Tutankhamen (23 page)

Authors: Joyce Tyldesley

The resin-hardened linen packing the chest cavity had prevented Derry from conducting a full examination of the upper torso. Harrison's X-rays therefore came as something of a shock: there was obvious and extensive damage in this region, and the sternum and part of the ribcage were missing. Clearly, Tutankhamen could not have been born without his breastbone. This damage must have occurred at or immediately prior to mummification, or, perhaps, during Derry's examination. Derry, however, makes no mention of removing the chest â it is difficult to understand why he would wish to do so â and it seems as if some at least of the ribs were broken in antiquity rather than cut during the autopsy. Harrison also noted that Tutankhamen's heart was absent: a curious omission given that the heart had important duties to perform in the afterlife. A black resin scarab, inscribed with

Book of the Dead

spell 29b, may have been intended as its replacement.

Book of the Dead

spell 29b, may have been intended as its replacement.

The heart was not the only body-part missing. Tutankhamen's penis was clearly visible in Burton's photographs, yet Harrison could not find it. For a long time the rumour circulated that it had been stolen as a ghoulish souvenir, probably during the Second World War when the tomb was not well guarded. This led to accusations of gross negligence â and a host of unfortunate puns regarding the lost âcrown jewels' â which only subsided when in 2006 the Hawass team discovered the penis hidden in the loose sand of the tray. Dr Eduard Egarter Vigl, an expert in mummified members, has since been able to confirm that although the penis had shrunk during the mummification

process, and had been somewhat flattened by its bandages, the young king was ânormally built'.

36

Recent Examinationprocess, and had been somewhat flattened by its bandages, the young king was ânormally built'.

36

Hawass's team confirmed that Tutankhamen's chest had suffered serious damage prior to mummification (or, less likely, during Derry's autopsy) and that his pelvic bones were almost entirely missing. They also noted that his left thigh had been broken at, or very close to, the time of death. Their work indicated that Tutankhamen may have suffered a whole host of health problems, including a left club-foot, diseased bones in his right foot, a cleft palate, scoliosis and malaria. Many of these conclusions have been challenged; in particular, the diagnosis of the congenital abnormality club-foot (

Talipes equinovarus

) is open to question, as it is not unknown for âclub-foot' to be the result of warping caused by over-tight bandages.

37

Was Tutankhamen a sickly king with mobility problems? His tomb included 130 walking sticks and canes, but the stick could also be a symbol of authority, a weapon and a piece of sporting equipment. Alongside the sticks there were armour, six chariots and an arsenal of bows and arrows, throwing sticks, slings, clubs, swords, shields and daggers. Images and artefacts from his tomb show Tutankhamen sitting to perform tasks â shooting, for example â where we might reasonably have expected him to stand, but they also show him standing to perform heroic deeds: the brave (or foolhardy?) Tutankhamen balances on a fragile papyrus boat to harpoon a hippopotamus in the marshes, or drives his chariot at speed as he chases ostriches across the desert. On his Painted Box he again stands triumphant in his chariot as he defeats his Syrian enemies. These images are conventional images of kingship. They conform to the centuries-old tradition which dictated that kings, whatever their actual appearance and character, should always appear physically perfect and brave. We have no understanding of the king behind this propaganda: we cannot state whether Tutankhamen was either brave or physically whole. Nor can we be certain that he ever tested himself on the battlefield. New kings traditionally reinforced their claim to the throne by provoking a fight with Egypt's traditional enemies, the Nubians to the south, and the Asiatics to the north-east. Fragmented references from the Karnak, Luxor and Medamud temples suggest that Tutankhamen's troops did campaign against both enemies, while images from the Memphite tomb of General Horemheb show Asiatics and Libyans suing for peace. However, the simple fact that the early 19th Dynasty Ramesside kings would be forced to spend many years restoring Egypt's northern border suggests that whatever their propaganda would have us believe, and whatever campaigns they actually undertook, Tutankhamen and his successors, Ay and Horemheb, were not great generals who enjoyed multiple victories.

Talipes equinovarus

) is open to question, as it is not unknown for âclub-foot' to be the result of warping caused by over-tight bandages.

