Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco (46 page)

Read Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco Online

Authors: Judy Yung

All Chinatown has come to agree that it was the most magnificent, heartwarming and spontaneous spectacle ever given in this go-year community.... Chinatownians had always known the sympathy and generosity

of the American people toward the people of China. But whereas before they had only read or been told of it, on the night of June 17 they

saw it-saw it in the faces of Zoo,ooo Americans as they milled into Chinatown, as they vied on purchasing "Humanity" badges, and as they literally poured money into rice bowls placed everywhere for that purpose.

The cause of this active sympathy was very pithily expressed in four Chinese characters written on a strip of rice paper pasted in front of a store

which read: "America Believes in Righteousness."55

So great was the success of San Francisco's first Rice Bowl party that

the community decided to expand the second one to three days in 1940,

and the third one to four days in 1941. These parties were even more

spectacular, with the addition of fireworks that reproduced historical Chinese and American scenes, floats that blended Chinese history and

mythology, an auction of donated Chinese merchandise-tea, jewelry,

and art goods-that lasted for hours and brought in thousands of dollars, and a new dragon, constructed by Chinese artisans from the International Exposition at Treasure Island. The second Rice Bowl party

brought in $87,000, while the third reaped $93,000.56

The Rice Bowl parties would not have been as successful without the

active participation of women in the origin, planning, and implementation of the event. Where Chinese women particularly stood out was in

their role carrying the Chinese flag in the parades. Measuring seventyfive feet long and forty-five feet wide, the flag weighed over three hundred pounds and required one hundred women to hold it aloft. As the

women marched through the streets, coins and bills were thrown into

the outstretched flag. So heavy did the flag become that each parade had

to be stopped at least three times for the flag to be emptied.57 This scene

of a hundred proud women-young and old, all wearing cheong sum,

China's national dress-was repeated throughout the country every time

there was a parade to raise funds or commemorate the Humiliation Days

when Japan attacked China. Their high visibility as flag carriers in these

parades could be said to symbolize the merging of nationalism with feminism: the move of Chinese American women from the domestic into

the public arena on behalf of the war effort.

Women proudly carrying the Chinese flag through the streets of Chinatown

to raise money for the war effort in China. (Harry Jew photo)

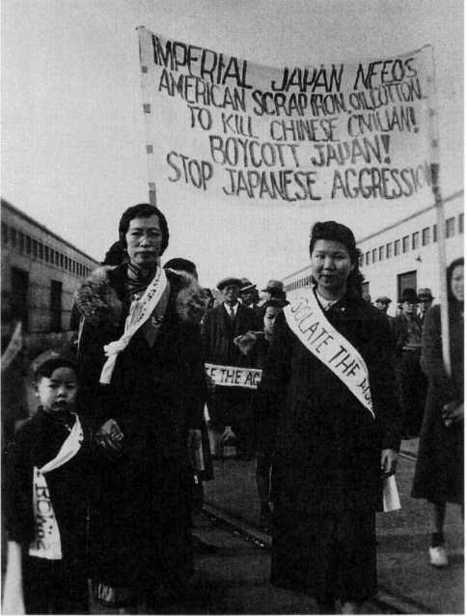

PICKET DUTY

The other dramatic image of Chinese women during the

war years is of picketers protesting the shipping of scrap iron to Japan.

Organized by the Chinese Workers Mutual Aid Association and as reported by Lim P. Lee in the Chinese Digest, a mass protest in San Francisco was set for r r A.M. on December 16, 19 3 8. By word of mouth,

people began gathering for picket duty at io:3o at the corner of Stockton and Clay Streets. By "zero hour," more than two hundred volunteers had arrived; they were transported, singing, shouting, and cheering, to Pier 45, where the S.S. Spyros, a ship owned by Japan's Mitsui

Company, was docked. There they were joined by three hundred sympathetic Greeks, Jews, and other European Americans. As the word

spread, Chinatown restaurants and grocery stores did their part by providing free drinks and food-roast pig, sandwiches, pork buns, oranges to the picketers and longshoremen for the duration of the demonstra-

tion.58

The picket line comprised many different factions, including the political right and left, Christian and secular groups, all classes and ages.

