Tutankhamen (26 page)

Authors: Joyce Tyldesley

Who is this âbodily father'? Given that Tutankhamen can have been no more than eight years old when the scene was carved, there are just three possibilities: Amenhotep III, Akhenaten and Smenkhkare. Under normal circumstances we would expect a king to be the son of the previous king. However, in this case we are not actually sure who the previous king was â did Smenkhkare enjoy a brief independent reign of up to two years, or did he die Akhenaten's co-regent, his own reign entirely lost within Akhenaten's own? Without Smenkhkare's body, we are unable to tell if he lived long enough to leave an eight-year-old son to succeed to the throne. However, if we assume that Smenkhkare was in the direct line of succession â a child of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, or Akhenaten and another wife, born two years before the oldest daughter, Meritaten â he would have been approximately fourteen years old when Tutankhamen was born. If Smenkhkare was a child born to Amenhotep III and Tiy (or Amenhotep III and a different queen), he could have been much older at Tutankhamen's birth.

Tutankhamen appears to settle the matter himself. The âPrudhoe Lions' are a pair of 18th Dynasty red granite statues whose multiple inscriptions reflect their complicated history. Created to guard the temple of Amenhotep III at Soleb in Nubia, they were, in the third

century BC, transferred to the Nubian city of Gebel Barkel by the Nubian king Amanislo. Finally they were transferred to the British Museum. A text carved on Tutankhamen's behalf (which was later usurped by Amanislo) announces, in no uncertain terms, that Amenhotep III is his father:

century BC, transferred to the Nubian city of Gebel Barkel by the Nubian king Amanislo. Finally they were transferred to the British Museum. A text carved on Tutankhamen's behalf (which was later usurped by Amanislo) announces, in no uncertain terms, that Amenhotep III is his father:

He who renewed the monument for his father, the King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Lord of the Two Lands, Nebmaatre, image of Re, Son of Re, Amenhotep Ruler of Thebes.

6

6

This is reinforced by his dedication, recorded on the handle of a wooden astronomical instrument, housed in the Oriental Institute Museum, Chicago, to the âfather of his father', Tuthmosis IV.

Unfortunately, we cannot accept these statements at face value. âFather', in the Egyptian language, might also be used to describe a grandfather, great-grandfather or more generalised ancestor, while âson' might also mean son-in-law, or grandson. The fact that Akhenaten reigned for seventeen years (his reign length confirmed by two jar labels) suggests that Amenhotep III died seventeen years before Akhenaten. He could only have left an eight-year-old son to rule after Akhenaten if he himself had first shared a nine-year co-regency with Akhenaten, with each king using his own year dates so that Akhenaten's Year 1 was Amenhotep's Year 29. If we are to insert a brief reign for Smenkhkare, or for the enigmatic Neferneferuaten, or for both, between the reigns of Akhenaten and Tutankhamen, the co-regency would have to have been even longer. While not entirely impossible, it seems highly unlikely that such a lengthy co-regency would pass unmentioned in the historical record.

7

7

It seems most likely that Tutankhamen was the son either of Akhenaten or of Smenkhkare. There is no sign of a royal son at the Amarna court, but this does not mean that there was no son: in this case, absence of evidence can definitely not be taken as evidence of

absence. The many images of the Amarna royal family cannot be read as the ancient equivalent of family portraits; even less can they be interpreted as casual snapshots of royal family life. While royal daughters would always remain a part of their birth family, and would be depicted offering their continuing feminine support to their father, sons were potential kings; heirs, and to a certain extent rivals, to their father. They were excluded from family groups which should best be interpreted as illustrating the king and his most devoted supporters; a combination of his mother, his consort and his daughters. This is well illustrated by Akhenaten's own birth family. We know that his mother, Tiy, bore at least six children: two sons (Tuthmosis and Amenhotep) and four daughters (Sitamen, Henut-Taneb, Isis and Nebetah). However, the two princes are completely overshadowed by their sisters, who appear regularly alongside their parents in formal art. This gives the curious effect of Akhenaten stepping forward from nowhere to take his father's throne, and has led to ingenious but misguided theories as to why he has a âhidden' childhood.

