To Reach the Clouds (5 page)

Read To Reach the Clouds Online

Authors: Philippe Petit

A large rusty nail by the plaza's construction site punctures my right foot as I carry out my daily rounds.

I roll on the ground, more in rage than in pain: Aah, how stupid! There goes my research! There goes the entire coup!

I end up in bed with a pachyderm's ankle, thinking about the fog, the swaying, the wind, and everything else that can transform

the coup into a failure. I play chess with friends, but in between turns, I see my rooks becoming twin towers, and after each defeat, my excuse is the same: “Oh, I was thinking about WTC!”

the coup into a failure. I play chess with friends, but in between turns, I see my rooks becoming twin towers, and after each defeat, my excuse is the same: “Oh, I was thinking about WTC!”

After a day and a half of immobility, I still can't put any weight on my foot, but I'm leaving soon for Paris, so, holding on to Ann's shoulder, I hop to the pharmacy at the corner of 96th Street and Madison Avenue to buy a pair of crutches.

Limping and hopping, I drag my sweaty, sorry self back to the towers.

Â

A miracle!

A lame guy on crutches passes everywhere. People hold doors open for him, press elevator buttons for him, ask him all day long, “You okay?”

Yeah, I'm okay, all right!

Without hurrying, I venture into sensitive staircases. Without hiding, I explore dangerous floors. Mistakenly, I open a dozen forbidden doors. Here and there, at strategic places, I sit down to catch my breath, leaning my tired wrists atop propped crutchesâno one could invent a more natural attitudeâand let my eyes scan the scene. That's how I manage to learn the code above the doorknob of the security gateway that has been resisting me for days: today, several employees punch in 7-7-4-3-5 three feet from me, without so much as a suspicious glance. Whenever a guard surprises me, my infirmity transforms him into a Samaritan who escorts the lost soul all the way to the exit.

The crutchesâa trick to remember.

Â

Two days later, when I am able to limp around freely, again I grab the sticks for an improvised premiere: a middle-of the-night sneak scouting.

It's not easy to get a cab to WTC on 96th Street at 3 a.m. on a rainy Saturday. Two drivers refuse to take me when they learn where I am goingâ“No one lives down there”âbut a third driver does not ask questions, does not say anything, although he stares at me in his rearview mirror at each red light.

Â

The door slams; the taxi speeds away.

I am facing the unfinished commuter tunnel that drills beneath the construction site to reach the underground entrance to both towers. In the rain and dimness it looks like a gigantic black mouth. At my back, a freezing draft whirls across the deserted avenue. Above me, the March wind howls. The towers, mostly darkâhow rareâloom before me like a vampire's castle. My trembling silhouette proceeds through the tunnel.

Through the glass panels of the north tower's lobby, I can see the guard at his desk, leaning half asleep on the logbook I know well.

I pace back and forth in the shadows for an hour, drenched and frozen, before I decide to risk the wolf's den.

I hobble through the revolving glass door, reach the desk, lean my crutches against it, nonchalantly pick up the ballpoint pen, and copy the last entry. I give the guard a little wave and direct myself, light-footed, toward the nearest elevator.

Shit! My crutches!

I turn about with a smile, hop back to the desk, pick up the crutches, and disappear like a true handicapped man.

The guard does not react.

Â

Several times during the night, I have to run back downstairs to retrieve the crutches forgotten on the floor where I wasâoh so successfullyâscribbling my spy plans.

The day before my departure, Jim comes up into the south tower with me. We climb the stairs silently, so as not to attract the attention of the sentinels stationed on the 44th and 78th skylobby landings. At some point we hear a guard descending quickly toward us, walkie-talkie blasting. We have no time to retreat, no place to hide. My reflex is to test my two-people-passing-in-front-of-someone-whose-job-it-is-to-arrest-them hypothesis, which states: Do not slow down. Disregard the hostile presence to the point of

not acknowledging itâbumping is allowed. Draw your accomplice into a mammoth festival of laughterâtears in your eyes, as out of control and loud as possible: if you're good, the enemy may join in. Conversely, engage your co-conspirator in a verbal battle in apparent full swing, each of you roaring your differences on the subject at hand, spit flying, gesticulating angrily; if you act your parts well, your true antagonist may step aside to let you pass.

not acknowledging itâbumping is allowed. Draw your accomplice into a mammoth festival of laughterâtears in your eyes, as out of control and loud as possible: if you're good, the enemy may join in. Conversely, engage your co-conspirator in a verbal battle in apparent full swing, each of you roaring your differences on the subject at hand, spit flying, gesticulating angrily; if you act your parts well, your true antagonist may step aside to let you pass.