37

Was Tutankhamen a sickly king with mobility problems? His tomb included 130 walking sticks and canes, but the stick could also be a symbol of authority, a weapon and a piece of sporting equipment. Alongside the sticks there were armour, six chariots and an arsenal of bows and arrows, throwing sticks, slings, clubs, swords, shields and daggers. Images and artefacts from his tomb show Tutankhamen sitting to perform tasks â shooting, for example â where we might reasonably have expected him to stand, but they also show him standing to perform heroic deeds: the brave (or foolhardy?) Tutankhamen balances on a fragile papyrus boat to harpoon a hippopotamus in the marshes, or drives his chariot at speed as he chases ostriches across the desert. On his Painted Box he again stands triumphant in his chariot as he defeats his Syrian enemies. These images are conventional images of kingship. They conform to the centuries-old tradition which dictated that kings, whatever their actual appearance and character, should always appear physically perfect and brave. We have no understanding of the king behind this propaganda: we cannot state whether Tutankhamen was either brave or physically whole. Nor can we be certain that he ever tested himself on the battlefield. New kings traditionally reinforced their claim to the throne by provoking a fight with Egypt's traditional enemies, the Nubians to the south, and the Asiatics to the north-east. Fragmented references from the Karnak, Luxor and Medamud temples suggest that Tutankhamen's troops did campaign against both enemies, while images from the Memphite tomb of General Horemheb show Asiatics and Libyans suing for peace. However, the simple fact that the early 19th Dynasty Ramesside kings would be forced to spend many years restoring Egypt's northern border suggests that whatever their propaganda would have us believe, and whatever campaigns they actually undertook, Tutankhamen and his successors, Ay and Horemheb, were not great generals who enjoyed multiple victories.

Â

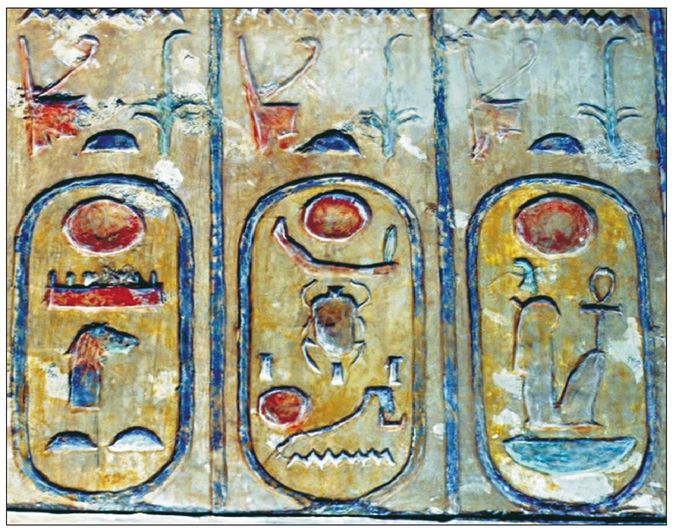

1. The Ramesside monarchs of the 19th Dynasty compiled lists of Egypt's kings, omitting any who did not conform to conventional notions of kingship. This extract from the king list taken from the Abydos cenotaph temple of Ramesses II is designed to be read from right to left. It shows the name of Amenhotep III, omits the Amarna pharaohs Akhenaten, Smenkhkare, Tutankhamen and Ay, and continues with the names of Horemheb and the first king of the 19th Dynasty, Ramesses I.