absence. The many images of the Amarna royal family cannot be read as the ancient equivalent of family portraits; even less can they be interpreted as casual snapshots of royal family life. While royal daughters would always remain a part of their birth family, and would be depicted offering their continuing feminine support to their father, sons were potential kings; heirs, and to a certain extent rivals, to their father. They were excluded from family groups which should best be interpreted as illustrating the king and his most devoted supporters; a combination of his mother, his consort and his daughters. This is well illustrated by Akhenaten's own birth family. We know that his mother, Tiy, bore at least six children: two sons (Tuthmosis and Amenhotep) and four daughters (Sitamen, Henut-Taneb, Isis and Nebetah). However, the two princes are completely overshadowed by their sisters, who appear regularly alongside their parents in formal art. This gives the curious effect of Akhenaten stepping forward from nowhere to take his father's throne, and has led to ingenious but misguided theories as to why he has a âhidden' childhood.

A potential flaw in the Akhenaten-as-father theory is the often-stated assumption that Akhenaten was incapable of fathering children because he carried a genetic abnormality. This assumption flies in the face of evidence that Akhenaten considered himself the father of Nefertiti's six daughters plus other children in the royal harem, and it begs the question of Smenkhkare's parentage. Here, of course, we are having to assume that Nefertiti, and the other ladies of the harem, were not serially unfaithful to Akhenaten.

The infertility theory is based, not on medical evidence, but on Akhenaten's artwork. For over a thousand years the rules of artistic representation had decreed that elite Egyptians should appear physically perfect, with no flaws or blemishes. Men should be either eternal youths with firm bodies and tanned skins, or mature statesmen with pendulous breasts and soft rolls of fat. Women should be beautiful, slender, pale and young (and presumably fertile), although very occasionally an

older woman might be presented as a wise elder. Initially Akhenaten adhered to this tradition, and his early portraits show a conventional if slightly plump 18th Dynasty monarch. By the end of Year 5, however, he appeared strikingly different to all previous pharaohs. His narrow head had become elongated, its length emphasised by his preference for tall headdresses and the traditional false beard. His face featured almond-shaped eyes, fleshy earlobes, a pendulous jaw, long nose, hollow cheeks, pronounced cheekbones and thick lips. His shoulders, chest, arms and lower legs were weedy and underdeveloped and his collar bone excessively prominent, yet he had wide hips, heavy thighs, rounded breasts, a narrow waist and a rounded stomach. Many early Egyptologists sought to interpret this highly feminised image as a true representation of the king himself. This led to the assumption that Akhenaten must have suffered from a serious medical condition: among the many suggestions that have been put forward are Marfan's disease, Fröhlich's syndrome, Wilson-Turner X-linked mental retardation syndrome and Klinefelter syndrome.

8

Some, but not all, of these diseases would have made Akhenaten infertile.

older woman might be presented as a wise elder. Initially Akhenaten adhered to this tradition, and his early portraits show a conventional if slightly plump 18th Dynasty monarch. By the end of Year 5, however, he appeared strikingly different to all previous pharaohs. His narrow head had become elongated, its length emphasised by his preference for tall headdresses and the traditional false beard. His face featured almond-shaped eyes, fleshy earlobes, a pendulous jaw, long nose, hollow cheeks, pronounced cheekbones and thick lips. His shoulders, chest, arms and lower legs were weedy and underdeveloped and his collar bone excessively prominent, yet he had wide hips, heavy thighs, rounded breasts, a narrow waist and a rounded stomach. Many early Egyptologists sought to interpret this highly feminised image as a true representation of the king himself. This led to the assumption that Akhenaten must have suffered from a serious medical condition: among the many suggestions that have been put forward are Marfan's disease, Fröhlich's syndrome, Wilson-Turner X-linked mental retardation syndrome and Klinefelter syndrome.

8

Some, but not all, of these diseases would have made Akhenaten infertile.

Diagnosing illness via art is a process fraught with danger: we have already seen how the young Ankhesenamen's misshapen head, once cited as evidence for the practice of infant head binding, was âcorrected' in her husband's artwork. Today, while the theory of the sick Akhenaten remains popular in alternative histories, most Egyptologists agree that Akhenaten's art cannot be read too literally; that his artists set out to depict the essence of their king, rather than his outward appearance. Furthermore, his ânew' art is not a sudden development. Akhenaten was merely speeding up and exaggerating an ongoing artistic evolution that had started during his father's reign. His new image may be loosely based on his own appearance â indeed, Tutankhamen's garments suggest a family tendency to carry weight on the hips â but this is likely to have been exaggerated to reflect his interest in a genderless, self-creating deity.