With no time to warn Jim, I go for the loud argument:

“What the hell do you mean, Tuesday? You told Gerard Tuesday? Are you crazy? Everything is arranged for Wednesday! You're such an idiot! You really said Tuesday? Answer me!”

“Tu-tuesday?” stutters Jim. But immediately he gets it and jumps into the improvisation.

Screaming at each other, we pass.

Â

Closer to the roof, before we reach the floors still under construction, we give ourselves a well-deserved break to celebrate our victory, dry the sweat from our foreheads, and gather our

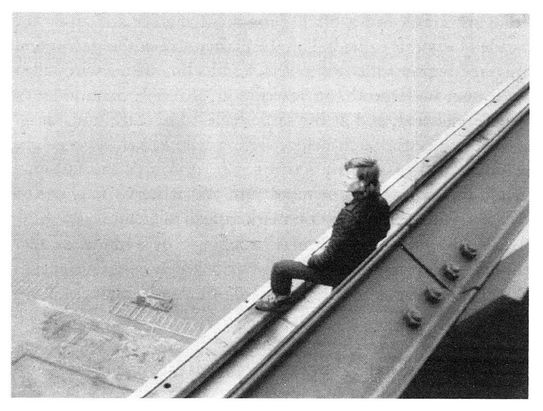

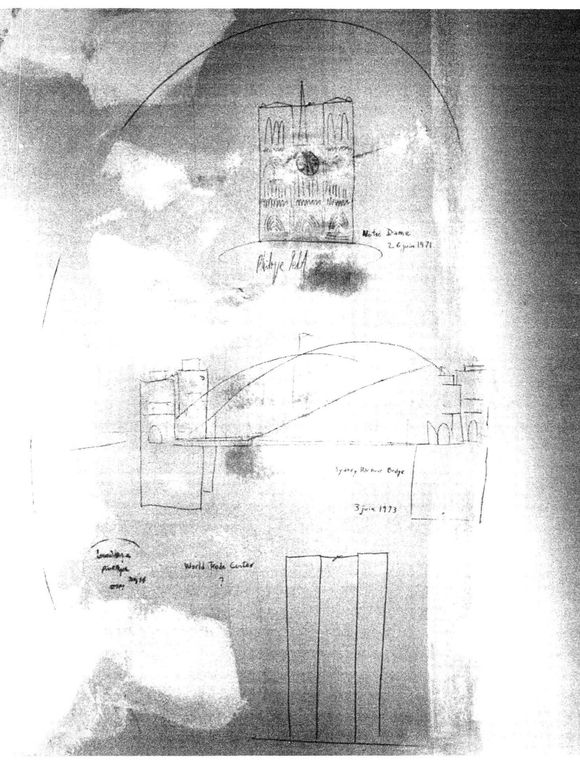

thoughts. I pull out a black permanent marker and draw the facade of a gothic cathedral on the plaster wall of the stairwell, at eye level. Between the two towers, I add a line with a wirewalker on it and, underneath, an inscription: NOTRE DAME, 26 JUIN 1971. Under that, and at the same scaleâtherefore much largerâI draw a steel arch bridge with a wirewalker between the pylons: SYDNEY HARBOUR BRIDGE, 3 JUIN 1973. At the bottom, I sketch the twin towers of my dream and write WORLD TRADE CENTER, with a bold question mark instead of a date.

thoughts. I pull out a black permanent marker and draw the facade of a gothic cathedral on the plaster wall of the stairwell, at eye level. Between the two towers, I add a line with a wirewalker on it and, underneath, an inscription: NOTRE DAME, 26 JUIN 1971. Under that, and at the same scaleâtherefore much largerâI draw a steel arch bridge with a wirewalker between the pylons: SYDNEY HARBOUR BRIDGE, 3 JUIN 1973. At the bottom, I sketch the twin towers of my dream and write WORLD TRADE CENTER, with a bold question mark instead of a date.

I enclose the three drawings in a single oval frame, so they appear as an ensemble, which I sign quite legibly, PHILIPPE PETIT.

Unbeknownst to me, this romantic fresco will almost kill the coup.

