Tutankhamen (24 page)

Authors: Joyce Tyldesley

Â

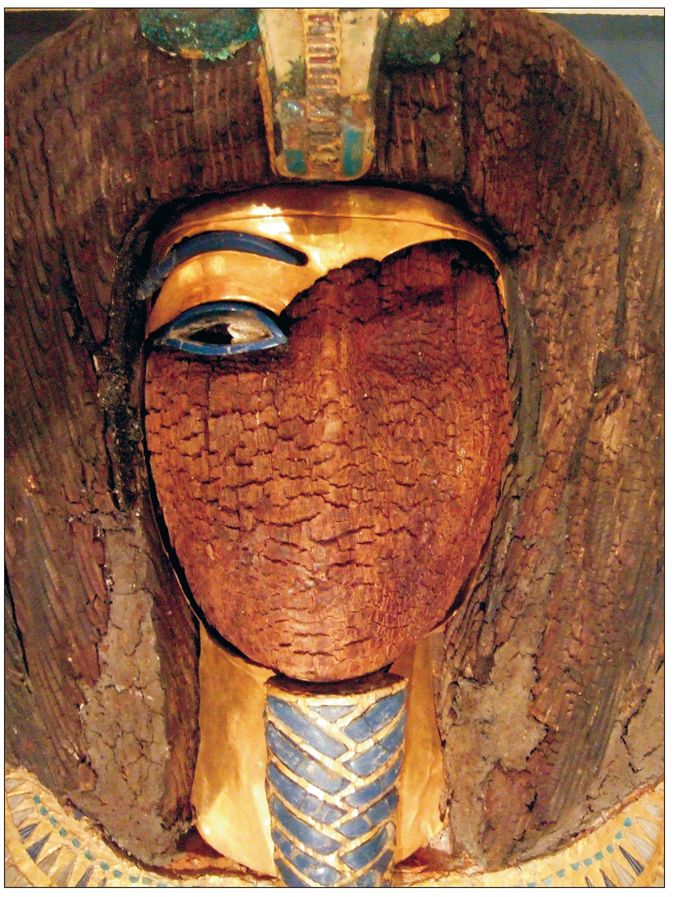

9. The badly damaged head of the anthropoid coffin recovered from tomb KV 55. The face has been ripped away but the beard and the uraeus (rearing snake on the brow) are still in place. This evidence strongly suggests that the anonymous coffin was used for a royal burial.

Â

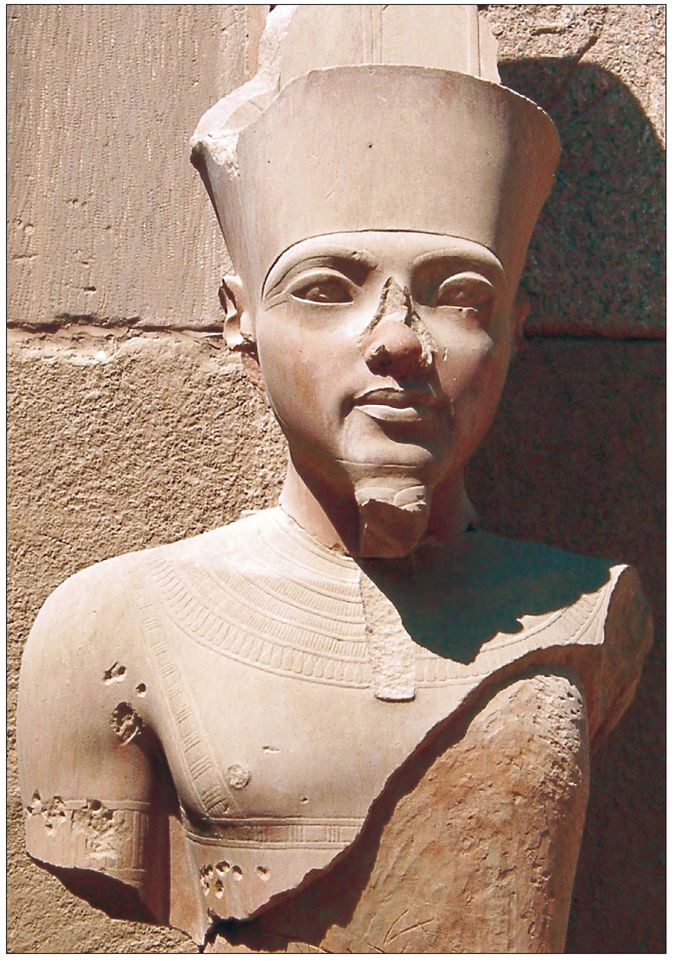

10. This statue of the god Amen, in the Karnak temple, has the features of Tutankhamen. It is a visually striking example of the way in which Tutankhamen re-associated kingship with the traditional Amen-based religion at Thebes.

