Tutankhamen (38 page)

Authors: Joyce Tyldesley

Carter's reply was immediate and precise.

The piece mentioned belongs like all other pieces belonging tomb in number four to material found in filling of passage STOP They are

noted on plan in group numbers but not yet fully registered on index STOP

9

noted on plan in group numbers but not yet fully registered on index STOP

9

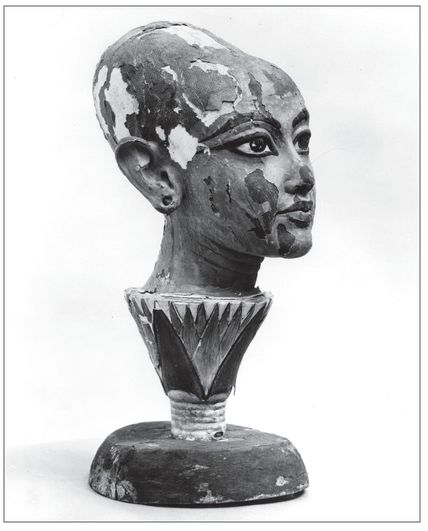

He followed up with an explanatory letter. The head had been recovered amid the debris blocking the passageway, in a very fragile condition. It had been conserved, then put to one side at a time when KV 4 was the only tomb available for storage. It had then, presumably, been forgotten, as Carter's description of the contents of the passageway in the 1923 publication omits any mention of it. It is included, and illustrated as Plate I, in the 1933 publication. Carter ended his letter asserting his annoyance that such a valuable item should have been sent off to Cairo without proper preparation for the journey.

This explanation â an eminently reasonable one, given the vast amount of material that Carter had to deal with â was accepted without further question, and the matter was officially dropped, leaving Lacau and Carter closer allies than they had ever been. It seems likely that Lacau was now starting to feel some resentment over the degree of control that Morcos Bey Hanna was imposing on what he regarded as his own domain. However it left a lingering doubt over the accuracy of Carter's record keeping and, in some minds, over his honesty.

10

10

It was almost certainly Carter who came up with the bright idea that excavation expenses â including his own salary â might be defrayed by buying good antiquities cheaply and selling them on at a handsome profit. This appealed to the gambler in Carnarvon. However, despite dealings with the British Museum and the Metropolitan Museum, among others, relatively little money was raised from the scheme, as Carnarvon, who was a collector as well as a dealer, was unable to resist keeping many of the purchases for his own collection. By the time of his death the Carnarvon collection, housed at Highclere, was one of

the finest private collections of Egyptian antiquities in the world.

the finest private collections of Egyptian antiquities in the world.

Â

22. Tutankhamen as Re emerging from a lotus, initially discovered âin filling of passage' and later re-discovered in KV 4.

Carnarvon's will left his antiquities to his wife, Almina. As Lady Carnarvon's family money had financed the collection this does not seem entirely unreasonable, although Carnarvon's heir, Lord Porchester, may have viewed things differently. Lady Carnarvon had an expensive lifestyle and very little interest in ancient Egyptian art. Carnarvon realised that she would almost certainly sell his collection and so, in a codicil to his will, he advised:

Should she find it necessary to sell the collection, I suggest that the nation â i.e. the British Museum â be given the first refusal at £20,000, far below its value, such sum however, to be absolutely hers, free of all duties. Otherwise I would suggest that the collection be offered to the Metropolitan, New York, Mr Carter to have charge of the negotiations and to fix the price.

Should my wife decide to keep the collection I leave it absolutely to her whether she leaves it to my son or to the nation or to Evelyn Herbert. I suggest, however, that she consult Dr Gardiner and Mr Carter on the subject.

11

11

The specified price of £20,000 was far below the market value of the collection, estimated by Carter to be in the region of £35,000, and Lady Carnarvon was reluctant to take her husband's advice. Initially she planned to dispose of the collection by putting it up for auction, but Carter persuaded her that this was not a good idea. It is not clear whether or not the collection was ever offered to the British Museum: there are persistent rumours that they were given first refusal for £20,000 if they would accept by 4 p.m. that same day (which they evidently were unable to do), but there is nothing to back up this story. The collection was eventually sold to the Metropolitan Museum for $145,000; then little more than the £20,000 suggested by Carnarvon.

In 1924 Carter was charged with packing the collection for deposit in the Bank of England. He listed 1,218 objects, or groups of objects, then added the comment âA few unimportant antiquities not belonging to the above series I left at Highclere'.