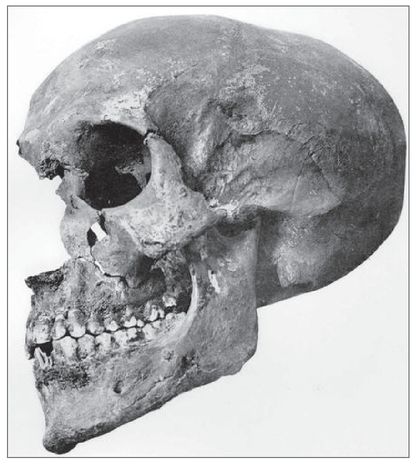

Tutankhamen's Father/Brother: KV 55 RevisitedThe damp and decomposing mummy which Davis discovered in KV 55, and which he quickly reduced to a skeleton, is today housed in Cairo Museum. Despite Davis's conviction that these were the remains of Queen Tiy, it is universally agreed that the remains are male, and that they are the remains of someone closely related to Tutankhamen. That is, however, almost all that is agreed. The experts cannot even agree on the condition of the bones, with some classifying them as very bad, others as good; meanwhile the skull shape has been described as both wide and flat, and long. So striking are these discrepancies that it is tempting to speculate that the experts may not always have examined the same body.

9

9

Tomb KV 55 yielded artefacts originating from the Amarna royal tomb. It was originally sealed with Tutankhamen's seal: this suggests that Tutankhamen was responsible for emptying the Amarna tomb and transferring its contents to Thebes. As Tutankhamen was responsible for the abandonment of Amarna, this makes sense. But Tutankhamen himself died at approximately eighteen years of age; he could not have buried an adult son. The KV 55 mummy is therefore likely to be his father (Akhenaten or Smenkhkare or some other royal individual) or his brother (Smenkhkare, an unknown royal individual or, as a very remote possibility, Akhenaten). Clearly, age at death is the crucial factor here. The older the remains, the more likely they are to be Akhenaten; the younger they are, the more likely they are to be Smenkhkare. Unfortunately, this is a matter of continuing expert debate. Smith initially estimated an age at death of twenty-five or twenty-six years. He was quite adamant about this:

⦠the estimated age of twen ty-five or twenty-six years might, in any given individual, be lessened or increased by two or three years, if his growth was precocious or delayed, respectively. The question has been

put to me by archaeologists: âIs it possible that these bones can be those of a man of twenty-eight or thirty years of age?' ⦠No anatomist would be justified in denying that this individual may have been twenty-eight, but it is highly improbable that he could have attained thirty years if he had been normal.

10

put to me by archaeologists: âIs it possible that these bones can be those of a man of twenty-eight or thirty years of age?' ⦠No anatomist would be justified in denying that this individual may have been twenty-eight, but it is highly improbable that he could have attained thirty years if he had been normal.

10

Â

18. The skull of the KV 55 mummy: Akhenaten to some, Smenkhkare to others.

Â

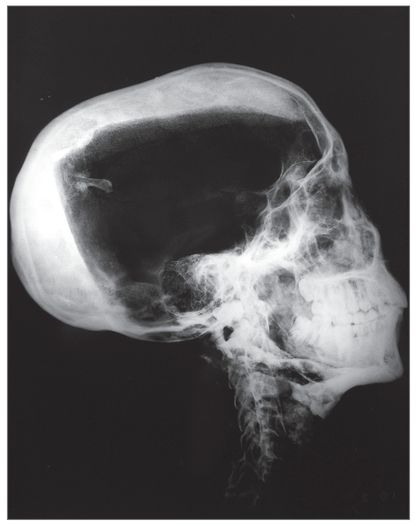

19. The Harrison X-ray of Tutankhamen's skull: the two layers of resin within the skull are clearly visible.

Smith was, however, influenced in his unswerving belief that the bones were the remains of Akhenaten. Admittedly Akhenaten was generally supposed to have lived for at least thirty years, and probably far longer, but, if he came to the throne as a child of nine or ten, and/ or if he had a long co-regency, it was not impossible that he was fairly young when he died. This does, however, raise questions about the birth of Meritaten, who was born before the end of his regnal Year 1. Smith then reconsidered his conclusion:

I do not suppose that any unprejudiced scholar who studies the archaeological evidence alone would harbour any doubt of the identity of this mummy, if it were not for the fact that it is difficult from the anatomical evidence to assign an age to this skeleton sufficiently great to satisfy the demands of most historians, who want at least 30 years into which to crowd the events of Khouniatonou's [Akhenaten's] eventful reign ⦠If, with such clear archaeological evidence to indicate that these are the remains of Khouniatonou, the historian can produce irrefutable facts showing that the heretic king must have been 27, or even 30, years of age, I would be prepared to admit that the weight of the anatomical evidence in opposition to the admission of that fact is too slight to be considered absolutely prohibitive.

