Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco (30 page)

Read Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco Online

Authors: Judy Yung

By reaching out to the second generation in this way, Chinatown

churches hoped to fulfill their mission of simultaneously Christianizing

and acculturating this growing group of Chinese Americans. Most Chinese girls participated in church more for social than for religious reasons. Alice Sue Fun, for example, considered attending embroidery

classes at the Chinese Congregational church a social highlight of her

childhood, while many others, like Jade Snow Wong, became Americanized through their participation in Christian organizations such as the

Chinese YWCA. But even as they adopted Western ways and middleclass values, they did not totally forsake the Chinese values and customs

fostered by their families and community. Most continued to maintain

traditional values of respect for the elderly, family harmony and unity,

discipline and excellence in education and work, as well as an appreciation for Chinese opera and art, food, and celebrations. In this way, they

were pragmatic like their mothers, taking what was useful to them from

Western religion and seeing no contradiction in practicing both cultures

at the same time.

In the 192os, second-generation girls were particularly drawn to the

Chinese YWCA because its wide range of services met many of their

needs. It provided them with a quiet place to study; a library collection

for leisure reading; kitchen and bath facilities, which were appreciated

by those from crowded homes; a piano and sewing machine; access to

the swimming pool at the Central YWCA; classes in gymnastics, American cooking, dressmaking, and music; employment and housing assistance; and social interaction in recreational clubs that were organized

and run democratically by the girls themselves. 106

The YWCA also groomed its members for civic duty. Its oratorical

contests, cosponsored with the YMCA, helped women develop public

speaking skills, self-confidence, and political consciousness. One competition, for example, focused on "Our Duty to Serve Chinatown."107

Emma Lum, who won first prize, later became the first Chinese woman

to practice law in California in 19 5 3. The YWCA constantly reminded

Chinese American women to exercise their right to vote, and it also nurtured their participation in fund-raising efforts and major events in the

community. Moreover, the Girl Reserves was often the only avenue by

which some Chinese girls socially interacted with other races outside Chinatown. In these ways, the YWCA helped them broaden their social life,

develop their leadership skills, and become more active in group functions and community affairs.

Christianity, along with Chinese nationalism, also inspired the founding of the Square and Circle Club, the earliest and most enduring service organization of second-generation Chinese women. It all began on

a Sunday afternoon in -1924 when seven young women-Alice Fong,

Daisy L. Wong, Ann Lee, Ivy Lee, Bessie Wong, Daisy K. Wong, and

Jennie Lee-got together as usual after Sunday service at the Chinese

Congregational church to chat, read the Sunday papers, and do the crossword puzzle. That day, an article about flood and famine in the Guangdong area of China caught their attention. This distressful news stirred

them to action. Organized as the Square and Circle Club-in keeping

with the shape of the Chinese coin and a Chinese motto, "In deeds be

square, in knowledge be all-around"-the young women embarked on

their first fund-raising event, a jazz dance benefit to be held outside Chi-

natown.10s The nationalist cause that had spurred their social activism

was no different than that which had first propelled their mothers into

the public arena; but the modern, bicultural style of their first event

clearly reflected their unique identity as American-born Chinese women

with middle-class values.

The local newspaper called attention to this unconventional event,

which marked the debut of a new generation of Chinatown daughters:

"Shake Wicked Hoof in Yankee Hop" Chinese Jazz Dance Tonight:

Square and Circle Club to Give Real American "Hop"

A new blend of the oriental and the occidental in San Francisco! Sixteen little Chinese co-eds are sponsoring an American jazz dance.

To those who know the customs of old China, this undertaking of

the flappers of Chinatown is a remarkable event in the annals of convention smashing....

The dance combines the characteristics of both peoples-American

jazz by Chinese orchestra, and American dancing by Chinese girls in

American party frocks and high heels.

As observed by the reporter, second-generation women were breaking

out of their traditional gender mold in assuming the responsibility for

organizing a major fund-raising event in the same way that other American girls did:

The members of the Square and Circle Club-American-born Chinese girls-have startled Chinatown with their occidental managing of a

dance to be given tonight in Native Sons' Hall at Geary and Mason streets

for the benefit of the Chinese Flood and Famine Relief.

"Usually the Chinese Chamber of Commerce or the Six Companies

are in charge of these charitable and public affairs," Alice Fong, presi dent of the girls' club, said today. `But we wanted to help, too. American girls can do these things. Why shouldn't we? "109

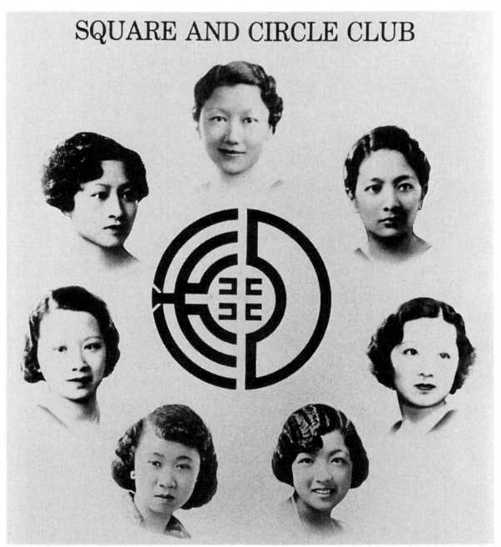

Charter members of the Square and Circle Club, founded in 1924.

