Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco (49 page)

Read Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco Online

Authors: Judy Yung

Maggie Gee, one of two Chinese American women who volunteered

with the Women's Airforce Service Pilots Program (WASP) transporting military aircraft around the country, was very aware of sexism in the

service. She had dropped out of college to work at the Mare Island Naval

Shipyard in north San Francisco Bay, drawing plans for the repair of destroyers and submarines. "What we were doing in the shipyard was important," she said, "but we wanted to do something more, something

more exciting.""' Inspired by Amelia Earhart and the romance of flying, she and two other friends left Mare Island to enroll in flight school.

They later joined the WASP when the age requirement was lowered to

eighteen. Of 25,000 women who applied, only z,ooo were accepted,

and 1,074 graduated and received their wings. "Our flight training was

the same as the men pilots. In primary training, we flew the open cockpit Stearman, which you might see today in airshows doing aerobatics,"

she explained. "In basic training, we flew the 45o-horsepower canopied

BT-113. And in advance training we flew the 65o-horsepower AT-6,

which had radio and retractable landing gear-the kind of plane used

in combat in China."112 By the fall of 1944, half of the ferrying division's fighter pilots were women, and three-fourths of all domestic deliveries were done by Wasps. They also flight-tested damaged airplanes

and flew B-I7s. Thirty-eight woman pilots died because of mechanical

failures, including the only other Chinese American woman, Hazel Ying

Lee of Portland, Oregon. Yet they were known for flying longer hours

and having fewer accidents than their fellow male pilots. Despite their

track record, however, the civilian group of female pilots was forced to

disband a few months before the end of the war because of lobbying on

the part of the male pilots.113 "Even though our numbers were small

and the war was not over, we were sent home," said Maggie. "It was difficult for men to admit that women could fly as well as or better than

men. "114 To add insult to injury, Congress chose not to classify the WASP

as military. While other servicewomen were granted full veteran status

in 11948, Wasps did not receive the same recognition until 1977. Nor

could they find jobs as test pilots with aircraft companies or airlines after the war because of sex discrimination. Still, for Maggie the experience opened up new vistas, transforming her into a more outgoing and

politically aware person. "I returned to Berkeley, California, with a lot

more self-confidence," she said. "My horizon had broadened by the

friendships I made with active women-doers from all parts of the coun-

try."115 Maggie, who never married, went on to become a physicist and

political activist.

Overall, Chinese American women who enlisted in the military found the experience rewarding. Besides giving them the satisfaction of serving their country, it gave them a wider perspective, gained them new

friends, made them more independent and self-confident, allowed them

to travel, and opened up new educational and employment opportunities. "I wouldn't have done half the things I did if I hadn't been in the

service," said Helen Pon Onyett. "Not only did it give me retirement

benefits, but I had a chance to go to school on the G.I. bill and to improve my standing.""' Jessie Lee Yip, who later became a court recorder,

also profited from the G.I. bill, which financed her education in stenography after the war. "It also helped me to grow up, get along with people, and it allowed me to travel," she added. I" Similarly, because of her

two years of service in the WAC, May Lew Gee of San Francisco had a

chance to attend secretarial training school after the war. Her military

experiences also spurred her to become an active member of the Cathay

Post in San Francisco and the American Legion Post in Pacifica, California, as well as to run for public office. May was on the Pacifica Planning Commission for twelve years and has been on the Water Board there

for seventeen years. 118

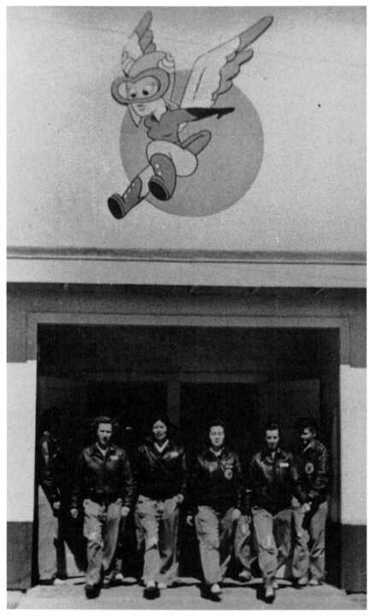

Maggie Gee (second from left) and fellow members of the Women's Airforce

Service Pilots Program. (Courtesy of Maggie Gee)

Marietta Chong Eng of Hawaii, who was motivated to join the

WAVES because her brother was in the navy, found her one year of service as an occupational therapist at Mare Island more positive than negative:

In reflection, my one year of service as a WAVES ensign was like no other

single year of my life. Wearing the uniform made me feel different. On

the streets of San Francisco or at the navy base, I attracted much attention and maybe admiration. On the negative side, I was in uniform in

New York City crossing a busy street when a young hoodlum pointed at

me in surprise and said, "Look, a Chinaman." I guess it was startling to

see a Chinese in uniform. All in all, though, my navy experience was a

good one.

So proud was she of the uniform that she wore it at her wedding: "I felt

that I could not find a more distinctive wedding outfit than this one,"

she said. 119 Marietta settled in Oakland, where she raised three children

and worked for many years as an occupational therapist with the mentally ill.