Â

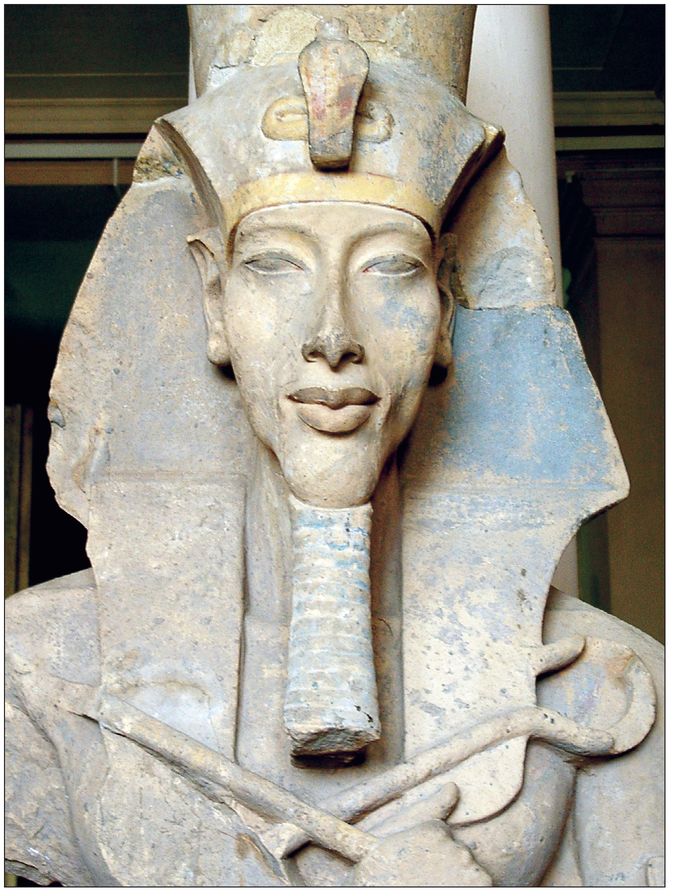

2. Head of a colossal statue of Akhenaten, recovered from the Karnak temple. Akhenaten's earliest attempts to change the focus of state religion, and the monumental presentation of kingship, occurred at Thebes. He then abandoned the traditional New Kingdom religious capital to establish a new city dedicated to the solar god known as the Aten, at the new city of Amarna.

Â

3. In this extreme example of the Amarna art style, Akhenaten exhibits a curious range of features which would have been emphasised by his tall crown: an elongated face, thick lips, almond shaped eyes and a long neck. Although some Egyptologists have interpreted Akhena ten's new, androgynous appearance as evidence of disease, most believe that it represents a new art-style which, in some way, reflects the theology of Aten worship.

Â

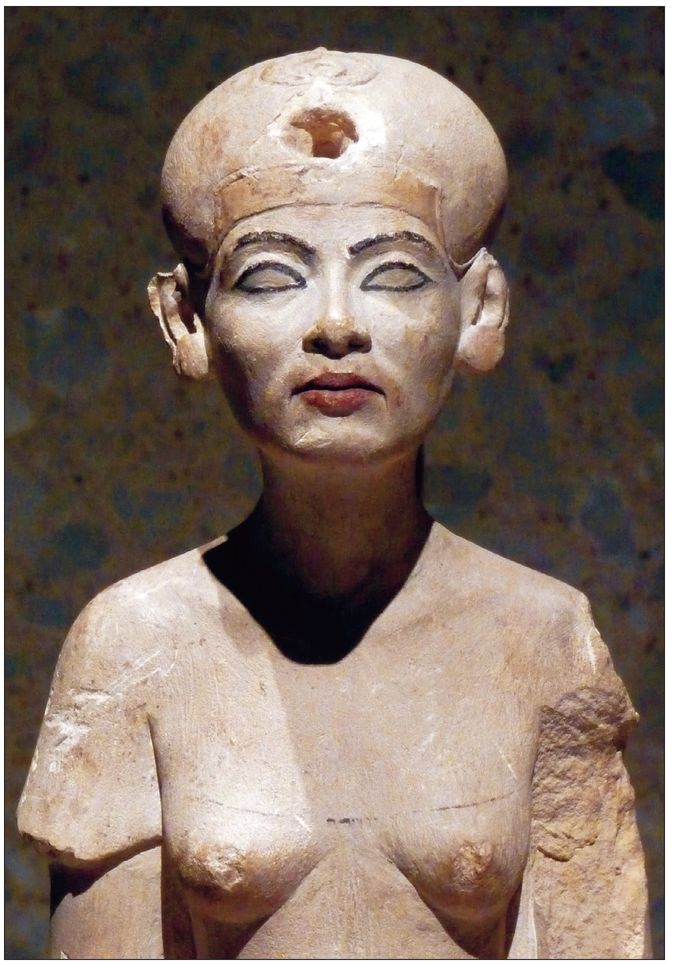

4. Nefertiti, consort of Akhenaten, depicted as a mature woman. Egyptian queens are seldom shown as older women, but both Nefertiti and her mother-in-law, the politically powerful Queen Tiy, were depicted this way.

