Tutankhamen (22 page)

Authors: Joyce Tyldesley

An entry in Carter's notebook, dated 1 October 1925, reveals that he originally intended to re-wrap the mummy: âthis scientific examination should be carried out as quietly and reverently as possible, but ⦠I should delay re-wrapping the mummy until I knew whether the Ministers would like [to] inspect the royal remains'. His diary for 23 October 1926 suggest that this was done: âThe first outermost coffin, containing the King's Mummy, finally re-wrapped, was lowered into the sarcophagus this morning.' Yet in 1968 a team led by Ronald Harrison, Professor of Anatomy at Liverpool University, opened the sealed sarcophagus to find Tutankhamen unreconstructed and still lying on his sand tray. The Liverpool team took a skin sample and, as they had been refused permission to remove Tutankhamen from his tomb, used a slightly outmoded portable X-ray scanner to examine his remains.

Their work was filmed, and broadcast on British television in 1969, but, although articles by Harrison were published in

Buried History

and

Antiquity

, the radiographs were never published in the medical literature.

26

Ten years later a third examination, conducted by James E. Harris, Chairman of the Department of Orthodontics at the University of Michigan, again X-rayed the king, concentrating on his head and teeth.

27

It was apparent at this examination that Tutankhamen was deteriorating; there was damage to the ears, his skin had darkened, and his eyes had collapsed inwards.

Their work was filmed, and broadcast on British television in 1969, but, although articles by Harrison were published in

Buried History

and

Antiquity

, the radiographs were never published in the medical literature.

26

Ten years later a third examination, conducted by James E. Harris, Chairman of the Department of Orthodontics at the University of Michigan, again X-rayed the king, concentrating on his head and teeth.

27

It was apparent at this examination that Tutankhamen was deteriorating; there was damage to the ears, his skin had darkened, and his eyes had collapsed inwards.

The most recent work on Tutankhamen's remains has been performed as part of an extensive, ongoing programme of New Kingdom mummy studies by a Cairo-based team of experts under the leadership of Dr Zahi Hawass, then Chairman of the Supreme Council of Antiquities. This team has had access to a full range of modern analytical techniques, including DNA tests and computerised tomography (CT)Â scans. In 2005 Tutankhamen was scanned, and over 1,700 images were used to create a 3D reconstruction of his body.

28

In 2007 he was transferred to a new glass coffin with controlled temperature and humidity. There he rests today; the only king (as far as we know) to lie in his own tomb in the Valley of the Kings.

The Derry Autopsy28

In 2007 he was transferred to a new glass coffin with controlled temperature and humidity. There he rests today; the only king (as far as we know) to lie in his own tomb in the Valley of the Kings.

The Times, 14 November 1923

Luxor: Nov 12 â The mummy of Pharaoh Tutankhamen was taken out of its wrappings today. The body was found covered with gold, with stars of gold on the heart and lungs. A large golden dagger was with the body. It is expected that an official communiqué will be published tomorrow â Reuter.

Tutankhamen's bandaged feet had sustained some damage from

rubbing against the sides of his innermost coffin. This damage was, however, insignificant when compared to the damage caused by the charring within the bandages, which made it impossible to make a full and proper record of the wrappings. Carter estimated that the embalmers had employed sixteen layers of bandages, and that different grades of linen had been used, with the best â used for the innermost and outermost layers â resembling finest cambric. The limbs had been wrapped individually, as had the fingers and toes; the abdomen had been packed with linen sheets impregnated with resin, and the head had been topped by a curious pad of wadded linen whose conical shape reminded Carter of a crown. As far as Carter could tell, âthe mode of binding was as usually practised upon mummies of the New Empire'. However, âwhenever it was possible to discern details of [the] method of wrapping, the evidence was suggestive of hastiness â that was the consensus of opinion among the scientific element present'.

29

rubbing against the sides of his innermost coffin. This damage was, however, insignificant when compared to the damage caused by the charring within the bandages, which made it impossible to make a full and proper record of the wrappings. Carter estimated that the embalmers had employed sixteen layers of bandages, and that different grades of linen had been used, with the best â used for the innermost and outermost layers â resembling finest cambric. The limbs had been wrapped individually, as had the fingers and toes; the abdomen had been packed with linen sheets impregnated with resin, and the head had been topped by a curious pad of wadded linen whose conical shape reminded Carter of a crown. As far as Carter could tell, âthe mode of binding was as usually practised upon mummies of the New Empire'. However, âwhenever it was possible to discern details of [the] method of wrapping, the evidence was suggestive of hastiness â that was the consensus of opinion among the scientific element present'.