Clockwise from top: Alice Fong (Yu), Daisy K. Wong, Ann Lee (Leong),

Jennie Lee, Bessie Wong (Shum), Ivy Lee (Mah), and Daisy L. Wong

(Chinn). (Judy Yung collection)

In the years that followed, the club's membership roll continued to

grow, stabilizing at about eighty members and attracting secondgeneration women looking for a social niche to express their bicultural

identity and civic pride. As was true of other American women's clubs

at this time, members tended to be middle-class women who were well

educated and employed in white-collar or professional work. Likewise,

almost all of the club's activities focused on charity projects that were

extensions of women's domestic role as caregivers.110 Proceeds from

American-style fund-raisers-hope chest raffles, variety shows, musical performances, and fashion shows-were used primarily to support orphans at the Chung Mei Home, Ming Quong Home, and Mei Lun Yuen;

Chinese patients at the Laguna Honda Home and Chinese Hospital; and

youth programs at the Chinese YWCA and YMCA. Like the earlier Chinese Women's Jeleab Association, the Square and Circle Club followed

the American practice of democracy by establishing bylaws that stipulated equal and active participation from its members. Both clubs also

shared the goal of providing mutual aid to their exclusively female members. During the early years, the Square and Circle Club established a

Friendship Fund, whereby grants and loans could be made to young

women for educational, health, and emergency use. Other activities included helping women find jobs, working with the Chinese YWCA to

establish and operate its dormitory, and entering the only women's float

in the Chinese New Year parade in the late 19zos.111

Although none of the Chinese women's organizations addressed feminist issues at this time, the Square and Circle Club did take a number

of strong stands on racial, social, and political issues that affected the

welfare of the community. Club minutes indicate that letters were written to government officials asking for longer hours and better lighting

at Chinese Playground, a dental and health clinic for Chinatown, retention of Chinatown's only Chinese-speaking public health nurse, public housing, and passage of immigration legislation favorable to the Chinese. The club also worked with other community organizations to

register voters, clean up Chinatown, protest racist legislation such as the

Dickstein Nationality Bill and the Texas Anti-Alien Land Bi11,11z and support the anti-Japanese war effort in China.

To this day, although its influence has waned, the Square and Circle

Club continues to function as a women's service organization in San

Francisco. To its credit, countless numbers have benefited from its generosity and from being members in the organization. At a time when

few social channels were open to American-born Chinese women, the

Square and Circle Club provided them with an opportunity to belong,

to socialize with peers, and to exercise their civic duty. In the process,

the women developed self-confidence, leadership skills, a newfound spirit

of teamwork, and took pride in their bicultural heritage and community service. As Ruth Chinn, an active member since 1948, commented

in her 1987 senior thesis on the Square and Circle Club:

The Hope Chest Raffle brought the members together. A night was set

aside for knitting, embroidering, and crocheting to fill the Hope Chest.

The shows and musical extravaganzas were projects that brought to the forefront the many talents of the individual members. They were superstars, whether playing the lead or bit part in a show, singing in the choral

group, dancing in the chorus line, sewing costumes, set designing, making the props, writing the script, or being the "director"-we did it all! ...

Together, not only did we have fun (although frustration, anger, and anxiety went along with it all) producing the shows, we also raised impressive funds to fill our coffers to support our many community service commitments. 113

Like the Chinese YWCA, the Square and Circle Club was established

under the auspices of a Protestant institution, but as the group developed the church ceased to be a binding force among its members. Although acculturation into American life remained a goal, it was not to

be realized at the cost of losing their Chinese heritage. What kept both

organizations viable was the growing population of Chinese American

women, their continued exclusion from mainstream society as well as

the Chinatown establishment, and the organizations' effectiveness in

serving the social needs of women. At the same time that the services

of the Chinese YWCA and Square and Circle Club benefited the Chinatown community, the leadership training that members received encouraged them to participate more actively in the political arena.

A Dual Political Identity

Compared to their mothers, second-generation women

played a relatively active political role. Their birthright, higher educational attainment, and Western orientation all served to heighten their

political consciousness and desire for civic participation. Whereas their

immigrant mothers had only been encouraged to contribute to Chinese

nationalist causes, American-born daughters became involved in both

Chinese and U.S. politics. Even as they sought ways to express their loyalty to America, they did not shirk their responsibilities to their parents'

homeland.

This dual political identity was planted in the psyches of the second

generation at an early age. Their family upbringing, Chinese school training, and community involvement emphasized their duty to China, while

their public school education and social activities instilled in them a strong

desire to be exemplary American citizens. However, their efforts to exercise their birthright were constantly thwarted by racial discrimination. Even their citizenship status had to be protected by constant vigilance.

In 1913 and again in 1923, California legislators introduced bills in

Congress intended to disfranchise citizens of Chinese ancestry. The Cable Act of 1922 stipulated that a female citizen who married an "alien

ineligible to citizenship" would lose her U.S. citizenship. In all three instances, the Chinese American Citizens Alliance fought successfully to

protect the rights of the second generation. 114 Nevertheless, citizenship

status often did not guarantee Chinese Americans equal treatment. The

discrimination they experienced in school, the workplace, in public areas, housing, and marriage made them feel all too keenly their real status as second-class citizens. The following sentiments of two secondgeneration Chinese Americans were all too common:

I speak fluent English, and have the American mind. I feel that I am more

American than Chinese. I am an American citizen by birth, having the

title for all rights, but they treat me as if I were a foreigner. They have

so many restrictions against us. I cannot help it that I was born a Chinese.