Tutankhamen (19 page)

Authors: Joyce Tyldesley

Following Tutankhamen's ascent to the throne, Ankhesenamen, her head restored to normal proportions, became a vigorous and conspicuous queen in the tradition of her mother Nefertiti and her grandmother Tiy. She appears on a number of Tutankhamen's monuments, while a statue of the goddess Mut, recovered from the Luxor temple,

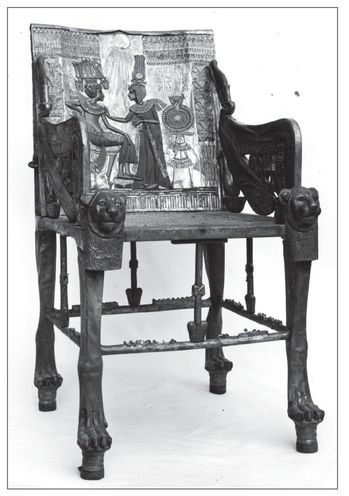

has what art-experts have identified as Ankhesenamen's face (Plate 10). Within his tomb, Ankhesenamen features on several of her husband's grave goods. On the front panel of the back of the âGolden Throne' for example, one of Tutankhamen's four thrones, we see what Carter describes as:

has what art-experts have identified as Ankhesenamen's face (Plate 10). Within his tomb, Ankhesenamen features on several of her husband's grave goods. On the front panel of the back of the âGolden Throne' for example, one of Tutankhamen's four thrones, we see what Carter describes as:

⦠one of the halls of the palace, a room decorated with flower-garlanded pillars, frieze of uraei (royal cobras), and dado of conventional ârecessed' panelling. Through a hole in the roof the sun shoots down life-giving protective rays. The king himself sits in an unconventional attitude upon a cushioned throne, his arm thrown carelessly across its back. Before him stands the girlish figure of the queen, putting, apparently, the last touches to his toilet: in one hand she holds a small jar of scent or ointment, and with the other she gently anoints his shoulder or adds a touch of perfume to his collar. A simple homely little composition, but how instinct with life and feeling it is, and with what a sense of movement!

25

25

This throne was recovered, wrapped in linen, from beneath the hippopotamus bed in the Antechamber. This may not, however, have been its original location; Carter believed that it was placed there by the 18th Dynasty restorers.

26

Standing just over a metre tall, it is a wooden chair with a solid, slightly sloping back panel, arms, openwork side panels and four legs carved to resemble lion legs. Two carved lion heads stand proud of the top of the two front legs. Originally these legs would have been connected by a carving representing the âunification of the two lands', but this was torn away by the ancient tomb robbers. The chair was covered in gold and silver foil and inlaid with colourful stones, glass and faience.

26

Standing just over a metre tall, it is a wooden chair with a solid, slightly sloping back panel, arms, openwork side panels and four legs carved to resemble lion legs. Two carved lion heads stand proud of the top of the two front legs. Originally these legs would have been connected by a carving representing the âunification of the two lands', but this was torn away by the ancient tomb robbers. The chair was covered in gold and silver foil and inlaid with colourful stones, glass and faience.

As most ancient Egyptians squatted on the floor, or sat on low stools, chairs were a luxury item, indicative not only of wealth, but also of power. They therefore made a very suitable place to display

official propaganda. This piece clearly has its artistic roots in Amarna theology, although a serious attempt has been made to adapt it to the new orthodoxy. The two side panels display winged uraei wearing the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt; on these panels, Tutankhamen's name is given as âTutankhaten'. The centre back panel shows the scene described by Carter. Ankhesenamen is standing to anoint her husband, who sits in an elaborate chair. Above the royal couple an Amarna sun disc shines, its long rays ending in small, human-style hands. Rather than a âsimple homely little composition', Ankhesenamen is here playing the role of Weret-Hekau, âgreat of magic', a goddess strongly linked to the king's coronation and crowns.