Â

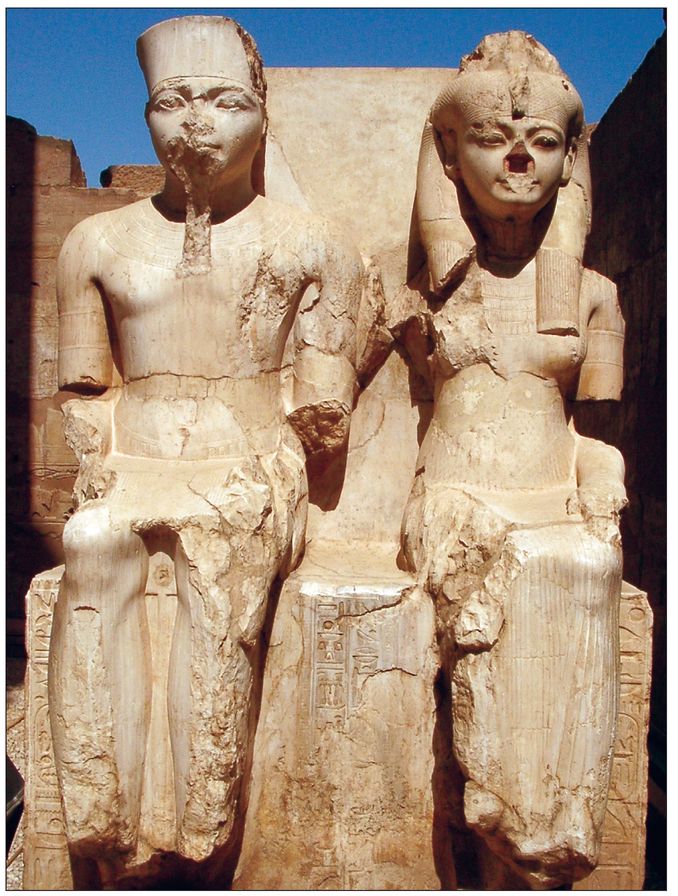

11. The god Amen and his consort Mut, in the Luxor temple. The pair have been given the distinctive facial features of Tutankhamen and his consort Ankhesenamen: the link between kingship and traditional theology is therefore obvious to all who see them. Although the Ramesside kings did not approve of Tutankhamen (see Plate 1), this image must have been considered acceptable, as it was re-inscribed by Ramesses II.

