Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco (33 page)

Read Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco Online

Authors: Judy Yung

Florence met her husband while studying at the University of Chicago. Upon their marriage in 1923, they decided to go live in China.

Five years later, when they returned to the United States, he, as a student, was permitted to land immediately, but she and her two children

were detained on the boat. "The immigration officer said, `It's because

you're married to an alien and lost your citizenship.' And that was the

first time that I knew that I had lost my citizenship when I married,"

she recalled. Only after a friend who worked for the Immigration Service vouched for her identity was she allowed to land. "[On her word]

I got off without paying the $z,ooo bond for me and $z,ooo for the

children. After that, I said, I'm not coming back here any more."155 But

her husband's work as a physician necessitated trips to the United States

every five years, so finally, in 193 6, she applied for naturalization and regained her U.S. citizenship.

Flora Belle also met her foreign-born husband while a student at the

University of Chicago. They married in 1926, and she decided to return to China with him in 1932. According to a letter she wrote her

friend Ludmelia before departing, she was aware of the impact the Cable Act had on her and zealously tried to adjust her status through naturalization before leaving for China.

Here's the problem. I must have my birth certificate. After that, I must

apply for citizenship since I lost it by marrying an alien according to a recent law. I am permitted to apply for it by paying a $ i o fee and passing

an examination, providing that I have my birth certificate. I must go

through this before I ever dare leave America because once I am out of

the country, as an alien, I'll have a devil of a time trying to get back. And

I know that I will always want to come back because it is my home. 156

Unfortunately, no doctor had presided at Flora's birth; therefore, no

birth certificate was on file in Fresno County, where she was born. But

a U.S. District Court judge in Chicago evidently believed her and allowed her to "repatriate" as a U.S. citizen before she left for China.157

Her foresight in this matter allowed her to escape war conditions in China

and return to the United States in 1949 as a U.S. citizen along with her

two daughters who had been born in China.

Aside from the Cable Act, anti-miscegenation attitudes and laws that prevented interracial marriage between Chinese and whites discriminated against Chinese women as well. Compounding the problem was

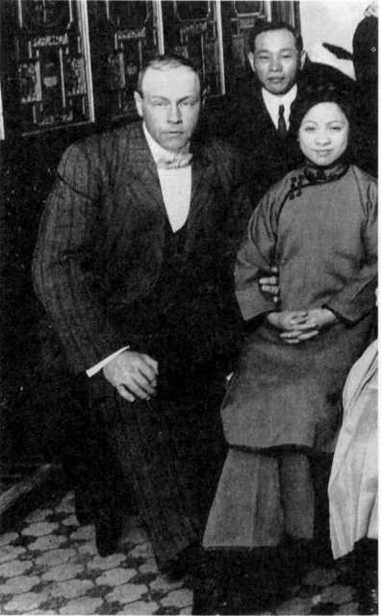

ostracism in the Chinese community with respect to intermarriages. Tye

Leung, who had run away to the Presbyterian Mission Home to avoid

an arranged marriage, found herself the target of such shunning. While

employed as an assistant to the matrons at Angel Island, she met and

fell in love with an immigration inspector, Charles Schulze. They had to

travel to Vancouver, Washington, to become legally married. "His

mother and my folks disapprove very much, but when two people are

in love, they don't think of the future or what [might] happen," she

wrote later in an autobiographical essay. 15s After their marriage both had

to resign from their civil service jobs because of social ostracism. Charles

went on to work for many years for the Southern Pacific Company as a

mechanic, and Tye found a job as a telephone operator at the Chinatown Exchange. Although they were "the talk of Chinatown," according to one of her contemporaries, the Schulzes chose to live close to

Chinatown, and Tye remained active in the Chinese Presbyterian church.

Their children, Fred and Louise, recalled that they were one of the few

interracial families in Chinatown, and although they as children were

sometimes called fangwai jai (literally, foreign devil child), they were

accepted in the community, most likely because their mother spent many

hours volunteering in the community.159 Her son Fred said, "She was

very kind and always willing to help other people go see the doctor, interpret, go to immigration, and things like that. Very often she would

take the streetcar and go out to Children's Hospital to interpret on a

volunteer basis." 160

Discriminatory laws such as the Cable Act and the Anti-Miscegenation Act went hand-in-hand with other anti-Chinese measures and practices that sought to stop Chinese immigration and the integration of Chinese into mainstream America. Such laws were often both racist and sexist

in character and created hardships for Chinese American women already

hampered by cultural conflict at home. They were painful reminders of

the vulnerable existence of the second generation, who, in spite of their

rights as U.S. citizens, could easily become disenfranchised on the basis

of race alone.

Other American laws, however, such as divorce laws, gave Chinese

American women leverage and latitude in changing their marital circumstances. Although few cases of divorce among Chinese Americans

were reported in the local newspapers, Caroline Chew wrote in 1926

that "divorce among Chinese in America has become comparatively com mon, and although it is still looked upon with a little distaste, if it is

quite justifiable, no one has anything disparaging to say." She added that,

unlike in China, wives in America had just as much right as husbands to

sue for divorce. 16I According to local newspapers, one major source of

information on divorce patterns in the Chinese American community,

important causes of divorce among second-generation women included

wife abuse and polygamy. In 1923, for example, Emma Soohoo sued

her American-born husband, Henry, for divorce on grounds that he

"cruelly beat her and then deserted her," and she requested sole custody of their twenty-month-old baby.162 As another example, in 1928