27

It is clear that this scene has been altered; the royal headdresses, for example, interrupt the sun's rays and are presumably late additions. The names of the royal couple are given in their later, Amen-based form, but they appear to have been altered from the earlier, Aten-based form. It would appear that this piece was made soon after the king's accession (or even made for a different king?) and then rather roughly adapted to suit Tutankhamen's needs.

official propaganda. This piece clearly has its artistic roots in Amarna theology, although a serious attempt has been made to adapt it to the new orthodoxy. The two side panels display winged uraei wearing the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt; on these panels, Tutankhamen's name is given as âTutankhaten'. The centre back panel shows the scene described by Carter. Ankhesenamen is standing to anoint her husband, who sits in an elaborate chair. Above the royal couple an Amarna sun disc shines, its long rays ending in small, human-style hands. Rather than a âsimple homely little composition', Ankhesenamen is here playing the role of Weret-Hekau, âgreat of magic', a goddess strongly linked to the king's coronation and crowns.

27

It is clear that this scene has been altered; the royal headdresses, for example, interrupt the sun's rays and are presumably late additions. The names of the royal couple are given in their later, Amen-based form, but they appear to have been altered from the earlier, Aten-based form. It would appear that this piece was made soon after the king's accession (or even made for a different king?) and then rather roughly adapted to suit Tutankhamen's needs.

Â

11. Tutankhamen's âGolden Throne'.

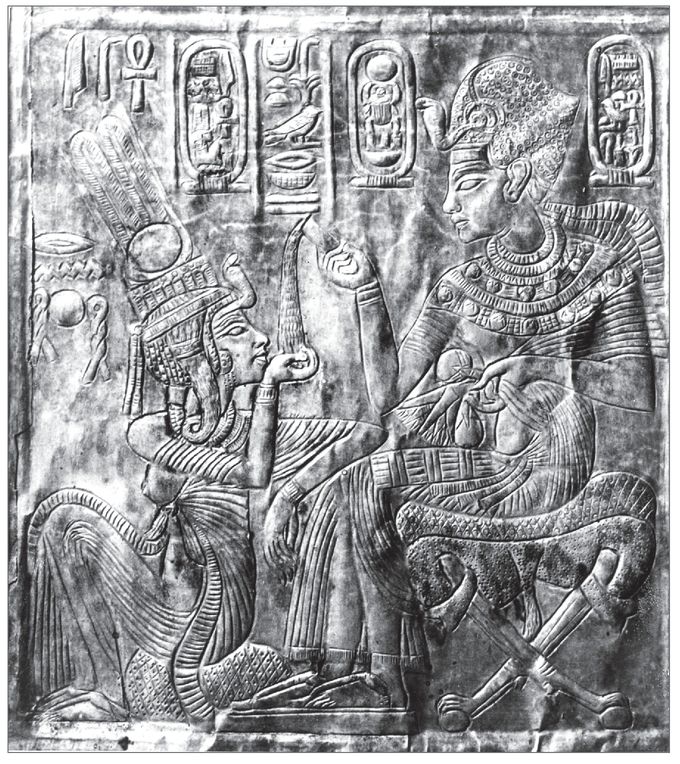

The âLittle Golden Shrine', also discovered in the Antechamber near the hippopotamus bed, was decorated with yet more pleasing domestic scenes:

⦠depicting, in delightfully naive fashion a number of episodes in the daily life of king and queen. In all these scenes the dominant note is that of friendly relationship between the husband and wife, the unselfconscious friendliness that marks the Tell el Amarna school.

28

28

Carter is again forgetting the cardinal rule that no royal art was ever commissioned for its decorative value. Art, like writing, was a means of reinforcing truth or, if necessary, a means of correcting history and creating truth. No piece of official Egyptian art can ever be taken at face value no matter how informal it may seem, and it is only in the scribbled graffiti, and the occasional incidental figures that appear in private tombs, that we can glimpse real life being lived. Looking again at the shrine, we see that it represents

Per-Wer

, the shrine of the vulture goddess Nekhbet. It is essentially a double-doored wooden box (measuring 50.5 Ã 26.5 Ã 32 cm) with a sloping roof, mounted on a sledge. Inside the shrine Carter discovered the ebony pedestal for a now vanished statuette, parts of a corselet, and a beaded necklace bearing an amulet of Weret-Hekau, who appears as a human-headed snake to suckle the miniature Tutankhamen and prepare him for his coronation. Weret-Hekau was just one of several goddesses, Hathor, Isis and Neith included, who might assume the role of king's mother and, in so doing, impart the right to rule via their milk. She personified the magic of the royal crowns and, as she might also serve as the uraeus, she might be considered an aspect of the cobra goddess Wadjet.

