Tutankhamen (29 page)

Authors: Joyce Tyldesley

Tutankhamen's Mother: The Younger Lady?

Tutankhamen's Children?

Tutankhamen's Children?

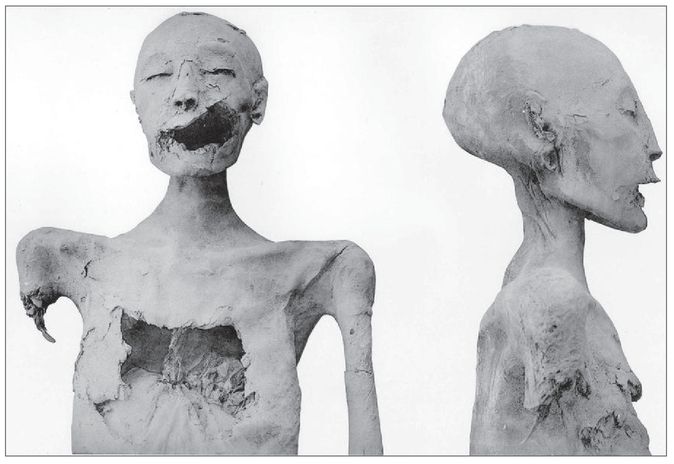

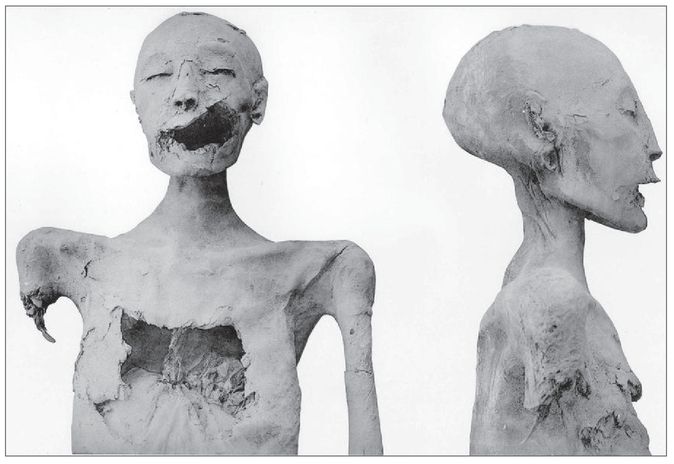

The Younger Lady (KV 35YL), recovered in a side chamber in the cache tomb of Amenhotep II, has a confused recent history. Loret, perhaps misled by the mummy's bald head, initially identified it as a young man. Soon after, the âyoung man' was recognised as female. Marianne Luban was the first to propose, on the grounds of skull shape, bone structure, the shaven head and evidence of ear piercing, that this mummy may be Nefertiti.

44

But when a team from York University carried out a non-invasive examination of the mummy, and came to the same conclusion, the situation was almost immediately complicated by the publication of a report from the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities, which stated, on the basis of DNA testing, that the âYounger Lady' was male.

45

It now seems that this analysis may have been performed on a detached arm, found in the same chamber, as the most recent testing has confirmed that the mummy is indeed female.

44

But when a team from York University carried out a non-invasive examination of the mummy, and came to the same conclusion, the situation was almost immediately complicated by the publication of a report from the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities, which stated, on the basis of DNA testing, that the âYounger Lady' was male.

45

It now seems that this analysis may have been performed on a detached arm, found in the same chamber, as the most recent testing has confirmed that the mummy is indeed female.

The most recent DNA analysis performed by the Supreme Council of Antiquities research team has suggested that the Younger Lady was both Tutankhamen's mother and a previously unknown sister of KV

55/Akhenaten, although a member of the team has since been quoted in the German press as stating that she may equally well be the granddaughter of Tiy (here identified as the Elder Lady: KV 35EL) rather than her daughter.

46

Finally they suggest that the Younger Lady was killed by a sharp blow to the face, although others believe that the undeniable damage to the face occurred post-mortem. This identification has provoked intense debate; it is certainly hard to imagine the circumstances where such a prominent woman would go unmentioned in the Amarna record. If she is a sister of Akhenaten, could she be Sitamen? Or, if KV 55 is not in fact Akhenaten, could the Younger Lady be either Meritaten or Ankhesenamen?

55/Akhenaten, although a member of the team has since been quoted in the German press as stating that she may equally well be the granddaughter of Tiy (here identified as the Elder Lady: KV 35EL) rather than her daughter.

46

Finally they suggest that the Younger Lady was killed by a sharp blow to the face, although others believe that the undeniable damage to the face occurred post-mortem. This identification has provoked intense debate; it is certainly hard to imagine the circumstances where such a prominent woman would go unmentioned in the Amarna record. If she is a sister of Akhenaten, could she be Sitamen? Or, if KV 55 is not in fact Akhenaten, could the Younger Lady be either Meritaten or Ankhesenamen?