Ruth Chan Jang, who left a well-paying job with the State of California to join the Women's Air Corps in 1944, said it was a turning point

in her life. Growing up in Locke, California, she had experienced racial

discrimination and been made to feel ashamed of her Chinese background. The service changed all that. As the only Chinese in her unit, she was treated very well, Ruth emphasized. "I was accepted as one of

them. They never made me feel like you have to hang back and be subservient." While in the service she was captain of the basketball team,

given her first surprise birthday party, and promoted to corporal at the

suggestion of the nurses under whom she worked as a secretary. After

the war, Ruth also took advantage of the G.I. bill and went back to college, eventually becoming a teacher. There can be no better testament

of her positive experience in the service and the patriotism it nurtured

in her than her sincere wish that she and her husband, who also served

in the air force during World War II, will "someday, somehow" be buried

at Arlington National Cemetery.'2°

IN THE LABOR FORCE

The draft and the rapid growth of the war industry resulted in a labor shortage that in turn opened up significant job opportunities for racial minorities and women. With the men away at war and

President Roosevelt's executive order against discriminatory hiring practices in place, their labor became crucial in guaranteeing the output of

war materials and food. Black, Mexican, Chinese, and Native American

workers migrated in large numbers to urban centers and city ports to fill

jobs in the defense industries. At the same time, many women found

work in the manufacturing and clerical sectors, while others were able

to enter business and professional fields previously closed to them.

Wartime propaganda played on the themes of patriotism and glamor to

recruit married women into the labor force. Women were encouraged

to emulate Rosie the Riveter-a muscular but pert, rosy-cheeked young

woman, rivet gun slung across her lap and a powder puff and mirror

peeking out of her coverall pocket-to take a war job and so stand behind the man with the gun. During the war years the female labor force

increased by more than 5o percent overall, and by 140 percent in manufacturing and 46o percent in the major war industries. Married women

exceeded single women in the work force for the first time in U.S. history, and woman workers were at last able to gain access to higher pay,

union representation, and such traditionally male jobs as mechanic, engineer, lumberjack, bus driver, and police dispatcher.'2'

The employment of black women increased by more than one-third

during the war years, but racism and sexism combined to hinder their

wartime gains relative to those of white women and black men. On the

positive side, black women were able to move from farm and domestic labor into better-paying jobs in hotels, restaurants, and defense factories. On the negative side, however, black workers of both sexes were

often subjected to discrimination in hiring, training, job assignment,

wages, and promotion.122 Fanny Christina Hill, who spent forty years

as an aircraft worker after getting her start during World War II, put it

like this: "We always say that Lincoln took the bale off of the Negroes.

I think there is a statue up there in Washington, D.C., where he's lifting something off the Negro. Well, my sister always said that Hitler was

the one that got us out of the white folks' kitchen." As Fanny found

out, though, it was an uphill battle:

Corporal Ruth Chan. (Courtesy of Ruth Chan Jang)

They fought hand, tooth, and nail to get in there. And the first five or

six Negroes who went in there, they were well educated, but they started

them off as janitors. After they once got their foot in the door and was

there for three months-you work for three months before they say you're

hired-then they had to start fighting all over again to get off of that

broom and get something decent. And some of them did.123

Overall, despite the new employment opportunities and higher wages for women during the war years, gender inequality persisted in terms of

pay differences and job mobility, not to mention household and child

care responsibilities. After the war, a Women's Bureau poll showed that

74 percent of women workers wanted to remain in the labor force and

86 percent wanted to retain their current jobs; however, public opinion

prevailed: women, it was generally believed, belonged in the home. As

the men returned from the war front, women were laid off at a rate 75

percent higher than that for men, and the occupational structure returned

to its prewar status.'24

World War II proved to be a job boom for Chinese Americans, who

for the first time found well-paying jobs in factories-building ships, aircraft, and war vehicles and producing ammunition-as well as in private

industries. Nationwide, Chinese American men made substantial gains

in the professional/technical and craft fields, while the women, whose

labor force participation almost tripled between 194o and 1950, made

inroads in the clerical/sales, professional/technical, and proprietor/managerial classifications. The image and roles of Chinese American women

on the home front changed dramatically as government propaganda declared them patriotic daughters who were doing their part for the war

effort:

Daughters of women, who, in the Chinese homeland, lived out their

whole lives in the cloistered seclusion of the enclosed courtyard of the

traditional Chinese home, are today not only seeking careers in their

adopted country but are banded together as volunteers to help win the

war.... In aircraft plants, training camps, and hospital wards, at filter

boards and bond booths, in shipyards, canteens, and Red Cross classes,

these girls ... these Chinese daughters of Uncle Sam ... are doing their

utmost to blend their new-world education and their old-world talents

to hasten the end of the war. 121

As far as Lucy Lee of Houston, Texas, was concerned, World War II

was the most important event in her lifetime in terms of job opportunities. A member of one of the first Chinese families in Houston, she

recalled, "We really were a minority. We were not white; we were not

black. Jobs were not open to us at all." Classmates and children in the

neighborhood constantly called them names. "I couldn't tell you how

many [fist]fights I got into trying to protect my brothers and sisters."

Then came the war. "It changed life around. People started to look at

you a little differently and you could get jobs. With no men around, we

had all kinds of opportunities." 126

Census statistics provide strong evidence that the Chinese in San Fran cisco not only made major economic gains during the war but also were

able to hold on to those gains afterward. Between 194o and 195o, the

numbers of Chinese men in domestic service declined, while they increased in the crafts as well as in the professional, technical, and managerial categories. Chinese women fared even better, moving from their

prewar predominantly operative status to jobs in the clerical and sales

fields. Compared to the prewar years, although the labor market was still

stratified by race and gender, Chinese Americans were able to make some

inroads thanks to the war. In 1940, white men dominated the primary

sector (professional, managerial, clerical, and craft occupations), followed

by white women; Chinese men and women, however, were concentrated

in the secondary sector (operative, service, and manual labor jobs). In

1950, although white men and women still dominated the primary sector, they were joined by a significant number of both Chinese men and

women. Whereas in 1940, 36.3 percent of Chinese male workers and

30.8 percent of Chinese female workers were in the primary labor market, by 1950, those figures had climbed to 49.8 and 59 percent, respectively. In contrast, 75 percent of black male workers and 8z percent

of black female workers remained in the secondary labor market after

the war (see appendix tables i i and 12.).