29

As Derry picked away the bandages piece by piece, jewellery, amulets and clothing started to appear between the various layers. There were over 150 amulets, each intended to help the king on his journey to the afterlife. Tutankhamen wore bracelets on each arm (seven on the right and six on the left), rings on his fingers and an assortment of collars and pectorals on his chest. There were gold finger and toe stalls and a pair of golden sandals on his feet. A golden apron, or kilt, extended from his waist to his knees and two daggers, one of gold and one of that most exciting of new metals, iron, were attached to girdles. A beautiful, yet simple, golden diadem encircled Tutankhamen's head; beneath this a gold band held a fragile linen

khet

(bag-shaped) headdress in place. Under the headdress came several layers of bandaging, and finally a close-fitting beaded skullcap secured by another gold band. The linen of the cap had decayed, leaving the blue and red glass and gold beads in place. As this was clearly too fragile to remove, it was consolidated with paraffin wax and left in place. Today it has disappeared. It seems unlikely that it could have been stolen

(not as an intact piece, anyway), and it is possible that the beads have simply fallen from the head.

khet

(bag-shaped) headdress in place. Under the headdress came several layers of bandaging, and finally a close-fitting beaded skullcap secured by another gold band. The linen of the cap had decayed, leaving the blue and red glass and gold beads in place. As this was clearly too fragile to remove, it was consolidated with paraffin wax and left in place. Today it has disappeared. It seems unlikely that it could have been stolen

(not as an intact piece, anyway), and it is possible that the beads have simply fallen from the head.

Tutankhamen's body measured 1.63m long. Allowing for slight shrinking during mummification, this suggested that he may have stood 1.67m tall: the same height as the two guardian statues who guarded the doorway to the Burial Chamber. His arms had been flexed at the elbow and folded over his stomach, the left arm above the right. A âragged' embalming wound, just 8.6cm long, was situated, as expected, on the left side of the body running from the navel to the hip bone. Curiously, there was no embalming plate to cover and magically repair this wound, but an oval gold plate was discovered in the bandages on the left side of the body. Examining Tutankhamen's genitals â the scrotum flattened by the embalming process, and the penis (50mm in length) bound in the erect position â Derry could not see any pubic hair and was unable to determine if the king had been circumcised.

The skin on the king's body was greyish in colour, brittle and cracked; skin and flesh together were just 2 â 3mm deep, and could be easily lifted away from the bone. The skin on his face, which had been protected by the funerary mask, was darker in tone and marked with white natron spots. There was a large lesion or scab on his left cheek, over the jawbone near the ear. Tutankhamen was beardless â he had been buried with a full shaving kit, which had been stolen by robbers, leaving only the label behind â and his shaven head was covered in a white substance which Derry identified as fatty acid. His left earlobe bore a wide (7.5mm) piercing but was empty; his right earlobe was missing and was presumed to have come away with the bandages. His eyes were part open, his eyelashes still in place and his lips slightly parted to reveal the prominent front teeth which are observable in other 18th Dynasty royal mummies. His nose, which had been flattened by the bandages, was plugged with linen impregnated with resin. To Carter, Tutankhamen appeared âof a type exceedingly refined and cultured. The face has beautiful and well-formed features. The

head shows strong structural resemblance to Akh-en-aten.'

30

By Akhenaten, Carter meant the KV 55 mummy whom we last encountered in Chapter 2. Derry agreed that Tutankhamen's skull had the same distinctive shape, âbroad and flat-topped (platycephalic)', as the KV 55 skull.

31

head shows strong structural resemblance to Akh-en-aten.'

30

By Akhenaten, Carter meant the KV 55 mummy whom we last encountered in Chapter 2. Derry agreed that Tutankhamen's skull had the same distinctive shape, âbroad and flat-topped (platycephalic)', as the KV 55 skull.

31

Derry noted that Tutankhamen's right upper and lower wisdom teeth âhad just erupted into the gum and reached to about half the height of the 2nd molar. Those on the left side could not be seen easily, but they appeared to be in the same stage of eruption.'

32

This is a curious observation for him to have made. Tutankhamen's closed mouth could not have been forced open without causing serious damage and without the use of X-ray technology, Derry could not have seen Tutankhamen's back teeth. This, combined with his statement that the skull was empty apart from its coating of resin (something that would not have been apparent with the nose-plugs in place), led Leek, himself a dentist well experienced in the investigation of ancient remains, to deduce that Derry must have cut into the head. Using a standard autopsy technique he probably made an incision beneath the chin, passing around the inner border of the jaw and continuing upwards to the floor of the mouth. The damage must then have been repaired with resin.

33

32

This is a curious observation for him to have made. Tutankhamen's closed mouth could not have been forced open without causing serious damage and without the use of X-ray technology, Derry could not have seen Tutankhamen's back teeth. This, combined with his statement that the skull was empty apart from its coating of resin (something that would not have been apparent with the nose-plugs in place), led Leek, himself a dentist well experienced in the investigation of ancient remains, to deduce that Derry must have cut into the head. Using a standard autopsy technique he probably made an incision beneath the chin, passing around the inner border of the jaw and continuing upwards to the floor of the mouth. The damage must then have been repaired with resin.

33

However it was obtained, this dental evidence, combined with bone analysis (the examination of the epiphyses, or growth plates at the end of the long bones), indicated that Tutankhamen had died at between seventeen and nineteen years of age.