Â

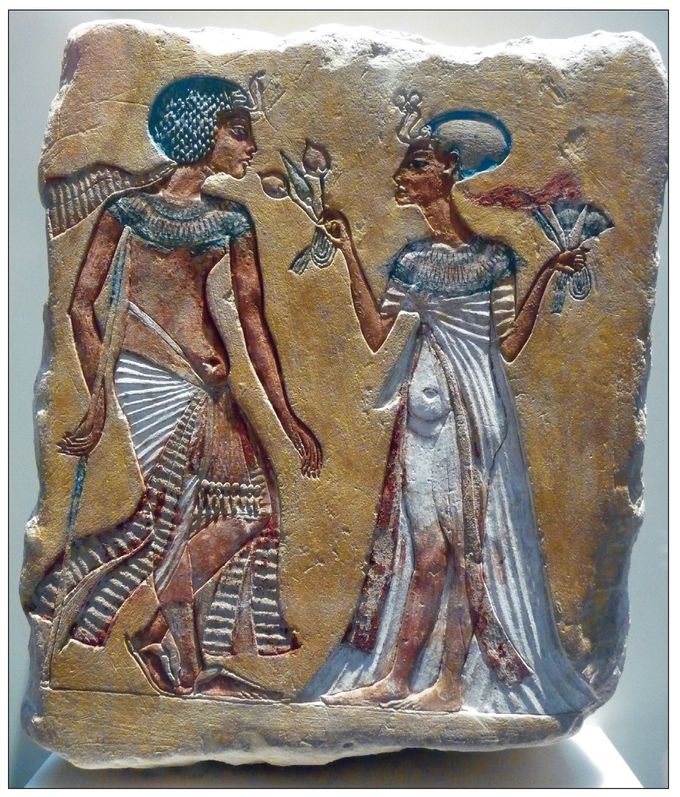

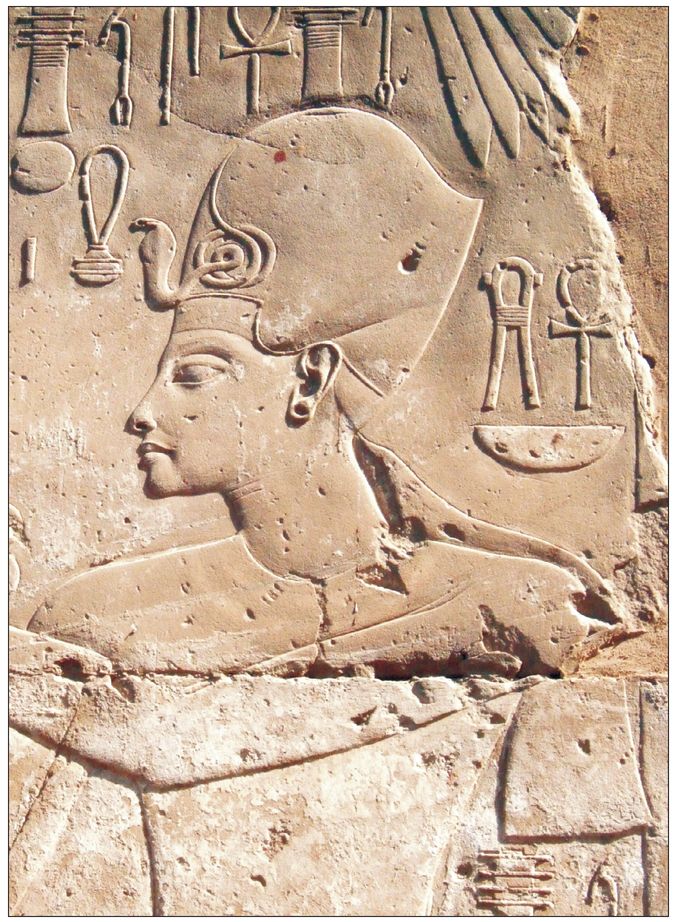

12. Reflections of the Amarna art style can be seen in the building work undertaken by late 18th Dynasty kings at Thebes. This image of Tutankhamen was later usurped by Horemheb. The king's blue war crown has obviously been re-carved and is not necessarily the crown that Tutankhamen originally wore: this crown would be very appropriate for Horemheb and his militaristic Ramesside successors.