Â

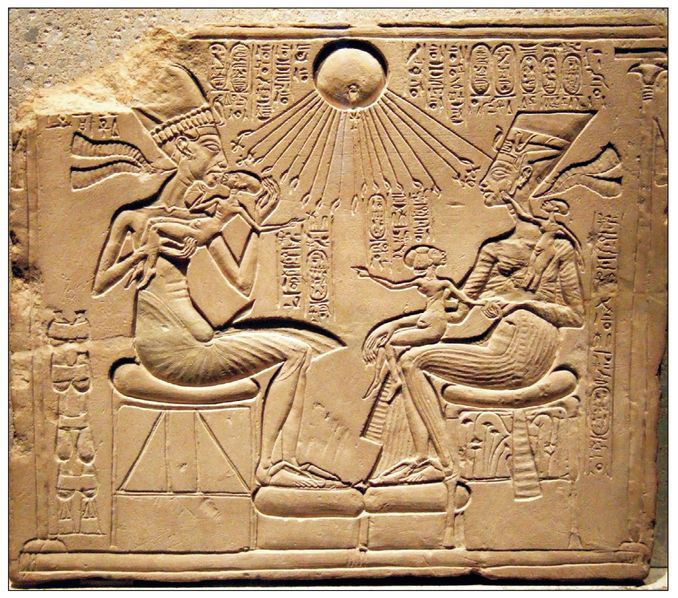

5. The Amarna royal family: Akhenaten, Nefertiti, Meritaten (with Akhenaten), Meketaten and Ankhesenpaaten (with Nefertiti). Although to modern eyes this appears to be a charming, informal scene, it is actually a carefully composed presentation of the quasi-divine royal family beneath the life-giving rays of the Aten.