Â

20. The âYounger Lady' discovered in the Amenhotep II cache of royal mummies.

Tutankhamen's Treasury yielded a plain and unassuming box housing two miniature anthropoid coffins lying side by side and head to foot, one measuring 49.5cm and the other 57.7cm in length. The coffins had been tied shut with linen ribbons around the neck, waist and ankles, and sealed with the necropolis seal. Both coffins were made of wood, both had been painted with resin, and both bore conventional inscriptions naming the deceased simply as âOsiris'. They barely fitted into their box and, in a reflection of what happened to Tutankhamen's own coffin, it had proved necessary to cut away the toes of the larger coffin in order to shut the lid. This lid, which had originally been tied and sealed in place, had been displaced in antiquity. Each coffin contained an inner coffin covered in gold foil, and each of these held a tiny, perfectly bandaged mummy.

The first mummy wore a golden cartonnage funerary mask that was too large for its head. It was unwrapped by Carter, then autopsied by Derry, who identified it as the body of a premature girl, measuring 25.75cm from the vertex of the head to the heels.

47

Although there was no sign of an abdominal incision, and therefore no sign of how preservation had been achieved, she was in good condition even though her grey skin was somewhat brittle. She had been wrapped with her arms fully extended and her hands resting on the front of her thighs. She had neither eyelashes nor eyebrows, but she did have fine hair on her head, which Derry thought was probably the remains of lanugo (fine baby hair). A portion of the umbilical cord was still attached. Derry estimated that this child had died at five months' gestation.

47

Although there was no sign of an abdominal incision, and therefore no sign of how preservation had been achieved, she was in good condition even though her grey skin was somewhat brittle. She had been wrapped with her arms fully extended and her hands resting on the front of her thighs. She had neither eyelashes nor eyebrows, but she did have fine hair on her head, which Derry thought was probably the remains of lanugo (fine baby hair). A portion of the umbilical cord was still attached. Derry estimated that this child had died at five months' gestation.

The second mummy was also well bandaged, but lacked a golden mummy mask. It seems likely that the miniature mask, recovered by Davis in his 1907 excavation of Tutankhamen's embalming refuse (KV 54), and now housed in Cairo Museum (JE 39711), originally came from this mummy, even though it is slightly too small to have fitted neatly on the wrapped head.

48

Derry unwrapped this mummy himself.

He discovered a second baby girl, measuring 36.1cm from the vertex of the head to the heels. Although there was an obvious embalming incision, and the body and skull cavity had been packed with resin-impregnated linen, she was less well preserved than the other mummy. Her extended arms lay beside the thighs. She had eyebrows and eyelashes and her eyes were wide open. Although there was little head hair, Derry felt that this may have come away with the bandages. There was no umbilical cord but Derry felt, from the condition of the navel, that this had been cut away rather than withered naturally, suggesting that she was stillborn at approximately seven months' gestation. Harrison, who radiographically re-examined the body, believed the child to have been a stillbirth of eight or nine months' gestation. He suggested that she had suffered Sprengal's deformity of the clavicle in conjunction with spina bifida and lumbar scoliosis.

49

More controversially, it has since been suggested that the two girls may have been stillborn twins, their difference in size being attributed to intrauterine growth discrepancy resulting from Twin â Twin Transfusion syndrome.

50

48

Derry unwrapped this mummy himself.

He discovered a second baby girl, measuring 36.1cm from the vertex of the head to the heels. Although there was an obvious embalming incision, and the body and skull cavity had been packed with resin-impregnated linen, she was less well preserved than the other mummy. Her extended arms lay beside the thighs. She had eyebrows and eyelashes and her eyes were wide open. Although there was little head hair, Derry felt that this may have come away with the bandages. There was no umbilical cord but Derry felt, from the condition of the navel, that this had been cut away rather than withered naturally, suggesting that she was stillborn at approximately seven months' gestation. Harrison, who radiographically re-examined the body, believed the child to have been a stillbirth of eight or nine months' gestation. He suggested that she had suffered Sprengal's deformity of the clavicle in conjunction with spina bifida and lumbar scoliosis.

49

More controversially, it has since been suggested that the two girls may have been stillborn twins, their difference in size being attributed to intrauterine growth discrepancy resulting from Twin â Twin Transfusion syndrome.

50

We have no explanation for these bodies and, with no other intact royal tomb, no parallel to consider. But, although it is entirely possible that they are Tutankhamen's baby sisters, or even that they are included in the tomb as ritual objects rather than family members, it is difficult to escape the gut-reaction that these are two stillborn daughters born to Tutankhamen and Ankhesenamen. We don't have Ankhesenamen's body, but the recent genetic analysis conducted by the Supreme Council of Antiquities has indicated that they may be the children of Tutankhamen and an otherwise unidentified 18th Dynasty mummy (KV 21A) recovered from a private tomb in the Valley of the Kings.