Â

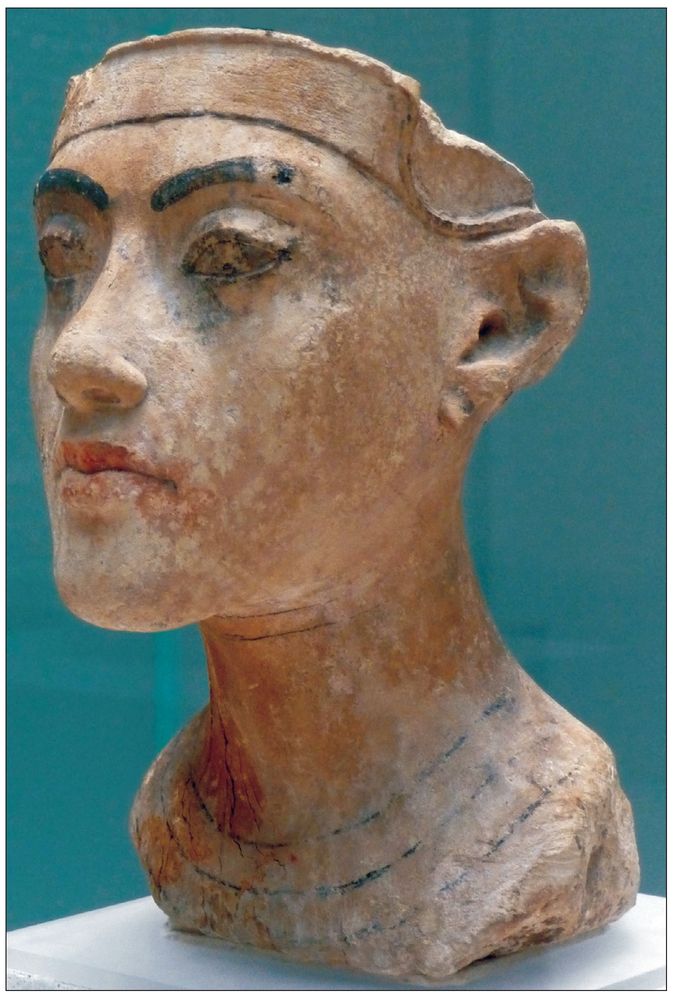

13. Unlabelled limestone head, recovered from Amarna, and believed by many to represent Tutankhamen.

Â

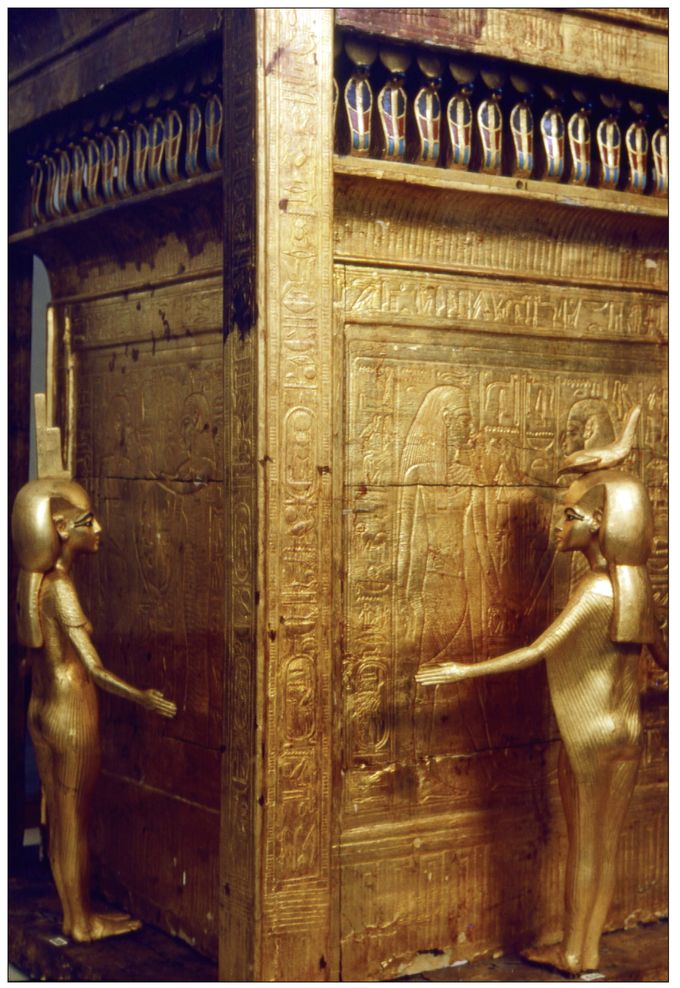

14. The goddesses Isis (left: west) and Serket (south) stand with outstretched arms to protect the gilded canopic chest containing Tutankhamen's preserved internal organs. The goddesses Nephthys (east) and Neith (north) protect the other two sides.

Â

15. Tutankhamen, wearing the White Crown of southern Egypt, and carrying the staff and flail which denote his royal authority, stands on the back of a leopard (representing the south). This statue is one of two depicting the king's control over the natural world: two companion pieces show Tutankhamen wearing the red crown and harpooning in a boat (representing the Delta marshes).