12

The 6th Earl, a man with a strong aversion to Egyptology in general and Tutankhamen in particular, was not interested in these pieces. A few were dotted around the house as ornaments, but most â over 300 objects â were stored in two cupboards set into the thick wall between the drawing room and smoking room.

13

Gradually these pieces were forgotten until only Robert Taylor, butler to the 6th Earl, knew that they were there. Taylor had rediscovered the collection in 1972, while making plans for a party, but had thought nothing of it. In 1987 the death of the 6th Earl made it necessary to create an inventory of Highclere. Taylor came out of retirement to help the 7th Earl, and was able to show him the cupboards. Astonished, the 7th Earl ordered a search of the castle,

and more objects came to light; the housekeeper's room, for example, yielded a fragment of stone carved with hieroglyphs. This forgotten collection includes objects dating from the Middle Kingdom to the Ptolemaic Period, and the legally obtained share of Carnarvon's earliest work in Thebes and the Delta, including pieces recovered from the tomb of Amenhotep III. None of the pieces has any connection with Tutankhamen. The circumstances of their re-discovery, however, led to entirely incorrect speculation that these might be hidden Tutankhamen finds.

12

The 6th Earl, a man with a strong aversion to Egyptology in general and Tutankhamen in particular, was not interested in these pieces. A few were dotted around the house as ornaments, but most â over 300 objects â were stored in two cupboards set into the thick wall between the drawing room and smoking room.

13

Gradually these pieces were forgotten until only Robert Taylor, butler to the 6th Earl, knew that they were there. Taylor had rediscovered the collection in 1972, while making plans for a party, but had thought nothing of it. In 1987 the death of the 6th Earl made it necessary to create an inventory of Highclere. Taylor came out of retirement to help the 7th Earl, and was able to show him the cupboards. Astonished, the 7th Earl ordered a search of the castle,

and more objects came to light; the housekeeper's room, for example, yielded a fragment of stone carved with hieroglyphs. This forgotten collection includes objects dating from the Middle Kingdom to the Ptolemaic Period, and the legally obtained share of Carnarvon's earliest work in Thebes and the Delta, including pieces recovered from the tomb of Amenhotep III. None of the pieces has any connection with Tutankhamen. The circumstances of their re-discovery, however, led to entirely incorrect speculation that these might be hidden Tutankhamen finds.

Howard Carter, too, left a collection of antiquities. His will was a simple one. Harry Burton and Bruce Ingram, editor of the

Illustrated London News

(the one British publication which had retained its interest in Tutankhamen) were named as his executors. His house on the West Bank and all its contents were to go to the Metropolitan Museum and, after sundry minor bequests including one to his loyal servant Abdel-Asl Ahmad Said, the remainder of his estate was to go to his niece, Phyllis Walker, the daughter of his sister Amy. Here Carter, like Carnarvon before him, had a word of advice to offer:

Illustrated London News

(the one British publication which had retained its interest in Tutankhamen) were named as his executors. His house on the West Bank and all its contents were to go to the Metropolitan Museum and, after sundry minor bequests including one to his loyal servant Abdel-Asl Ahmad Said, the remainder of his estate was to go to his niece, Phyllis Walker, the daughter of his sister Amy. Here Carter, like Carnarvon before him, had a word of advice to offer:

⦠and I strongly recommend to her that she consult my Executors as to the advisability of selling any Egyptian or other antiquities included in this bequest.

14

14

Miss Walker sensibly took this advice and consulted Burton, Newberry and Gardiner. All reached the same conclusion â that Carter's private collection included objects from Tutankhamen's tomb. The items, as listed by Burton for Engelbach, the new Head of the Egyptian Antiquities Service, were as follows:

1 green-blue glass headrest

1 large shawabti [

shabti

: servant figure], green faience

1 pair lapis shawabti

1 small libation glass

1 sepulchral dummy cup, faience

1 ankle amulet

9 gold-headed nails

3 gold ornaments for harness

1 metal âtennon'

1 large shawabti [

shabti

: servant figure], green faience

1 pair lapis shawabti

1 small libation glass

1 sepulchral dummy cup, faience

1 ankle amulet

9 gold-headed nails

3 gold ornaments for harness

1 metal âtennon'

While some of these items were of negligible commercial or historical importance, the inscribed glass headrest was a unique and correspondingly valuable item. It is not clear how or when these objects had been acquired, or who took them from the tomb, and it is entirely possible that some, if not all, had been removed by Carter from Carnarvon's private collection immediately prior to its sale to the Metropolitan Museum. Margaret Orr, daughter of Carter's fellow excavator and co-author Arthur Mace, is on record as stating that her mother, Winifred, did not approve of Carter because he openly displayed antiquities (presumably taken from the tomb; though this cannot be proven) in his London home.