Per-Wer

, the shrine of the vulture goddess Nekhbet. It is essentially a double-doored wooden box (measuring 50.5 Ã 26.5 Ã 32 cm) with a sloping roof, mounted on a sledge. Inside the shrine Carter discovered the ebony pedestal for a now vanished statuette, parts of a corselet, and a beaded necklace bearing an amulet of Weret-Hekau, who appears as a human-headed snake to suckle the miniature Tutankhamen and prepare him for his coronation. Weret-Hekau was just one of several goddesses, Hathor, Isis and Neith included, who might assume the role of king's mother and, in so doing, impart the right to rule via their milk. She personified the magic of the royal crowns and, as she might also serve as the uraeus, she might be considered an aspect of the cobra goddess Wadjet.

The box had been plastered, then covered in thick gold foil.

Eighteen scenes carved into the foil show Ankhesenamen assuming a priestly role before her seated husband. She pours liquid into his ceremonial goblet and, in so doing, assumes the role of Weret-Hekau. In other scenes she mirrors the traditional postures of the goddess Maat, divine personification of truth (

maat

) and constant companion to the king, as she squats at Tutankhamen's feet to receive the water which he pours into her cupped hands, or passes him an arrow to shoot in the marshes. The apparently simple, intimate scenes should probably be read as confirmation of the queen's role in supporting her husband in his royal duties. More specifically, it seems that she is preparing him for his coronation and for his participation in the New Year ceremonies. Ankhesenamen serves as the earthly representative of Maat, or of the goddess Hathor/Sekhmet, while Tutankhamen is presented as the son of Ptah and Sekhmet, the son of Amen and Mut, and the image of Re.

29

Here on the Little Golden Shrine we have confirmation, if confirmation is needed, of the uniquely important role played by Ankhesenamen throughout Tutankhamen's reign and, perhaps, beyond it.

Eighteen scenes carved into the foil show Ankhesenamen assuming a priestly role before her seated husband. She pours liquid into his ceremonial goblet and, in so doing, assumes the role of Weret-Hekau. In other scenes she mirrors the traditional postures of the goddess Maat, divine personification of truth (

maat

) and constant companion to the king, as she squats at Tutankhamen's feet to receive the water which he pours into her cupped hands, or passes him an arrow to shoot in the marshes. The apparently simple, intimate scenes should probably be read as confirmation of the queen's role in supporting her husband in his royal duties. More specifically, it seems that she is preparing him for his coronation and for his participation in the New Year ceremonies. Ankhesenamen serves as the earthly representative of Maat, or of the goddess Hathor/Sekhmet, while Tutankhamen is presented as the son of Ptah and Sekhmet, the son of Amen and Mut, and the image of Re.

29

Here on the Little Golden Shrine we have confirmation, if confirmation is needed, of the uniquely important role played by Ankhesenamen throughout Tutankhamen's reign and, perhaps, beyond it.

Â

12. Tutankhamen and Ankhesenamen featured on the âLittle Golden Shrine'.

5

AUTOPSY

To most investigators, and especially to those absorbed in archaeological research, there are moments when their work becomes of transcending interest, and it was now our good fortune to pass through one of those rare and wonderful periods. The time that immediately followed we shall ever recall with the profoundest satisfaction. After years of toil â of excavating, conserving and recording â we were to see, with the eye of reality, that which we had hitherto beheld only in imagination.

Howard Carter

1

1

Of the many thousands of artefacts within Tutankhamen's tomb, the king's mummy should have been considered the ultimate artefact. Yet, perhaps because it fell into an uncomfortable no-man's-land between object and human remains, it received curiously little attention from the excavation team. Carter, usually so meticulous in preserving the most trivial of details, seems to have been happy to leave the recording

of the autopsy to others more suitably qualified. The anatomist Douglas Derry, the first to examine Tutankhamen's body, published a brief summary of his work as an appendix to Carter's second popular Tutankhamen book (1927) but, at Carter's request, this was written to be âcomprehensible to the layman and the man in the street.'

2

His longer and more scientific report remained unpublished and forgotten until, in 1972, dental surgeon F. Filce Leek reconstructed the results of the original autopsy and published

The Human Remains from the Tomb of Tut'ankhamūn

.

of the autopsy to others more suitably qualified. The anatomist Douglas Derry, the first to examine Tutankhamen's body, published a brief summary of his work as an appendix to Carter's second popular Tutankhamen book (1927) but, at Carter's request, this was written to be âcomprehensible to the layman and the man in the street.'