Â

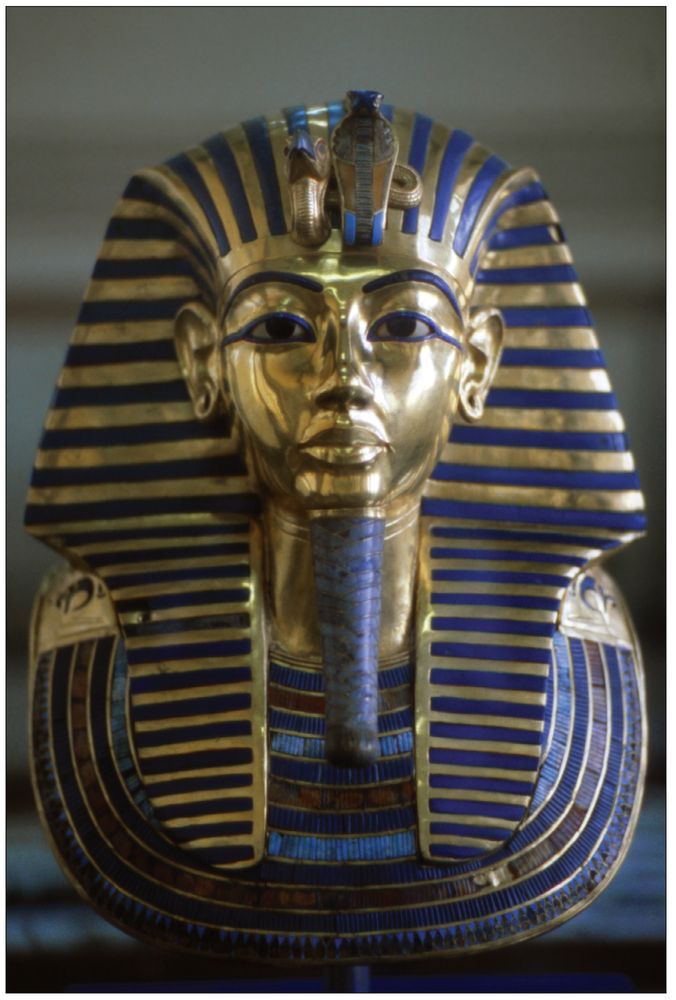

16. The golden face of Tutankhamen has become, for many, the defining image of ancient Egypt.

Much to Carter's disappointment, Derry was unable to determine how Tutankhamen had died. Some causes of death â those, such as smallpox, which left obvious signs on the body â could be excluded, but that hardly narrowed the field. For many years it was generally accepted â for no apparent reason â that Tutankhamen had died of tuberculosis. TB was finally ruled out as a cause of death when Harrison's X-ray of the king's back indicated that the epiphyseal plates were still in place.

As early as 1923, Mace had proposed a more dramatic scenario. Tutankhamen, too young to die a natural death, had perhaps been murdered by his successor, Ay:

The rest is pure conjecture ⦠We have reason to believe that he was little more than a boy when he died, and that it was his successor, Eye [Ay], who supported his candidature to the throne and acted as his

advisor during his brief reign. It was Eye, moreover, who arranged his funeral ceremonies, and it may even be that he arranged his death, judging that the time was now ripe for him to assume the reins of government himself.

38

advisor during his brief reign. It was Eye, moreover, who arranged his funeral ceremonies, and it may even be that he arranged his death, judging that the time was now ripe for him to assume the reins of government himself.

38

In theory, this is a sustainable idea. Some kings were indeed assassinated by their subjects. Their deaths were not the work of political fanatics or random madmen, but the result of elaborate conspiracies hatched in the royal harem, where ambitious mothers and their equally ambitious sons schemed to divert the succession away from the intended heir. The best known of these plots resulted in the death of the 20th Dynasty Ramesses III, and was followed by a trial which saw the execution or forced suicide of all involved. An earlier, tolerably well-documented conspiracy involved the assassination of the founder of the 12th Dynasty, Amenemhat I. Regicide, therefore, cannot be automatically ruled out. But it is hard to see why anyone should have wished to murder Tutankhamen. His reign was slowly but surely correcting the chaos of the Amarna age, and there is no obvious sign that he was doing anything to upset anyone. More to the point, those closest to the king â the people most likely to kill him â had the opportunity to block his elevation to the throne when he inherited as a child. Why wait until the child became a man?

Other books

The Field of Fight: How We Can Win the Global War Against Radical Islam and Its Allies by Lieutenant General (Ret.) Michael T. Flynn, Michael Ledeen

Only for a Night (Lick) by Naima Simone

Confessions of a Backup Dancer by Tucker Shaw

The Boyfriend Experience by Michaela Wright

Bride Who Fell in Love with Her Husband by Cheryl Ann Smith

Falling for the Wingman (The Kelly Brothers, Book 3) by McHugh, Crista

9781631054099GracefulAcceptanceBeck by Paloma Beck

Jezebel by Koko Brown

Red Cell Seven by Stephen Frey

Kill School: Slice by Karen Carr