Amy Quan Tong, the owner of a manicuring parlor in Chinatown, filed

for divorce from her American-born husband, Quan Tong, because, as

she told the judge, he had put her to work at low wages in his Hong

Kong candy store and taken a second wife .161

Charles and Tye Leung

Schulze. (Courtesy of

Louise Schulze Lee)

Like second-generation European American women, Chinese American women who married men of their own choice often embarked on

a life quite different from that of their immigrant mothers. To start, they

were not as confined to the domestic sphere, as Caroline Chew points

out:

She is perfectly free to come and go as she pleases and has free access to

the streets. She goes out and does her own marketing; goes calling on

her friends when she so desires; dines at restaurants occasionally; and even

ventures to go beyond the precincts of "Chinatown" quite frequentlyall of which have hitherto never been done by a Chinese woman. Fifteen

or twenty years ago such conduct would have been considered most outrageous and would have caused a woman to be all but ostracized.164

There was also more equality, mutual affection, and companionship in

second-generation marriages. Not only did couples go out together, but

they were not afraid to express their affection in public. Because both

worked and contributed to the family income, they tended to discuss

matters and make joint decisions regarding the family's welfare. Secondgeneration husbands were also less resistant to helping with the housework and sharing their outside concerns with their wives. Daisy Wong

Chinn found her marriage of fifty-two years fulfilling as well as happy

because she and her husband, Thomas W. Chinn, communicated well

and worked together on many community projects. Thomas was always

forward-looking, she noted. He opened the first sporting goods store

in Chinatown in 1929 and founded the Chinese Digest in 193 5. "Whatever projects he has," she said, "he always says, `Well, what do you think

of this?' And I'm his best critic because I always tell him what I really

think; and then he can decide for himself whether my thoughts are better." In most cases, she said, he took her suggestions. 165

Jade Snow Wong shared a similarly close and equal relationship with

her husband, Woody Ong, about whom she wrote in No Chinese

Stranger, the sequel to Fifth Chinese Daughter. Old family friends, the

two became reacquainted after they had both established their businesses

in Chinatown and were thrown together by a family emergency. As Jade

Snow put it, "Each grew in awareness of the other, and devotion flowered." Their married life was wedded to their work life, as they lived and

worked together on the same premises.

In this first year of marriage, they often walked the three blocks to Chinatown for a restaurant lunch, after which they would purchase groceries

for that night's late Chinese dinner at home. The division of their studio work was natural. Financial records and bank deposits, mechanical problems, chemical formulas, checking kiln action, packing, pickup, and

deliveries naturally fell into Woody's hands while Jade Snow stayed close

to home, working on designs, supervising staff schedules, and keeping

house. True to tradition, once Woody had locked the studio door and

come upstairs, he was home as a Chinese husband, expecting their house

to be immaculate and to be waited upon and indulged. They could consult with each other on just about every subject without disagreement.

Kindness, devotion, protection with strength new to her, and extravagant gifts were privileges that gladdened Jade Snow's heart, while her

husband's physical comfort and mental relaxation were her responsibility. 166

Although their marriage revealed a traditional gender division of labor,

neither partner dominated the other. As their family grew to four children and they added an active travel business to their ceramics work,

Woody proved a supportive partner, helping with the children and household chores, encouraging Jade Snow's career in ceramics and writing,

nursing her back to health when she became ill, and sharing responsibilities with her on the many tours to Asia that they cosponsored.

Similarly, Tye Leung's marriage to Charles Schulze, despite being

handicapped by the taboo against interracial marriage, was successful because it was both egalitarian and interdependent. According to their son,

Fred, "We had good family relations. I never heard arguments, fights,

or anything." Both parents were kind and mild-tempered, and both

worked to provide for the family. Tye did most of the cooking and housework, but in the evenings, when she was working at the telephone exchange, Charles would take care of the children and of Tye's mother,

who lived with them. Fred fondly recalled: "Before we went to bed each

night, my father would always bring us a cup of cocoa. Then after he

gave us our cocoa, he would take the dishes out to the kitchen, wash

them, and put them away." 167

Both parents loved music and led an active social life. Tye played the

piano and Chinese butterfly harp and attended the Chinese Presbyterian church regularly; Charles played the French horn with a military

band and was active at Grace Cathedral. Tye would often go to the Chinese opera, weddings, and birthday parties in Chinatown accompanied

by her children, while Charles played with various musical bands in the

city and attended regular meetings of the Odd Fellows Lodge. Although

they led different social lives, they were a close family. They always ate

and played together at home on Sundays, Fred recalled. Not only was

the marriage a happy one, but the children benefited from the cultural

strengths of both parents and the warm family life they provided.

Jade Snow Wong and her

husband, Woodrow Ong,

packing her ceramics, which

accompanied them on her

speaking tour in Asia for the

U.S. State Department, 1953.

(Associated Press photo;

courtesy of Jade Snow Wong)

Further factors that distinguished between traditional and modern

marriages among Chinese Americans included the size of the family and

the quality of home life. Unlike their mothers, second-generation

women knew about and had access to birth control, which became more

available to American women in the 19 zos. "My friends were very good

to me and told me what to do," said Gladys Ng Gin. "When it was time

to have nmy first baby, a good friend of mine said, `Gladys, you have to

go to the hospital,' and she introduced a woman doctor to me." 1611 Most

of her contemporaries-both European and Chinese American-limited their families to two or three children and had them in the hospital. However, some "modern" husbands proved uncooperative. Flora

Belle Jan's health was ruined after five abortions because her husband

refused to practice birth control. She confided to Ludmelia: