Ultimate Baseball Road Trip (76 page)

Read Ultimate Baseball Road Trip Online

Authors: Josh Pahigian,Kevin O’Connell

Famous Tigers fan Patsy O’Toole made such a ruckus at the ballpark that when he traveled to Washington, D.C., for a World Series game between the Yankees and Senators at Griffith Stadium in 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt found him too obnoxious to bear and requested that O’Toole be relocated to another part of the ballpark. If that’s not one of the most egregious abuses of executive power in US presidential history, then we don’t know what is.

Josh Beat the House

The MGM Grand Detroit Casino is just a ten-minute walk from Comerica. Follow Michigan Avenue across Woodward, then take a left on Third Street and a right onto Abbott and you’ll soon be there. Just be sure to drive if visiting after dark. Actually, driving is a good option anytime, since we had a difficult time finding a walk-up entrance. Like everything in downtown Motown, they’re expecting that you’ll come by car.

We visited The MGM after watching the Yankees beat the Tigers. Though Josh figured the Yankee victory would surely bring him bad karma and resolved to stay away from the roulette table, as soon as he caught a breath of the cold casino air and caught a peek of the cocktail waitresses in bikinis, he perked up.

Kevin went first, bellying up to a table and losing his modest bankroll pretty much immediately. Then Josh picked a table and asked for his trademark purple chips. He employed a system that had served him well in the halcyon days of his gambling youth when he and his college friends would visit Connecticut’s Foxwoods. P.S. Josh has a system for nearly everything.

The system revolves around hedging one’s bets. At a $15 minimum table, the player puts $15 outside on red, then 15 dollar chips inside on 15 different black numbers, thus covering 30 of the 38 possible numbers. Any red number means the player breaks even, 15 black numbers yield a net gain of $6. And the eight remaining black/green numbers result in a loss of $30. And it only takes two hours to make any real money. But conversely, it also takes a great deal of time to lose any money. The system was designed by Josh and Holy Cross pal Rich Hoffman to keep them at the table long enough to consume at least four free drinks, before cashing out.

“You know, Josh,” Kevin said, “if you bet equal number of chips on red and black, or odd and even, you could play this game all night long.”

Josh humbly reminded Kevin that he was still at the table playing while Kevin was broke, watching like a lap dog.

In Detroit, Josh’s system broke down when a cocktail waitress informed him that his rum-and-coke cost $3. Never before had he been asked to pay for a drink while playing. Nonetheless, he played for more than an hour and actually made a few bucks before Kevin reminded him that the road trip car needed to hit the road soon if they were to make it to Cleveland in time for the next day’s game. So he started taking chances. First, he loaded up on Kevin’s lucky numbers, playing 17 and 00, then he took Kevin’s suggestion and played his birthday, twenty-two. A few rolls later, he was up more than $100. After giving half his winnings back, he cashed out up $50. Not a bad hour’s work.

“So this means you’re buying dinner, right?” Kevin asked.

“You betcha,” Josh replied almost too quickly.

“Really?” Kevin gushed.

“No,” Josh laughed.

CHICAGO CUBS,

CHICAGO CUBS,WRIGLEY FIELD

The Friendly Confines

C

HICAGO

, I

LLINOIS

7 MILES TO U.S. CELLULAR FIELD

90 MILES TO MILWAUKEE

285 MILES TO DETROIT

300 MILES TO ST. LOUIS

F

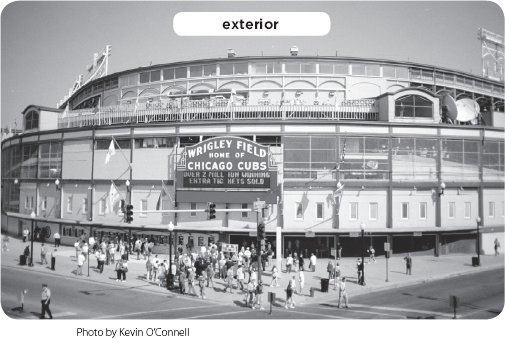

or any student of the game and its history, Wrigley Field is as good as it gets. The weathered green steel of the ballpark’s exterior may not present quite the regal edifice that Yankee Stadium projects to the world, but inside the essence of class abounds—not in a retro, overly done, twenty-first-century way, but subtly, genuinely. Wrigley Field is authentic. And while it may be the

second

oldest ballpark in the Majors, it feels much older than any other existent park—and not just because male fans (and quite possibly female ones too, for all we know) still have to pee in troughs. Unlike its only remaining contemporary, Fenway Park, which has been significantly updated in recent years, Wrigley still offers a strikingly similar environment to the one it provided at its debut in 1914. Sure, it has been renovated to add more seats and there are lights now, but the fact remains that a JumboTron remains conspicuously absent. Also left out are the electronic advertisements, overpowering sound bites, and modern amenities that allegedly make the new parks “fan friendly.” The only sounds inside Wrigley are those emanating from an old-fashioned organ, the crowd, and the unobtrusive PA announcer.