15

15

Burton and Ingram now found themselves in a difficult, and potentially highly embarrassing situation. How could the objects be returned to Egypt with a minimum of fuss? Initially it was hoped that they could be returned in the âdiplomatic bag'. With Britain on the brink of war, however, the Foreign Office was reluctant to co-operate. Indeed, Under-Secretary Laskey was prompted to observe: âI suppose the objects must be returned ⦠My own inclination is to have them dropped in the Thames.'

16

Eventually the objects were handed to the Egyptian Consulate in London â where they would remain throughout the war â then in 1946 returned by air to King Farouk, who personally presented them to Cairo Museum.

16

Eventually the objects were handed to the Egyptian Consulate in London â where they would remain throughout the war â then in 1946 returned by air to King Farouk, who personally presented them to Cairo Museum.

The objects in Carter's collection â minus the Tutankhamen objects â were valued for probate at just £1,093. They were sold through the London dealers Spink, or via Ingram and Burton, and eventually made their way into museum collections including the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, and, inevitably, the Metropolitan Museum, New York.

17

17

In 1978 Thomas Hoving published

Tutankhamun: The Untold Story

. Hoving was no alternative historian or fiction writer; he was the larger-than-life Director of the Metropolitan Museum (1967 â 77). His obituaries would refer to him as a âcharismatic showman and treasure hunter ⦠one of the breed of brash, self-mythologising leaders', while in his autobiography, which is in some ways reminiscent of Budge's far earlier autobiography, he described his role as âpart gunslinger, ward heeler, legal fixer, accomplice smuggler, anarchist and toady'.

18

Despite its title, his book promised to reveal not the untold truth about Tutankhamen, but the untold truth behind his discovery. It is, by anyone's standards, a curious book for a museum director to have written:

Tutankhamun: The Untold Story

. Hoving was no alternative historian or fiction writer; he was the larger-than-life Director of the Metropolitan Museum (1967 â 77). His obituaries would refer to him as a âcharismatic showman and treasure hunter ⦠one of the breed of brash, self-mythologising leaders', while in his autobiography, which is in some ways reminiscent of Budge's far earlier autobiography, he described his role as âpart gunslinger, ward heeler, legal fixer, accomplice smuggler, anarchist and toady'.

18

Despite its title, his book promised to reveal not the untold truth about Tutankhamen, but the untold truth behind his discovery. It is, by anyone's standards, a curious book for a museum director to have written:

⦠the full story is not altogether the noble, waxen, proper and triumphant tale so familiar to us. The truth is also full of intrigue, secret deals and private arrangements, covert political activities, skulduggery, self-interest, arrogance, lies, dashed hopes, poignance and sorrow â a series of events disfigured by human frailties that led to a fundamental and enduring change in the conduct of archaeology in Egypt.

19

19

Hoving wrote from the American rather than the British or Egyptian perspective, making full use of the Metropolitan's previously unpublished Tutankhamen archives. Today we regard Tutankhamen as an Egyptian king and a British discovery, but in the 1920s many Americans, labouring under the misapprehension that Carter was not only American but also a member of the Metropolitan Museum staff,

thought otherwise. Only when they heard Carter speak, on his hugely successful 1924 lecture tour, did they realise their mistake:

thought otherwise. Only when they heard Carter speak, on his hugely successful 1924 lecture tour, did they realise their mistake:

Mr Carter spoke to his first public audience yesterday in Carnegie Hall of the âSahawra' desert, he âashuahed' them on âbehawf ' of his colleagues of various reassuring things about Tutankhamen. Thirty-four years of grubbing about for ancient tombs have intensified his British vocal mannerisms, so that the person who started the report that Carter was an American should be captured, stuffed and placed in a glass case and labelled the most inaccurate of human observers.

20

20

Other books

Tapestry of the Past by Alvania Scarborough

Exquisite Redemption (Iron Horse MC Book 3) by Ann Mayburn

Coveted by Stacey Brutger

Her Passionate Plan B by Dixie Browning

Electric City: A Novel by Elizabeth Rosner

southern ghost hunters 02 - skeleton in the closet by fox, angie

Realm Wraith by Briar, T. R.

Always a Scoundrel by Suzanne Enoch

Promise of Blood by Brian McClellan

Tormented (Evolution Series Book 2) by Carrero, Kelly