One reporter described the scene thus:

Despite the pouring rain and the muddy roads, both men and women

assembled on time, the most enthusiastic participants coming from the

Chinese YWCA, Chick Char Musical Club, United Protestants Association, Presbyterian Mission Home, and the Kin Kuo Chinese School. Ten

Chinese women who came all the way from Stockton further aroused the

spirit of the occasion. As the men and women marched in a circle in the

pouring rain, the red ink on their signs ran and their faces became wet

with raindrops so that it appeared as if they were splattered with blood

and tears.... Joining the picket line was a number of elderly women,

hobbling on feet once bound. Old men, hunched and bald, marched

alongside the young and strong. The scene was enough to move one

to tears.59

The picketers' cries of "Longshoremen, be with us! Longshoremen,

be with us!" and their picket signs, "Stop U.S. scrap iron to Japan! Prevent murder of Chinese women and children!" succeeded in gaining the

sympathy and support of the longshoremen who were responsible for

loading the S.S. Spyros with scrap metal bound for Japan. In political

solidarity, the majority of the longshoremen refused to cross the picket

line upon their return from lunch break. By the fourth day of the protest,

with Chinese American supporters pouring in from nearby towns, the

picket line had grown to five thousand strong and now included the S.S.

Beckenham, an English freighter docked at the same pier. A vote by the

full membership of the International Longshoremen and Warehousemen's Union (ILWU) resulted in "ioo percent opposed to passing the

picket line," despite threats of a coastwide lockout of all longshoremen

by the Waterfront Employers Association. For five days the Spyros lay

quiet. After negotiations between the ILWU and CWRA, the protest

was finally called off on December zo with the understanding that the

union would organize a coastwide conference to promote an embargo

on all materials to Japan. Not wanting to hurt commercial business

in San Francisco further, and considering their goal of publicizing the

need for an embargo against Japan accomplished, the Chinese picketers

withdrew. They marched past the longshoremen's headquarters to express their appreciation and then through downtown San Francisco

and back to Chinatown, singing China's song of resistance, "Chi Lai

(Arise)" or "March of the Volunteers." True to their word, organized labor, in cooperation with American Friends of China, the Church Federation, and CWRA, spearheaded an embargo petition campaign and organized mass meetings in January and February to launch a national embargo movement. Chinese Americans continued to press for an embargo

until 1941, when Congress finally authorized President Roosevelt to prohibit the sales of arms to Japan.60 In this effort, women played a major

role by assuming picket duty and lobbying Congress.

Lai Yee Guey How with son Art (left) and Nellie Tom

Quock (right) lead the picket line against sending scrap iron

to Japan. (Courtesy of Lorena How)

FUND-RAISING AND RED CROSS WORK

Two areas that were considered the domain of women in

the war effort were direct solicitation of money and Red Cross work.

Because men found asking for donations distasteful, they pushed the task onto women, whom they said people in the community found more difficult to refuse. The CWRA made it a point to organize women's brigades

whenever it sponsored a fund-raising campaign.61 During the CWRA's

second relief campaign in 1937, for example, fifty-four women made up

six of the twelve brigades responsible for canvassing the San Francisco

Bay Area for contributions. By the fifth day of the campaign, CSYPre-

ported that one-quarter of the $6oo,ooo goal had been met, and one

of the women's brigades was praised for bringing in the top amount of

$3,8oo on that day.62 This was no mean feat, considering the depressed

times and the many noteworthy causes that competed for donations in

the community, including victims of natural disasters in China; schools,

hospitals, and orphanages in China; the Community Chest; Chinese Hospital; Chinese schools; churches and community organizations such as

the YWCA, YMCA, and Square and Circle Club; Mei Lun Yuen orphanage; and Chinese deportees from Cuba.63