Upon entering “the Friendly Confines,” our attention was drawn to the green grass and red dirt of the field. The focus is where it should be. And watching the game, we felt as though we were sitting in the 1920s. We felt a kinship with our fellow man as we sat elbow-to-elbow celebrating the game we love. If this ain’t heaven, it’s pretty close.

More than just being ancient and reeking with history, Wrigley also exemplifies the vital role a ballpark can play in the American city. Nestled in festive Wrigleyville, this gem of a yard is the cornerstone of a hopping entertainment district. Even when the Cubs are on the road, tourists come to see the ballpark and sample the neighborhood restaurants and saloons. And that is true during wintertime too.

Wrigley was built on the site of a former seminary for the meager cost of $250,000. When it opened it was called Weeghman Park and served as home not to the Cubs, but to the Chicago Whales of the Federal League. The “Fed” folded a year later—no small wonder given the league’s uncanny knack for accepting teams with completely inappropriate nicknames. Whaling in the windy city? What a gas! Or perhaps local history ignores the reality that the humpback once frolicked in Lake Michigan?

In 1915 Charles Weeghman, former owner of the Whales, purchased the National League Cubs and moved them to Weeghman Park. The new digs represented the Cubs’ sixth home since going pro in 1870. Immediately prior to their final move, they’d been at West Side Park on the corner of Polk and Lincoln. Then, on April 20, 1916, the Cubs played their first game at Weeghman, posting a 7–6 win over the Reds. Ten years later, the park was renamed Wrigley Field in honor of new team owner William Wrigley Jr., a chewing-gum magnate who had purchased the team in 1921. The Cubs would remain in the family for sixty years before being sold to the Tribune Company in 1981.

Today, the team is owned by J. Joseph Ricketts, the founder of TD Ameritrade. His son Tom Ricketts is in charge of the team’s day-to-day operations. The deep-pocketed Ricketts have suggested they’d like to work out a deal with the State of Illinois and the City of Chicago to orchestrate a multi-hundred-million-dollar renovation of Wrigley to ensure its longevity. It remains to be seen how much funding will come from the Ricketts’ bankroll and how much will come from taxpayers. Also, still being debated is what exactly the work might entail, and when it might begin.

Kevin:

It would be nice to know this place will be around forever.

Josh:

But if the renovation too drastically changes things …

Kevin:

There’s the rub.

Josh:

Hopefully, they’ll strike the right balance.

Just how old-school are the Cubs? Well, they’re older even than the National League. In 1870 they were founding

members of the National Association. Known as the White Stockings, they had to drop out of that league in 1872 and in 1873 because the Great Chicago Fire destroyed their park, uniforms, and equipment. In 1875 team president William Hulbert led the charge to form a new league, and the National League was born.

Chicago won the first NL championship in 1876, outscoring opponents by more than five runs per game. In the late 1890s and early 1900s the franchise tried on a number of nicknames reflective of the team’s youth, including the “Colts” and “Orphans,” before settling on the Cubs.

In 1906, the early Cubs clashed with the crosstown White Sox in the World Series, which was won by the “Hitless Wonder” Sox in six games. The Cubs rebounded to win the Series in 1907 and 1908, both times against the Tigers. They have not won a World Series since, despite having had seven October opportunities. Their last Series appearance was a little while ago now, though. It played out amidst some controversy in 1945 but we’ll discuss that Series later in the chapter.

For a while the Cubs’ long drought wasn’t quite so ignominious, since two other venerable franchises were working on epic stretches of futility of their own. The White Sox had gone since 1917 without an October Classic victory and, in fact, hadn’t even appeared in a World Series since 1919 when the Black Sox purposely lost. Meanwhile, the Red Sox had gone without October glory since winning the whole ball of wax in 1918. But then all that changed in a span of two years when those teams posted matching clean sweeps of their National League foes in the 2004 (Red Sox over Cardinals) and 2005 (White Sox over Astros) World Series. Now the Cubs are baseball’s lone poster-child for being “long overdue,” “star-crossed,” and all those other adjectives that pundits reserve for seriously hapless losers. The 2003 “Bartman Incident” in the National League Championship Series against the Marlins only perpetuated the notion that the Cubs are plagued by a curse.