51

This is a strange development, unless we are to identify KV 21A, who has previously been assumed to belong to the earlier 18th Dynasty, with Tutankhamen's only known wife, Ankhesenamen. But this cannot be the case, as further examination of the genetic data published by the Egyptian team indicates that the foetuses could not be

the children of Tutankhamen plus any daughter fathered by KV 55 whom they identify as Akhenaten.

52

Either Tutankhamen had one or more unknown wives who were the mothers of the foetuses, or KV 55 is not Akhenaten, father of Ankhesenamen, who is herself the mother of the foetuses, or the foetuses are not immediate family members.

51

This is a strange development, unless we are to identify KV 21A, who has previously been assumed to belong to the earlier 18th Dynasty, with Tutankhamen's only known wife, Ankhesenamen. But this cannot be the case, as further examination of the genetic data published by the Egyptian team indicates that the foetuses could not be

the children of Tutankhamen plus any daughter fathered by KV 55 whom they identify as Akhenaten.

52

Either Tutankhamen had one or more unknown wives who were the mothers of the foetuses, or KV 55 is not Akhenaten, father of Ankhesenamen, who is herself the mother of the foetuses, or the foetuses are not immediate family members.

Did Tutankhamen have any other children? Just two independent, circumstantial and rather weak pieces of evidence have been used to argue that he may have had.

53

The first is a letter written by the Babylonian king Burnaburiash, in which he uses a standard, formal greeting to address â⦠your house, your wives, your childrenâ¦'; it is impossible to assess the importance of what might be a simple slip of the cuneiform stylus. The second is an illustration on an ivory chest, recovered from his tomb, which shows the king and queen in a garden, with two anonymous children nearby. These two children may indeed belong to Tutankhamen and Ankhesenamen; however, they might equally be the king and queen themselves.

53

The first is a letter written by the Babylonian king Burnaburiash, in which he uses a standard, formal greeting to address â⦠your house, your wives, your childrenâ¦'; it is impossible to assess the importance of what might be a simple slip of the cuneiform stylus. The second is an illustration on an ivory chest, recovered from his tomb, which shows the king and queen in a garden, with two anonymous children nearby. These two children may indeed belong to Tutankhamen and Ankhesenamen; however, they might equally be the king and queen themselves.

Tutankhamen was succeeded by Ay. This unlikely choice of heir â at an estimated sixty years of age Ay was already elderly, and can surely have been no more than a caretaker king â is a strong indication that Tutankhamen had no living child to follow him. We might have expected Horemheb, Ay's own far younger successor, to step forward at this point; his title of regent suggests that this may well have been Tutankhamen's intention. But it seems â without being absolutely proven â that in Year 9/10 Tutankhamen's troops were engaged in failing to re-take the Syrian city of Kadesh, which had fallen under the influence of the Hittite king Suppiluliumas.

54

We have few specific details of this campaign, but random carved scenes recovered from Luxor (the probable remains of Tutankhamen's memorial temple), plus tribute scenes carved in the Karnak temple and scenes on the walls of Horemheb's Memphite tomb, suggest that the Egyptians faced a coalition of Syrian-Palestinian forces rather than Hittites. Horemheb played no part in Tutankhamen's funeral arrangements;

presumably, if he was fighting in Syria, he could not return to Thebes in time. But he would subsequently decorate the walls of his memorial temple with scenes of Asiatic campaigns that â if they really happened â were probably conducted entirely during Tutankhamen's reign.

54

We have few specific details of this campaign, but random carved scenes recovered from Luxor (the probable remains of Tutankhamen's memorial temple), plus tribute scenes carved in the Karnak temple and scenes on the walls of Horemheb's Memphite tomb, suggest that the Egyptians faced a coalition of Syrian-Palestinian forces rather than Hittites. Horemheb played no part in Tutankhamen's funeral arrangements;

presumably, if he was fighting in Syria, he could not return to Thebes in time. But he would subsequently decorate the walls of his memorial temple with scenes of Asiatic campaigns that â if they really happened â were probably conducted entirely during Tutankhamen's reign.

Confirmation of the lack of royal sons comes from a letter recovered from the royal archives of the Hittite capital, Boghaskoy (Anatolia). The letter is written in cuneiform âwedge' text, the standard text used in 18th Dynasty diplomatic correspondence:

⦠But when the people of Egypt had heard of the attack on Amka, they were afraid. And since, in addition, their lord Nibkhururriya had died, therefore the queen of Egypt, who was Dahamunzu, sent a messenger to my father and wrote to him thus: âMy husband has died. A son I have not. But to thee, they say, the sons are many. If thou woulds give me one son of thine, he would become my husband. Never shall I pick out a servant of mine and make him my husband ⦠I am afraid.' When my father heard this, he called forth the Great Ones for council, saying âSuch a thing has never happened to me in my whole life!' So it happened that my father sent forth to Egypt Hattusaziti, the chamberlain (with this order): âGo and bring thou the true word back to me. Maybe they deceive me. Maybe (in fact) they do have a son of their lord. Bring thou the true word back to me.'