Â

On the roof, Jim quickly takes the shots that are missing from my collection and rushes back down to the lab so I'll have the slides before my flight tomorrow. On his way down, he adds to the fresco a misspelled but loving “goodbye Phillipe.”

What a pity my new friend, who has been so helpful, encouraging, and enthusiastic, who has taken great pictures instrumental to the coup, refuses to be part of the rigging crew on D day. I tried to convince him, to no avail. He will give all the help I want in and around the towers, but not up there on the day of the coup.

He has his reasons.

Â

I stay for hours at the top, making a final technical inspection. Jean-Louis's intuition is confirmed: the equipment I need for a safe rigging can't be chosen from what clutters the roofs. I'll have to bring my own gear.

My work is interrupted regularly by prolonged stares at the other roof, by forgetful gazes at the void.

Â

Suspended between the tangible and the ephemeral, I find myself pondering: Would anyone but a crazed bicephalous being, half engineer, half poet, willingly shackle himself to a venture of such magnitude? I am prisoner of my dream.

Compared to the ad-lib observations and the bits of knowledge I gathered during my first visit to America, the intelligence I have recently collected, along with all the sketches, measurements, and photographs, constitutes a professional study addressing most of the project's concerns. Or so I convince myself.

Â

Everything finds its place inside a thin, spiral-bound high school notebook, 81/2 by 11 inches, its title written in longhand: “WTC Organization.”

Nothing fancy. A tool.

The first WTC

cahier

is born. And thickens.

cahier

is born. And thickens.

Â

For example, today I enter:

Saturday, March 9, 1974. Back to Paris.

If my prediction is correct, the coup should happen mid-June, say Sunday, June 16. The next day in case of bad weather.

Ill-fated.

That's how I feel after I miss my flight because it fails to appear on the electronic screen at the airport. The next plane to Paris is tomorrow. I vehemently demand a three-star hotel; I'm given a deck chair in an abandoned back room supposedly reserved for flight attendants. In the turmoil, I realize, I left my pocketbook in front of the screen. I run back: of course it's gone. I don't care about the money, but it was full of notes and ideas waiting to be copied into the WTC cahier. I search frantically for hours and interrogate virtually every human being in the terminal, then go back to my den and fall asleep in despair. In the middle of the night, a black giant in uniform points his flashlight, then his stick

at me when I refuse to follow his order to leave. He states that I have no right to be in this part of the airport. I claim I do. He points his gun at me. I smile. “If you want me out of here, you'll have to kill me, then drag the body.”

at me when I refuse to follow his order to leave. He states that I have no right to be in this part of the airport. I claim I do. He points his gun at me. I smile. “If you want me out of here, you'll have to kill me, then drag the body.”

The giant leaves.

Â

To me, this disastrous departure day is an omen.

I find a telephone, hide under a desk, and spend most of the night figuring out the code to obtain an outside line. I call Ann and share with her my misfortune in the most disheartened terms. “Anyway,” I conclude, “in a few months I'll be dead.”

Â

Â

Â

During the flight the next day, I study Jim's slides. Bits of plan escape from bits of film. Hope returns. I end up covering pages of the WTC

cahier

with my beloved lists and schedules.

cahier

with my beloved lists and schedules.

Here is the best one:

PARIS: Jean-Louis/final plans and dates

GERMANY: Francis/money

PARIS: build model/find crew/how to pass the cable?

BLOIS: Omankowsky/rigging problems

VARY: rehearsing/equipment/preparations

BACK TO NEW YORK!

Upon landing, I go see Jean-Louis. With pride, I unpack my photos, the

cahier

, my information, my perfect knowledge of the towers. It doesn't produce the effect I expected. Yes, the pictures from the helicopter impress him, yes, he salutes my promenading at length inside both towers, but he still doesn't find any answers to his essential questions concerning the coup.

cahier

, my information, my perfect knowledge of the towers. It doesn't produce the effect I expected. Yes, the pictures from the helicopter impress him, yes, he salutes my promenading at length inside both towers, but he still doesn't find any answers to his essential questions concerning the coup.

Why won't Jean-Louis share my enthusiasm?

Â

The next day, I go to meet Francis, who is juggling in a circus somewhere in Germany.

Why do I decide to hitchhike, with no money and no luggage, when my foot is not yet healed and I am the owner of a truck in perfect working order? And why, after only an hour of waiting at the highway entrance, do I give up on signaling the passing cars, and begin to walk toward Germany? Have I gone insane?