11

11

Derry restored the broken skull and made a full anatomical examination of the remains, deducing that the pattern of fused and unfused epiphyses, poorly developed interdigitated cranial sagittal sutures and an unerupted right upper third molar indicated that their owner could

have been no more than twenty-five years old at death.

12

Harrison concurred: KV 55 had died at less than twenty-five years of age and, indeed, âif certain variable anatomical criteria ⦠are to be utilized, it is possible to be more definite that the age at death occurred in the 20th year'.

13

Anatomist Joyce Filer also agrees: â[the skeletal evidence] points to somebody perhaps no more than mid-twenties; certainly, by the teeth, I would go even younger than that.'

14

have been no more than twenty-five years old at death.

12

Harrison concurred: KV 55 had died at less than twenty-five years of age and, indeed, âif certain variable anatomical criteria ⦠are to be utilized, it is possible to be more definite that the age at death occurred in the 20th year'.

13

Anatomist Joyce Filer also agrees: â[the skeletal evidence] points to somebody perhaps no more than mid-twenties; certainly, by the teeth, I would go even younger than that.'

14

In stark contrast, Wente and Harris, basing their analysis primarily on the head and teeth, agree with Smith, suggesting an age of between thirty and thirty-five.

15

The most recent analysis, by the Supreme Council of Antiquities team, goes even higher, with an estimated age at death ranging from between thirty-five and forty-five years to a more improbable sixty.

16

As many commentators have spotted, if Akhenaten died aged sixty, he would actually have been several years older than his own mother Tiy (as identified by the same team as KV 35EL), who died, apparently in her forties, no more than ten years before his own death. Citing DNA evidence, the Egyptian team have identified KV 55 as both the father of Tutankhamen and a son of Amenhotep III and Tiy: this would indicate that he is either Akhenaten, Akhenaten's elder brother Tuthmosis, or an otherwise unknown brother, who could, of course, be Smenkhkare. Their conclusion is that he is âmost probably Akhenaten'. This identification, which appears to contradict the evidence offered by the bones, has provoked widespread debate, and many would still identify KV 55 as the relatively young Smenkhkare. The link with the mummy known as Amenhotep III is a curious one, as it seems highly likely that this mummy has been mislabelled, as we have already seen.

15

The most recent analysis, by the Supreme Council of Antiquities team, goes even higher, with an estimated age at death ranging from between thirty-five and forty-five years to a more improbable sixty.

16

As many commentators have spotted, if Akhenaten died aged sixty, he would actually have been several years older than his own mother Tiy (as identified by the same team as KV 35EL), who died, apparently in her forties, no more than ten years before his own death. Citing DNA evidence, the Egyptian team have identified KV 55 as both the father of Tutankhamen and a son of Amenhotep III and Tiy: this would indicate that he is either Akhenaten, Akhenaten's elder brother Tuthmosis, or an otherwise unknown brother, who could, of course, be Smenkhkare. Their conclusion is that he is âmost probably Akhenaten'. This identification, which appears to contradict the evidence offered by the bones, has provoked widespread debate, and many would still identify KV 55 as the relatively young Smenkhkare. The link with the mummy known as Amenhotep III is a curious one, as it seems highly likely that this mummy has been mislabelled, as we have already seen.

Other books

Three-Ring Terror by Franklin W. Dixon

If Truth Be Told: A Monk's Memoir by Om Swami

Euphoria-Z by Luke Ahearn

Death at Daisy's Folly by Robin Paige

America The Dead Book Two: The Road To Somewhere by Lindsey Rivers

Elemental Love by L.M. Somerton

B005GEZ23A EBOK by Gombrowicz, Witold

First Into Action by Duncan Falconer

The Cowboy Wins a Bride (The Cowboys of Chance Creek) by Seton, Cora

Sex Machine: A Standalone Contemporary Romance by Force,Marie