Throughout the war years, Chinese women from various walks of life

also assumed the traditional female tasks of Red Cross work. Soon after

the 9-18 and i - z 8 incidents, women volunteers gathered at the Chinese

YWCA, Chinese Hospital, Baptist Church, and Presbyterian Mission

Home to prepare bandages and medical supplies for China's battle-

fronts.64 As the war intensified and the community was bombarded with

reports of wounded soldiers and civilians, women increased their volunteer Red Cross activities. During the summer months of 1937, for

example, garment workers in Chinatown made, on their own time, six

thousand flannel jackets of double construction for civilians in the war

zones. In December of that same year, they volunteered to sew ten thousand inner garments for wounded soldiers.65 Many Chinese American

women also put in regular hours preparing supplies for refugee relief at

the Chinese American Citizens Alliance and at the San Francisco branch

of the American Red Cross.66

Among the most active in Red Cross work was none other than Dr.

Margaret Chung. She had volunteered for medical service at the front

lines but had been dissuaded by both the Chinese and American governments. "They felt I could do more good raising funds for medical

supplies here in this country," she told radio audiences. "Today women

and children are suffering in China-dying without even a chance to be

saved. There is a great need for the most elementary sort of medical supplies. And I have made the raising of a medical fund my work for the

present."67 A charismatic figure, Dr. Chung took it upon herself to lecture all over the country on behalf of the war effort in China and to use her social connections in show business to sponsor benefit performances

in local theaters outside Chinatown. One such benefit that featured both

Chinese and American stars raised enough money to send $1,700 worth

of drugs, medical supplies, and vaccines to China via the National

Women's Relief Association in Hong Kong.68 With foresight she worked

with the American Red Cross to establish a Disaster Relief Station in

the basement of Grace Cathedral in the Nob Hill district in 1939. "Some

people do not realize how efficiently and farsightedly the American Red

Cross works, but when the Japanese struck on December 7, 1941, we

worked feverishly and by io:oo that night huge packing cases were loaded

upon the decks of the U.S.S. Mariposa and were sent away out to Pearl

Harbor," she wrote years later. For her "meritorious personal service performed in behalf of the nation, her Armed Services, and suffering humanity in the Second World War," Dr. Chung received a special citation

from the American Red Cross.69

RECEPTIONS FOR WAR HEROES

Women's war work also included hosting receptions for

Chinese dignitaries and war heroes when they came through San Francisco. Particularly notable were the large welcoming receptions that Chinese women hosted for female role models such as the war hero Yang

Hueimei, the aviator Lee Ya Ching, Madame Chiang Kai-shek, and

United Nations delegate Wu Yifang. Here were four Chinese women held

in high regard by their countrymen and countrywomen for contributions that broke with traditional gender roles. Meeting and hearing them

speak on the role of women in the war not only boosted nationalist fervor but also inspired feminist pride among Chinese American women.

Yang Hueimei, famous for carrying the Chinese flag and supplies

across enemy lines during a decisive battle in Shanghai, was given a hero's

welcome when she came to San Francisco in 1938, after attending the

Second International Youth and Peace Conference in New York. CSYP

reported that among the seventy-eight carloads of people who greeted

her at the pier were representatives from five women's groups, part of

CWRA's welcoming committee.70 "She was adored by all the inhabitants of Chinatown," recalled Jane Kwong Lee. "And when she made

an appearance at the Chinese YWCA auditorium, the hall was jammed."71

Her speech was inspiring:

I thank you for the title of "hero," but I am a mere citizen. In this time

of national crisis, I am but fulfilling my duty. The loss of Canton recently has caused overseas Chinese much pain and grief, but we must not despair.... The enemy's airplanes are indeed powerful, but our blood and

flesh are even more powerful. We must use our blood and flesh to wash

away our country's humiliation and build a new China. Your contributions as overseas Chinese are important.... We must unite and fight to

the end, for the final victory will be ours.72