Â

No. I'm thirsty for freedom, for adventure.

I walk for miles and miles on French, on German asphalt, in the rain, belting songs, barefoot when my wound wakes up. I sleep in barns. I pick up leftover bread in train station cafeterias. Far away I see the cathedral of Frankfurt. I reach the white-and-green big top of Circus Sarrasani. I lift the canvas.

Francis is rehearsing the six hoops. He asks, “Why are you here? Why didn't you call?”

With machine-gun delivery, I explain, “I-just-came-back-from-New-York-I-rented-a-helicopter-I-sneaked-into-the-towers- hundreds-of-times-I-know-them-by-heart-I-have-thousands-of -photographs-dozens-of friends-to-help-me-I'm-about-to-build-a-model-of the-two-roofs-I'm-going-rehearsing-in-the-country-I-must-buy-equipment-and-airline-tickets-to-bring-the-crew-to- New-York-we-must-rent-an-apartment-and-eat-during-the-entire-preparation ⦔

Out of breath, I conclude, “I came ⦠I need money!”

Â

Francis backs up, startled. “But, Philippe, why didn't you call? I can't give you any money today. Come back next week.”

“I'll be back!”

Â

Â

Â

Back to rue Laplace. With my pictures and sketches as references, I help Phil, the model maker, build a scale wooden replica of the two roofs and the three floors below. The baseboard is so large it occupies the whole width of the broom closet I call home, balancing

between the tiny woodworking bench and the gutted piano I use as a desk. But everything is glued, too late for changes.

between the tiny woodworking bench and the gutted piano I use as a desk. But everything is glued, too late for changes.

I resign myself to crawling under the model to get to the door or go to bed. I am reminded of Marie-Antoinette, in her cell at the Conciergerieâor was it the Bastille?âwaiting to be beheaded: every time she was called for interrogation, she had to come out through a low postern, which forced her to bow to the waiting magistrates. She solved that problem by walking out with her torso upright on acutely bent legs.

I can't do that, the model is too low. So I bow to WTC twenty times a day.

Â

Â

Â

The next decision concerns cavalettis; how many to use and how far apart to space them. The questions of where to attach them and how to keep them tight will come later.

To the model, I quickly add a high wire of red sewing thread, and to the wire, two pairs of blue-thread cavalettis. These two ropes ride the walk cable, creating four legs inclined toward the ground; their purpose is to reduce the vibrations on the wire. Because they create an area of steadiness, because they reduce the emptiness by constructing a three-dimensional shape in the void, because they offer an additional object of visual focus, and because the wirewalker feels he can hold on to them in case of trouble, the places where the cavaletti ropes connect with the cable always represent a safe haven. The wise rigger of high wires spaces his cavalettis prudently.

I try various intervals on the model but have difficulty appreciating the distances on such a small scale, so I grab a piece of chalk and, bending under the model, rush outside.

At the place du Pantheon, I draw a line on the pavement 60 meters long. I mark several different cavaletti arrangements, each time trying the wire by slowly walking its length, focusing on the anchor point far ahead and carrying an immense, invisible balancing pole â¦

“Asshole!”

“What the fuck are you doing?”

“Are you nuts?”

Three angry motorists in succession nearly run me over. In my excitement, I was not fully aware that I had drawn the wire in the middle of a curve in the road, and that darkness had already fallen upon Paris.

Â

Â

Â

What is this? A crumpled note taped to my mailbox reads, “Hi Philippe!” It's signed “Le cheval.” The mystery repeats itself three days in a row. Then there is a knock on the door. Ah, my friend Mark from Australia! Of course: “the horse.” I had forgotten how, during the night of illegal rigging on the bridge, I had jumped on his back despite his full load of equipment and screamed “Charge!” and he had dashed ahead, galloping.

I tell the shaggy, smiling young giant about my new clandestine project.

An hour later, my Australian accomplice says yes to WTC.

Â

Â

Â

I spend most of my time tying threads of different colors to the model, vainly trying to figure out where to anchor the wire, how many cavalettis are needed, and where to tie them. Annie has to drag me out to eat, force me to sleep. As my frustration grows, she keeps repeating, “Go ask Omankowsky.”