Amidst this perpetual disappointment, Cubs fans seem more impatient than they were a decade ago. But they are still a relatively content bunch, considering their lot in life. For now, they are left to harken back to glory days several generations removed from modern times. At least they can take pride in the fact that during the first two decades of the twentieth century, the Cubs fielded the most prolific trio of defensive infielders ever seen. The second baseman was Johnny Evers; the shortstop, Joe Tinker; and the first baseman, Frank Chance. Third-sacker Harry Steinfeldt was no slouch either, leading the league in fielding percentage three times. But “Tinker to Evers to Chance,” became a familiar refrain among Chicago fans, who delighted in watching the boys zip the ball around the infield to complete one double play after another.

Two of the most dramatic home runs in history were struck at Wrigley. Unfortunately for Cubs fans, though, only one was hit by the home team. During Game 3 of the 1932 World Series, the Yankees’ Babe Ruth stepped to the plate in the fifth inning with the score tied 4–4. After yelling something at Cubs pitcher Charlie Root, Ruth pointed his bat toward center field, and on the next pitch smacked a titanic clout into the bleachers, right where he had pointed. The “Called Shot” propelled New York to a four-game sweep.

Kevin:

The big fella was probably swatting away a mosquito and the colorful writers of the day amped it into something it wasn’t.

Josh:

Speak for yourself. I’m a believer. Anyone who can eat thirty-eight hot dogs in a sitting can call homers and maybe even walk on water as far as I’m concerned.

Kevin:

Dude, you just compared Kobayashi to Jesus. Not cool.

Josh:

I thought we were talking about the Bambino.

Kevin:

Lennon did the same thing and it was all downhill for the Beatles afterwards.

Josh:

What the hell are you talking about?

As for the other really famous homer in Wrigley lore, it was struck on the penultimate day of the season in 1938. Cubs player-manager Gabby Hartnett hit the “homer in the gloaming,” to break a 5-5 tie against the Pirates. The walk-off, which put Chicago a game ahead of Pittsburgh in the standings, came with two outs and no one on base in the bottom of the ninth when, because of the encroaching darkness, the umpires had already announced they would rule the game a tie after Hartnett’s at-bat. But it never came to that. As the shot sailed into the early autumn night, the screams of euphoria rang up and down Waveland Avenue. The next day, the Cubs won the pennant.

One of the best-pitched games ever was spun at Wrigley. On May 2, 1917, the Cubs’ “Hippo” Vaughn and the Reds’ Fred Toney posted matching goose-eggs for nine full. That’s zeroes as in no-hits. Then, after Vaughn gave up a clean single to Larry Kopf and saw him score on a bunt single by Olympic hero Jim Thorpe in the top of the tenth, Toney finished his no-no, retiring the Cubs in order.

No less a baseball visionary than the great Bill Veeck is credited with planting the trademark ivy that grows on Wrigley’s brick outfield walls. He patted the vines into the soil in 1937. The man who would go on to own the White Sox, Indians, and St. Louis Browns got his start in the game managing a hot dog stand at Wrigley while his father served as Cubs general manager. The original vines consisted of 350 Japanese bittersweet plants and 200 Boston ivy plants. When the ivy originally sprouted, eight Chinese elms accompanied it, growing out of large pots in the bleachers. But leaves started falling on the field and the trees had to be removed.

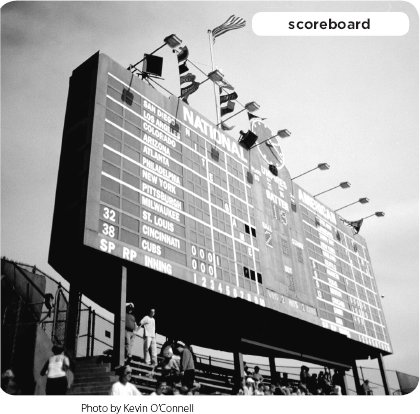

The hand-operated scoreboard also dates to 1937. Due to its historic landmark designation, the board appears almost exactly as it did in the 1970s, offering room for just twelve out-of-town scores. This means that on days when all thirty MLB teams are playing, three scores cannot be posted. In its day, the board must have seemed like a colossus, rising eighty-five feet above the field. It appears drab and small by today’s standards, but charming. Listen for the rhythmic clicking it makes when the numbers change. No one has ever hit the board with a batted ball, though a shot by Roberto Clemente once came close.

What better place to fly a flag than the Windy City? After each game, the Cubs raise a banner bearing either the letter “W” or the letter “L” to let commuters on the “L” know how the home team fared.

Trivia Timeout

Easy Breeze:

Which former Cub once played for teams in all four Major League divisions in a single season?

Blustery Gust:

Name the only two Major Leaguers to play in five different decades.

The Hawk:

In what city was the original Wrigley Field located? (Hint: It began as a minor league park, before serving as home to an expansion team.)

Look for the answers in the text.