The Harrison and Harris ExaminationsAgreeing with Derry, the Liverpool team estimated that Tutankhamen had died aged eighteen to twenty-two. This has occasionally been disputed â Leek suggested that he may have been as young as sixteen; Harris that he may have been as old as twenty-seven â but today it is widely accepted that Tutankhamen was approximately eighteen years old at death.

Â

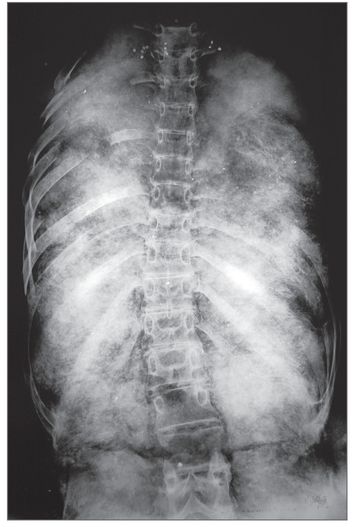

14. Harrison X-ray of Tutankhamen's thorax, showing cut ribs on the right side and broken ribs on the left side. Most of the rib fragments are missing along with the entire front of the thorax and the sternum. At the top, several beads can be seen; these are presumably from the beaded vest which was originally on the body, and which was perhaps used to cover the accidental damage and the wholesale destruction of the thorax by the embalmers.

Â

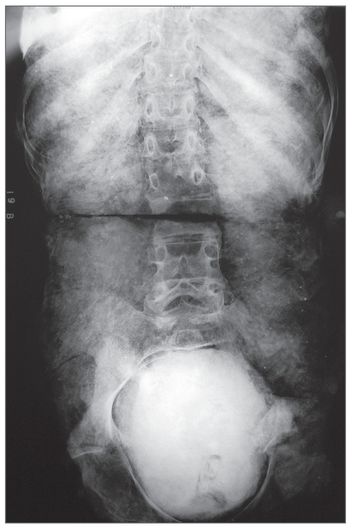

15. Harrison X-ray of the lower part of Tutankhamen's torso showing the dense packing in the pelvic cavity (presumably resin-soaked linen) and the destruction of the left side of the bony pelvis with many pieces missing. This is possibly the result of a âfatal accident'. It is also possible to see packing in the lower part of the thorax and the zone of damage where Derry cut the body in two.

Â

16. Harrison X-ray of the base of Tutankhamen's skull; the line of resin is visible.

The skin sample showed that Tutankhamen and the KV 55 mummy shared the same, relatively rare, blood group (A2 with antigens MN present); in the same analysis, Akhenaten's grandmother Thuya was found to be A2N.

34

Harris's measurements later confirmed Derry's recognition of a close similarity in craniofacial morphology between Tutankhamen and KV 55 (and Tuthmosis IV, father of Amenhotep III). This similarity was strong enough to suggest that Tutankhamen and KV 55 were either brothers or father and son.

34

Harris's measurements later confirmed Derry's recognition of a close similarity in craniofacial morphology between Tutankhamen and KV 55 (and Tuthmosis IV, father of Amenhotep III). This similarity was strong enough to suggest that Tutankhamen and KV 55 were either brothers or father and son.

The Harrison X-rays confirmed that Tutankhamen's head had been part-filled with resin. Two distinct resin layers were observable and, as these were at right angles to each other, it seems that one must have been introduced when the body lay supine, the other when the head was tipped backwards or, more unlikely, the entire body hung

upside down. A small piece of bone was identified in the skull cavity; it seemed likely that this was a fragment of the shattered ethmoid bone, and on the BBC film Harrison gave the opinion that it was a post-mortem artefact. However, closer examination of his X-rays has shown that the ethmoid bone was still intact in 1969 (although it had sustained some damage by 2005). This has led Connolly to suggest that Tutankhamen's brain was not extracted in the conventional manner, but had liquefied and trickled down his nose.

35

upside down. A small piece of bone was identified in the skull cavity; it seemed likely that this was a fragment of the shattered ethmoid bone, and on the BBC film Harrison gave the opinion that it was a post-mortem artefact. However, closer examination of his X-rays has shown that the ethmoid bone was still intact in 1969 (although it had sustained some damage by 2005). This has led Connolly to suggest that Tutankhamen's brain was not extracted in the conventional manner, but had liquefied and trickled down his nose.

35

Other books

The Iron Tempest by Ron Miller

FlavorfulSeductions by Patti Shenberger

If Nuns Ruled the World by Jo Piazza

Wild Sorrow by AULT, SANDI

Must Be Love by Cathy Woodman

White Tombs by Christopher Valen

Prue's Promises [Submissive Sirens 3] (Siren Publishing Allure) by Charlotte Smith

Pinkerton's Sister by Peter Rushforth

Satan's Forge (Star Sojourner Book 5) by Kilczer, Jean

Storybook Dad (Harlequin American Romance) by Bradford, Laura