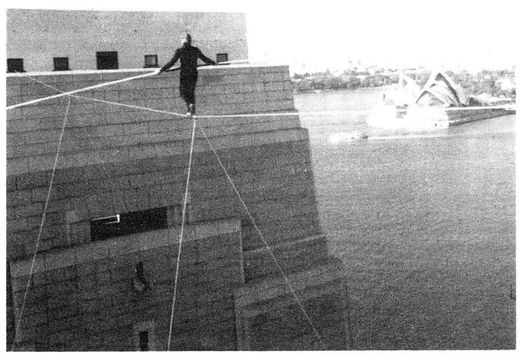

Disgusted, I depart for Australia. In Sydney, I improvise another surprise, a walk between the northern pylons of the world's largest steel arch bridge, on the third of June, 1973.

Â

Without these first clandestine walks, would I have reached inside the red box for a more formidable opponent?

Sometime between Notre-Dame and Sydney Harbour Bridge, an alarming article appears, tucked away in the back of a magazine. It tells of two pillars already towering above lower Manhattan. A full-page aerial shot portrays the towers as if they were already out of reach. I can hear the cranes bustling to complete the structure on schedule. I can smell the smoke, feel the incessant activity, the urgency â¦

The article is so disturbing that I throw it into the large red box labeled PROJECTS and try to forget about it.

I cannot.

Â

The towers keep erupting in my conversations, my thoughts, my dreams.

How were they born without warning?

Why didn't I hear the town crier shouting the news on rue Laplace: “The towers are being built! The towers are being built!”

What if they are completed before I link them for eternity? I must keep an eye on them. Once they are officially opened, it may be impossible to take them by surprise.

Â

Alarming, indeed.

I'm tired of the French. The zeal of the Parisian police and the constant wet and cold have curtailed my street performances so drastically that I decide to try New York City. Am I being influenced by my new, first-time-in-Paris American girlfriends, adorable Jessica and her suave companion, Ann? After each of my juggling circles, they tell me, “No one does that in New York, they'll love you over there!” Or is it the offer Ann whispers as she heads back to the States, to share her East 96th Street apartment?

January 6, 1974, I pack my bags and go up to the roof to scream, “I'm going to America!”

I have locked up my room at rue Laplace and am almost downstairs when I suddenly run back up. From under the bed I pull out the red box and retrieve the skyscraper clippings. You never know â¦

Two hours later, I board the plane with my top hat on and my antique postal bag over my shoulder, pushing my unicycle.

Â

It's even colder in New York.

Who cares? I'm delighted to be able to juggle under a new sky, in front of new people.

The first circle of chalk I draw on Manhattan asphalt is between Patience and Fortitude, the stone lions trying to pass for sphinxes on the front steps of the public library. And the first spectator to throw a buck into my hat is ⦠Francis Brunn, the

greatest juggler of all time, my friend! “But I thought you were in Barcelona!” We hug, we laugh. We meet only by accident, by miracle.

greatest juggler of all time, my friend! “But I thought you were in Barcelona!” We hug, we laugh. We meet only by accident, by miracle.

Several other people in the crowd approach me. I remember the warm handshake of a muscular young man standing very straight, like a dancer: Jim Moore, mime-photographer. We promise to meet again.

I persuade Francis to stroll with me in the snow. We have so many stories to trade. I let him know I already adore this frightening metropolis, and I confess, “One day New York will be mine! I'll string a wire somewhere between the tallest buildings and I

will become the. king of the American sky!” He believes me, I know; his laughter proves it.

will become the. king of the American sky!” He believes me, I know; his laughter proves it.

Â

The next evening after street-juggling, I return to 59 East 96th Street to find a huge cockroach in the kitchenânever heard of them in Paris, never met one before! I record in my datebook my first impression of New York: “It's old, it's dirty, it's full of skyscrapers. I love it.”

With performances, my new friends, and my appetite to devour Manhattan, I keep forgetting the towers' existence. Nearly three weeks later, just days before I am to return to France, I force myself to go meet them. Since I'm far up the immense oblong island, and they happen to live near the bottom, the price of the encounter is a forty-five-minute subterranean journey.

Without warning, at five o'clock on the afternoon of the corrida, the bull is let out of the dark cell where he has been confined without food for days. Enraged, he springs onto unknown sand, eager to fight, only to find scorching sun above, and screaming voices. He is blind. He is alone. He is lost. He is scared. There is no such thing as an enemyless bullfighting arena in the multitude of memories stored in him. It does not exist. Neither does the novel sense of being powerless, of having the world against him.