55

55

At first sight, this is a simple, poignant tale. A widowed queen of Egypt has written to Suppiluliumas, asking him to send one of his sons as her bridegroom. The king's name, Nibkhururriya, seems to be a Hittite version of Tutankhamen's prenomen, Nebkheperure. The name of the letter writer, âDahamunzu', is a phonetic version of the standard Egyptian queen's title

ta hemet nesu

(king's wife).

56

As Ankhesenamen is Tutankhamen's only prominent wife, it seems that she must be the lonely letter writer. But, here doubts set in. As Suppiluliumas knew, Egyptian princesses did not marry foreigners, and widowed

queens did not re-marry. Ankhesenamen, as the last surviving Amarna princess, would have been next in line for the throne in her own right and, as the earlier 18th Dynasty female pharaoh Hatshepsut had proved, queens could rule unmarried. Furthermore, the Hittites and the Egyptians were not exactly good friends. Ankhesenamen did, however, need a husband if she was to produce the next heir to the throne, and she may have wished to draw the lingering and expensive hostilities with the Hittites to an end. Rather than the simple plea of a helpless woman, is this an intelligent attempt to find a diplomatic solution to two of Egypt's problems?

ta hemet nesu

(king's wife).

56

As Ankhesenamen is Tutankhamen's only prominent wife, it seems that she must be the lonely letter writer. But, here doubts set in. As Suppiluliumas knew, Egyptian princesses did not marry foreigners, and widowed

queens did not re-marry. Ankhesenamen, as the last surviving Amarna princess, would have been next in line for the throne in her own right and, as the earlier 18th Dynasty female pharaoh Hatshepsut had proved, queens could rule unmarried. Furthermore, the Hittites and the Egyptians were not exactly good friends. Ankhesenamen did, however, need a husband if she was to produce the next heir to the throne, and she may have wished to draw the lingering and expensive hostilities with the Hittites to an end. Rather than the simple plea of a helpless woman, is this an intelligent attempt to find a diplomatic solution to two of Egypt's problems?

The canny Suppiluliumas sent his chamberlain to make further enquiries in Egypt. The timing must have been tight â it would have taken many days to make the long journey from Boghaskoy to Memphis and back again, and all the while Egypt would have been waiting for a king to bury Tutankhamen. Many weeks later Hattusaziti returned. He had questioned the queen, and she in turn had sent a terse message via her own envoy Hani:

Why didst thou say âthey deceive me' in this way? Had I a son, would I have written about my own and my country's shame to a foreign land? Thou didst not believe me and hast even spoken thus to me. He who was my husband had died. A son I have not. Never shall I take a servant of mine and make him my husband. I have written to no other country. Only to thee have I written. They say thy sons are many: so give me one of thine. To me he will be husband, but in Egypt he will be king.

57

57

Optimism overcame experience, and Suppiluliumas dispatched a son, Zannanza, who died on route to his wedding. Whether or not this was a natural death is unclear; but it certainly caused a rift in the already lukewarm relationship between Egypt and the Hittites. By the time the artists painted the scenes on the wall of his Burial Chamber,

Tutankhamen's successor was decided and Ay was king of Egypt.

Tutankhamen's successor was decided and Ay was king of Egypt.

It has been suggested that Ankhesenamen would have been desperate to acquire a royal, if foreign, husband because she was appalled at the idea that she would be compelled to marry the elderly Ay, her probable grandfather, to reinforce his right to the throne. This theory, a persistent one in popular literature, is based upon the entirely erroneous âroyal heiress' theory, and is supported by just one dubious piece of evidence: a blue glass ring engraved with the names of Ay and Ankhesenamen.

58

In the event, Ay came to the throne with his longstanding wife Tiye as his consort. We do not see Ankhesenamen again, and her body has never been identified.

58

In the event, Ay came to the throne with his longstanding wife Tiye as his consort. We do not see Ankhesenamen again, and her body has never been identified.

7

RESTORATION

Other books

Paris Is Always a Good Idea by Nicolas Barreau

Vampire Warlords: The Clockwork Vampire Chronicles by Andy Remic

The Late, Lamented Molly Marx by Sally Koslow

The Angel of Highgate by Vaughn Entwistle

Anna's Hope Episode One by Odette C. Bell

The Island of Doves by Kelly O'Connor McNees

An Inconvenient Love (Crimson Romance) by Alexia Adams

Balustrade by Mark Henry

Against the Day by Thomas Pynchon

The Black Moon by Winston Graham