Professor Rudy Omankowsky, Sr.â“Papa Rudy,” creator and director of the illustrious Czechoslovakian troupe of wirewalkers Les Diables Blancsâhas been my mentor, rigging-wise, all along. Already several of his expensive secrets (yes, in the beginning I had to buy them!) have saved my life. There's no one better to quickly set a cable between two mountains, over a lake, or across a city, but Omankowsky knows nothing about swaying skyscrapers, doesn't believe in finely tuned rigging, and hates engineers.

Jean-Louis comes to look at the model. He examines my forest of threads.

Jean-Louis comes to look at the model. He examines my forest of threads.

“So, you figured out how to pass the cable!”

Shit, he's right! Before the cable can be anchored, or guy-lined with cavalettis, it must be passed across the void. And in order to pull across the heavy cable, first a thin light line must be set between the towers, followed by thicker and stronger ropes, and ultimately the cable.

How to get a fishing line across? In the dark. Quickly. Without noise. Without being seen. Without failure.

We start to brainstorm.

What about hitting a tennis ball with a racket or a golf ball with a club, or kicking a soccer ball? Sure, but with some leeway on both the transmitter's and the receiver's sides, to land the object not on the edge of the building but in the middle of the roof, the distance becomes almost 100 meters, 300 feetâtoo great to be that sure, that accurate. Plus there's the drag of the line â¦

“What about a bow and arrow?” suggests Jean-Louis.

“And why not a boomerang while you're at it? Ridiculous!” I snap.

I propose a fly-fishing rod, with a lead weight instead of a hook. A trap-shooting machine flinging a clay pigeon. Even two ballast-terminated ropes, one swaying from each roof, drawn to connect in the middle by magnets!

Jean-Louis goes from the bow to the crossbow to the harpoon gun.

Why not a cannon? I ask. Why not a launching ramp complete with radio-guided rocket? Oh, that's it: an airplane! One of those miniature models operated by remote control.

We run to the bottom of rue de la Montagne Ste. Geneviève, where there is a shop specializing in such things. I am distracted by the helicopters in the window. We'll tie the fishing line to the skid, I tell Jean-Louis, guide the chopper up, straight, down, and we're done. Or, we'll do it from the ground, unnoticed, then return the next day to find the fishing line already across, waiting for us. We could also use the helicopter as a getaway vehicle for

Jean-Louis's filmâsend it to a nearby rooftop before the cops can confiscate it ⦠. But Jean-Louis is already inside the store, so I follow.

Jean-Louis's filmâsend it to a nearby rooftop before the cops can confiscate it ⦠. But Jean-Louis is already inside the store, so I follow.

This is no toy shopâit's for serious model makers. A very professional man in a white lab smock asks us questions. It is clear he first suspects us of wanting to smuggle drugs across the border. When he understands that our objective is to pass a fishing line between two buildings, he gives us a smile of pity and lectures us on the difficulties of radio-guiding model airplanes. He estimates it would take us a year or two to master the beginner's model. “Add to that a couple of years if you wish to control the helicopter.”

Add to that, I'm completely uninterested

, I say to myself, having just heard a salesman at the other end of the store demonstrating how to start an engine: these mini-motors make more racket than the buses outside. So much for stealth.

, I say to myself, having just heard a salesman at the other end of the store demonstrating how to start an engine: these mini-motors make more racket than the buses outside. So much for stealth.

Another precious hour lost.

Â

Â

Â

Did I mention

Metropolis

?

Metropolis

?

Still looking to update my technical file on WTC, with Annie posing as my secretary I wangle a meeting with an architectural publisher to pitch an article on the twin towers, complete with an interview of the workers at the top.

I'm not in the mood. My acting is at its worst. Rather than throw me out, the lady behind the desk, to get rid of me and out of compassion for the loser I am, kindly gives me some sort of letter of introductionâjust a line scribbled on a large bristol card imprinted with her company's logo.

At home, I attempt to transform this not very useful document into a better one, adding text and substituting my own phone number.

The result is less than acceptable.

Â

I'm furious. Another precious day lost.

Other books

Her Tiger Billionaire by Lizzie Lynn Lee

The Cadaver Game by Kate Ellis

Hathor Legacy: Outcast by Bailey, Deborah A

Infidelity by Stacey May Fowles

Soul Identity by Dennis Batchelder

Rocky Mountain Redemption by Pamela Nissen

When We Were Sisters by Emilie Richards

I Don't Know How the Story Ends by J.B. Cheaney

Glass by Ellen Hopkins

Chasing the Storm by Martin Molsted