Â

That is how I feel, emerging from the subway station at the foot of the World Trade Center, after my prolonged underground ride. The volume of the towers, their size, screams one word at me, etches it into my skin as I pause atop the stairs, holding on to the railing:

Impossible

!

Impossible

!

I cannot breathe. Cannot move, talk, think. I am dismayed, my dream dissolved. I feel fear. Glued to the railing, I am an invalid. I stare, I look, I glance, I observe, I watch. My scrutiny yields only two monoliths, beyond all scale, and carves deeper into me the word:

Impossible!

Impossible!

Defeated, disgusted, I am about to retreat, but the bold capital U of the towers changes into a powerful horseshoe magnet of gargantuan proportions that draws me nearer its footing.

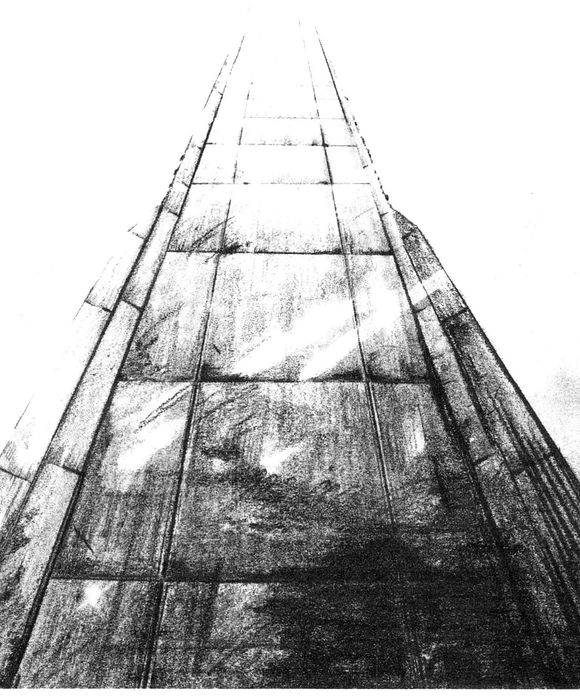

Avoiding the guards, I trespass onto the plaza, which is still under construction. I reach one of the towers. Facing a corner, I position myself an inch away from the seven-foot-wide metallic face. At my feet, the connection between vertical aluminum panel and horizontal concrete slab is flawless, but surely the wall does not start where I stand. It must surge from the entrails of the earth.

I press my chin against the cold aluminum, forcing my eyes upward, in search of the end of the wall. There is no end. This wall has no top. Instead, it becomes skyâaluminum into azure!

Â

I lie against this narrow strip of unknown land, looking up, until I comprehend: it is a landing field for extraterrestrial vessels. No! A takeoff field: the clouds give it directionâa limitless runway into heaven. It is definitely not man-made, nor of any use to us humans. So uncertain is its lengthâcall it heightâand so alien its design, the dreaded word has now infiltrated my heart:

Impossible! Impossible! Impossible

! it pounds. I can no longer breathe.

Impossible! Impossible! Impossible

! it pounds. I can no longer breathe.

A very cold chin calls me back to reality. I lower my tired eyes to the ground and glance at the base of the other tower, as if it would be useful to figure the distance between the two corners. It is not. The merest attempt at estimating, the slightest unconscious recording, is shrugged off as an absurd association with some never-to-be-realized dream ⦠as an exercise in futility.

Â

I long to flee, but still the colossal magnet controls my destiny. I find myself approaching the other tower, discovering an exit door left ajar, sneaking inside a narrow path, ducking under a “No Trespassing” chain, running up some emergency stairs, jumping inside an elevator, going up, going down, getting lost, avoiding

guards. I find a safe staircase and climb as fast as I can, passing floors occupied by offices noisy with activity. As I continue to climb, the offices become silent, then vacant. Then the floors lose their partitions. Now I can see windows all around me; there are no more walls. I am high in the sky. Each floor I climb looks more like a construction site. I bump into construction workers as my body language declares, “What are you looking at? I'm the owner of these buildings!”

guards. I find a safe staircase and climb as fast as I can, passing floors occupied by offices noisy with activity. As I continue to climb, the offices become silent, then vacant. Then the floors lose their partitions. Now I can see windows all around me; there are no more walls. I am high in the sky. Each floor I climb looks more like a construction site. I bump into construction workers as my body language declares, “What are you looking at? I'm the owner of these buildings!”