2

His longer and more scientific report remained unpublished and forgotten until, in 1972, dental surgeon F. Filce Leek reconstructed the results of the original autopsy and published

The Human Remains from the Tomb of Tut'ankhamūn

.

Â

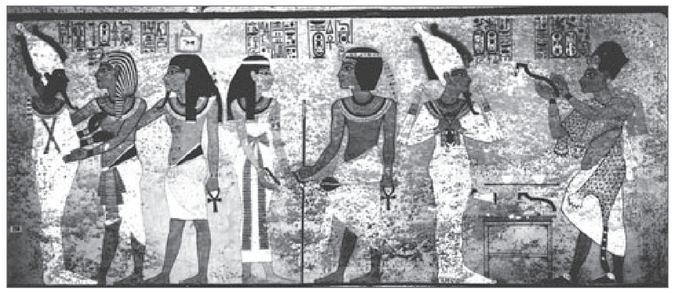

13. The north wall of his Burial Chamber shows the mummified Tutankhamen undergoing the âOpening of the Mouth ceremony' conducted by Ay (right), the human-form Tutankhamen being welcomed by the goddess Nut (middle), and Tutankhamen and his ka-spirit being embraced by the king of the dead, Osiris.

Artificial mummification was a practical response to the desire to preserve the corpse for ever. This desire for preservation was itself a response to the unique Egyptian belief that only those with a lifelike body could hope to live beyond death, as that body would provide a vital bridge between the spirit of the deceased and the offerings provided by the living. Today, even though the Egyptians are not the only

people to have attempted the artificial preservation of the corpse, mummification has become the defining ancient Egyptian ritual, and the bandaged mummy the defining Egyptian artefact.

people to have attempted the artificial preservation of the corpse, mummification has become the defining ancient Egyptian ritual, and the bandaged mummy the defining Egyptian artefact.

Mummification was both a practical science and a religious rite. To create a proper mummy â a bandaged, inert Osiris carrying the potential for life â both elements had to be present. No mummy, no matter how neat its bandages, could hope to be restored to life if it had not undergone the correct rituals in the undertaker's workshop. While the ritual aspects of the process are almost entirely lost, we have a reasonable understanding of the bloody and violent practicalities of mummification, derived from modern experimentation (which, naturally, has its limitations), the scientific investigation and occasional unwrapping of ancient mummies, and the works of the Classical authors who were happy to record all they could of what they regarded as a quite frankly bizarre practice. Herodotus' down-to-earth description has proved most useful here and, although it is unlikely that he ever paid a visit to an undertaker's workshop when he visited Egypt in the fifth century BC, his account agrees in many respects with modern observations:

The most perfect process is as follows: as much as possible of the brain is extracted through the nostrils with an iron hook, and what the hook cannot reach is rinsed out with drugs; next the flank is laid open with a flint knife and the whole contents of the abdomen removed; the cavity is then thoroughly cleansed and washed out, first with palm wine and again with an infusion of pounded spices. After that it is filled with pure bruised myrrh, cassia, and every other aromatic substance with the exception of frankincense, and sewn up again, after which the body is placed in natron, covered entirely over, for seventy days â never longer. When this period, which must not be exceeded, is over, the body is washed and wrapped from head to foot in linen cut into strips and smeared on the underside with gum,

which is commonly used by the Egyptians instead of glue. In this condition the body is given back to the family, who have a wooden case made shaped like the human figure, into which it is put.

3

which is commonly used by the Egyptians instead of glue. In this condition the body is given back to the family, who have a wooden case made shaped like the human figure, into which it is put.

3

Other books

The Devil to Pay by Liz Carlyle

The Balled And The Beautiful: A College Sports Romance Story by Chance, Nicole

My Laird's Castle by Bess McBride

The Catch by Richard Reece

TRAPPED by Beverly Long - The Men from Crow Hollow 03 - TRAPPED

A Treasure Worth Seeking by Sandra Brown

Hot Little Hands by Abigail Ulman

Deadline by Sandra Brown

Desert of the Damned by Kathy Kulig

Die For You by A. Sangrey Black