Â

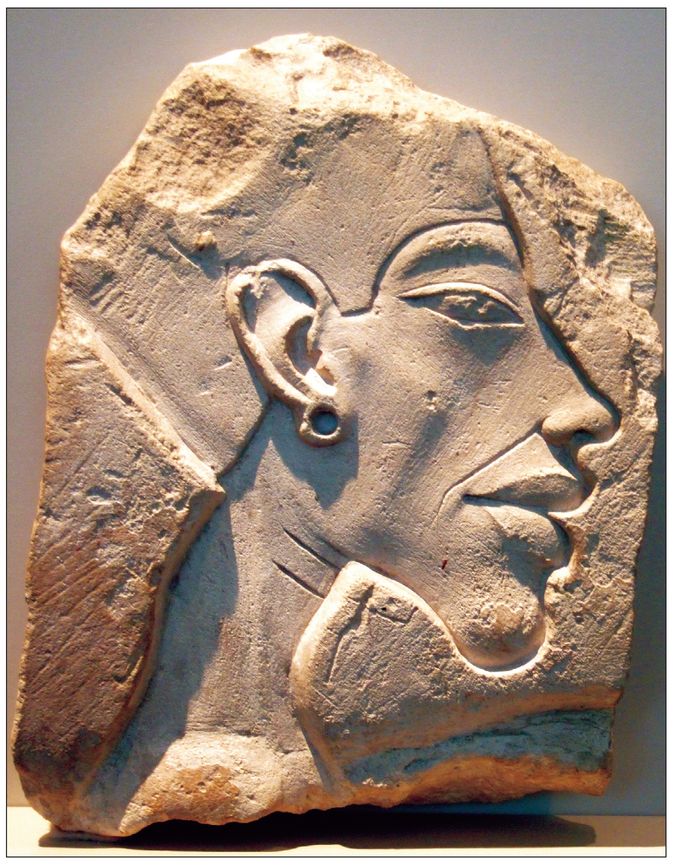

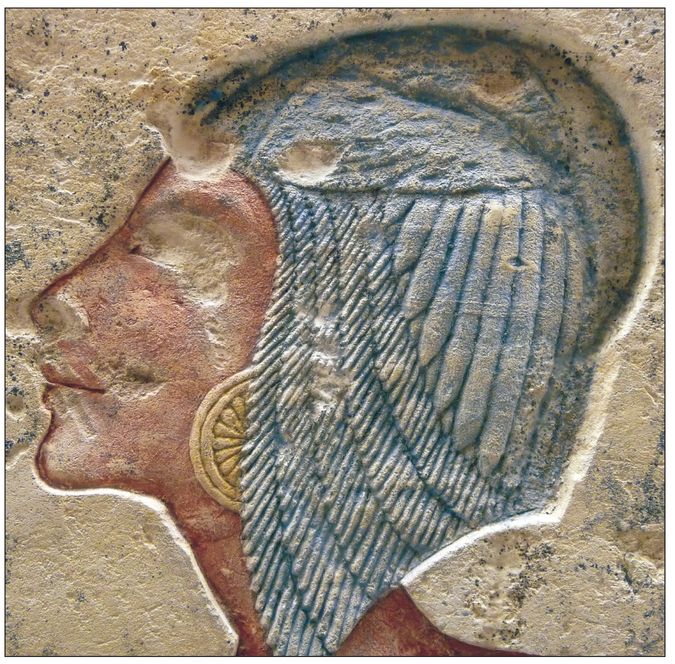

6. Limestone relief head of Kiya, secondary wife of Akhenaten, recovered from Hermopolis Magna (modern Ashmunein). Kiya originally wore a âNubian-style' wig and characteristically large earrings. However her image has been re-carved, with alterations to the head and hairstyle, so that she becomes the eldest Amarna Princess, Meritaten.

Â

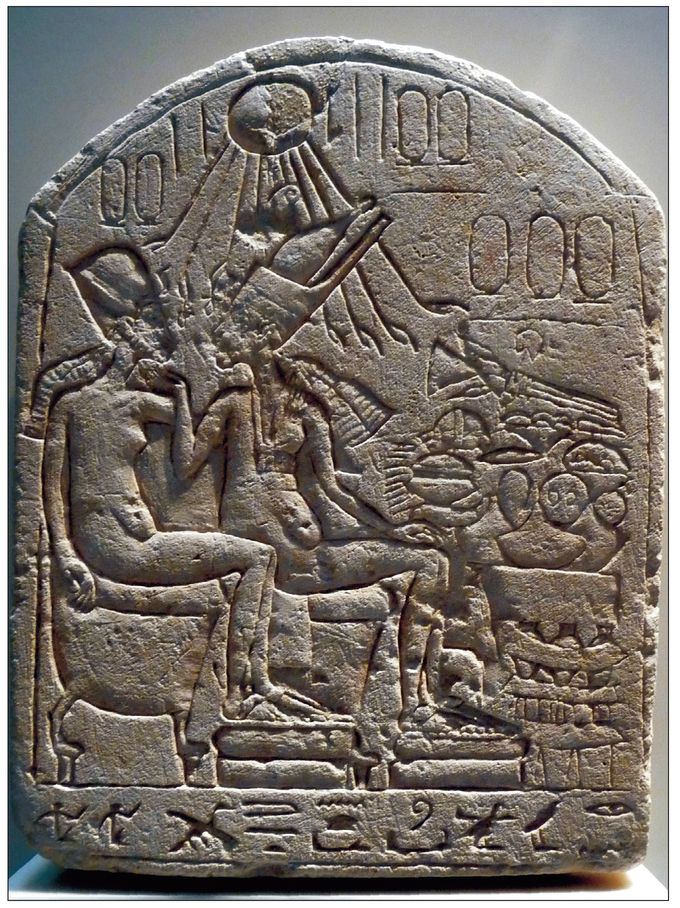

7. A damaged votive stela of unknown provenance, dedicated by the soldier Pasi. The two unnamed Amarna kings have been variously identified as Akhenaten and his consort Nefertiti, Akhenaten and his son or lover Smenkhkare, and Akhenaten and his father Amenhotep III. The cartouches that would have named the couple are empty.

Â

8. An Amarna king and an Amarna queen: again both are unnamed, but they are usually identified as Smenkhkare and Meritaten. Is the king carrying the staff which denotes his royal authority, or is he lame and using a walking stick?

Other books

An Unexpected Win by Jenna Byrnes

Tahoe Blues by Lane, Aubree

When the Lights Come on Again by Maggie Craig

Shark Trouble by Peter Benchley

Internal Medicine: A Doctor's Stories by Terrence Holt

Secret of the Stars by Andre Norton

1 Hairspray and Homicide by Cindy Bell

The Bride Price by Tracey Jane Jackson

The Total Package by Stephanie Evanovich

Mischief in Miami by Nicole Williams