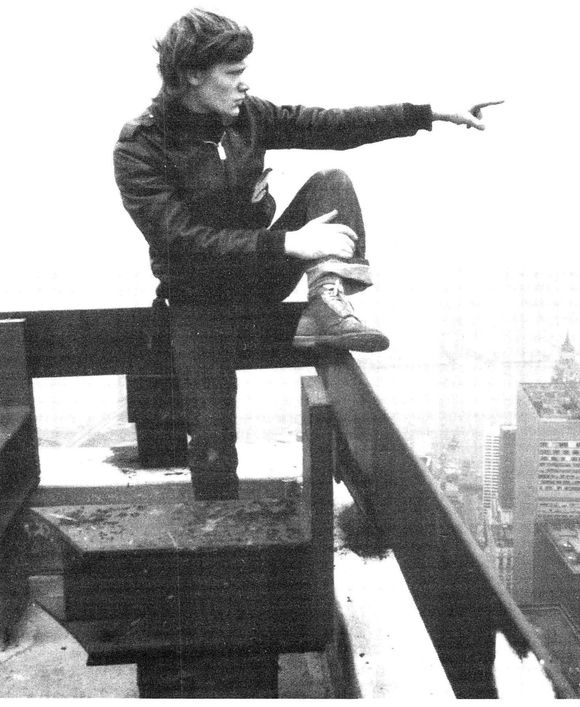

I've been running upwards for an hour when I taste the summit's fresh air, seeping through a forest of structural steel. With a little help from heaven, out of breath and unchallenged, I manage to pass my head through an opening to the rooftop.

Â

My tiny staircase pierces the roof near its center. I stay a moment sheltered below the penultimate step, halfway through the trapdoor, lost in contemplation. There is a huge red crane by my side, and behind me an enormous rusty I-beam contraption to support an antenna. Around me spreads the naked platform, a mistake amid the clouds. I step out onto the rooftop. No railingâif I run, I'll finish my course in thin air, changed into a bird. The roof is deserted. Despite its immensity, its exposure on all sides renders it tiny, almost fragile. It's an indestructible aerie, a fortress at the mercy of the next gust.

The city has vanished, the world is no longer in motion, humanity has ceased to exist. There is no notion of “around,” no “over there,” certainly no “below.” The union of altitude and solitude fills me with an arrogant sense of ownership. After all, the sky is my domain.

Â

Unsure this isn't just a dream, yet conscious of my vulnerable position and not wanting to impose unnecessary vibrations from my weight in motion, I tiptoeâcarefully, yesâto the corner facing the other tower.

There! Another floating slab! So near, yet a continent apart. And that's when I see the word stretched across the gap between rooftops in all its obscene syllabic obesity:

Imâposâsiâble!

Moving my head left to right like a child in the first grade, I read it and read it and read it. Then I lean over the edge, ready to climb down the inclined columns to the six-inch ledge eleven feet below that connects the 110th floor with 1,350 feet of verticality, so I can look straight down. I do not. Because that's when it strikes me: teeth clenched, eyes half closed, in horror, in delight, I manage to whisper my first thought (whisper, so the demons won't hear): “I know it's impossible. But I know I'll do it!”

Imâposâsiâble!

Moving my head left to right like a child in the first grade, I read it and read it and read it. Then I lean over the edge, ready to climb down the inclined columns to the six-inch ledge eleven feet below that connects the 110th floor with 1,350 feet of verticality, so I can look straight down. I do not. Because that's when it strikes me: teeth clenched, eyes half closed, in horror, in delight, I manage to whisper my first thought (whisper, so the demons won't hear): “I know it's impossible. But I know I'll do it!”

At that instant, the towers become “my towers.”

As I run downstairs like a thief, careful to avoid capture, it dawns on me: I had not dared to reach the ledge, had not risked looking down. It was enough to look across.

Â

Once on the street, a new thought:

Impossible, yes, so let's get to work.

Impossible, yes, so let's get to work.

Other books

Dr. Horatio vs. the Six-Toed Cat by Virginia Smith

Church of Sin (The Ether Book 1) by James Costall

The Dead Girls of Hysteria Hall by Katie Alender

Foretold by Rinda Elliott

The No Cry Nap Solution by Elizabeth Pantley

Cursed by Wendy Owens

Aurator, The by KROPF, M.A.

Moving Water by Kelso, Sylvia

OBSESSION (The Bening Files (Novella) Book 4) by Trautmiller, Rachel