Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco (50 page)

Read Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco Online

Authors: Judy Yung

War production revitalized the San Francisco Bay Area, which developed into the largest shipbuilding center in the world during World

War II. Because of the labor shortage as well as federal guidelines against

discrimination, all six major shipyards in the Bay Area were willing to

hire racial minorities and women to build the cargo ships and tankers

needed for America to win the war.127 With the government sponsoring free classes in marine sheetmetal, pipefitting, electricity, shipfitting,

and drafting, the shipyards carried a labor recruitment campaign to San

Francisco and Oakland Chinatowns.128 According to the Chinese Press,

in 1942. some i,6oo Chinese Americans, out of a total population of

i 8,ooo, were in defense work, primarily the shipbuilding trades; and in

1943, Chinese workers constituted 15 percent of the shipyard work force

in the San Francisco Bay Area.129 In contrast, some 15,000 blacks worked

in the Bay Area shipyards in 1943; at its peak period of production, the

Kaiser shipyard alone employed 25,000 blacks.'3°

The largest shipyard in the Bay Area, the Henry J. Kaiser shipyard in

Richmond, boasted that it employed zo,ooo women out of a total work

force of 90,000, as well as a number of efficient all-Chinese male work

crews that were always ahead of schedule. "I will stack them up against

any other crew in the yard," remarked one superintendent to a newspa per reporter. The point was often made that Chinese shipyard workers

were motivated by more than just American patriotism. "The Chinese

are intent upon building ships as quickly as they can," another reporter

wrote; she then quoted a Chinese worker: "We're doing our part for the

United States [and] our efforts aid China. This is the chance we've been

seeking." Even Chinese women were leaving their homes to work in the

shipyards, "to show their spirit since women in China are to do their

share."131 The Kaiser shipyard's in-house publication, Fore 'n Aft, often

singled out Chinese employees as model workers doubly driven by the

desire to help both China and the United States win the war. In a sexist way, the publication commented on how even "pretty" and "delicate" women like Jane Jeong and Leong Bo San were proving to be

"amazing" workers:

Pretty Jane Jeong had an ambition to fly for China, but when the United

States entered the war, she decided she could better beat the Japs by building ships instead. So Jane's a burner trainee at Yard Two. Two hundred

flying hours are not the fighting lady's only accomplishment, for she's

been a dancer and manager of night club and vaudeville performers. Jane's

husband is a merchant seaman and has not been home once in the four

months of their marriage."'

"Shanghai Lil" is the name they know her by, over at Assembly 1 i on

graveyard shift.... Her name is Leong Bo San. Born in Shanghai, she

was the daughter of a silk merchant. She is five feet, one inch tall, and

she weighs lot pounds.... She has six children. One son is an Air Corps

meteorologist, another is an attorney. Tiny and delicate as she looks, she

works with an energy that amazes people twice her size. Says her boss,

James G. Zack: "I wish I had a whole crew of people like her."133

Marinship in Sausalito also boasted of large numbers of women and

racial minorities in its work force of zo,ooo in 1943 , 300 of whom were

Chinese. In a special issue of its publication Marin-er on "The New

China," Marinship expressed its pride in its Chinese American workers:

"They are practical, teachable, and wonderfully gifted with common

sense; they are excellent artisans, reliable workmen, and of a good faith

that every one acknowledges and admires in their commercial deal-

ings."134 In the same issue, Jade Snow Wong, who was working as a clerktypist at Marinship, wrote that Chinese workers came from all walks of

life and worked in all areas-as janitors, cooks, burners, draftsmen, time

keepers, boilermakers, and secretaries. "They are giving their all to the

job because they know from their Chinese countrymen what Japanese warfare is all about," she said. "Chinese at Marinship are each in his or

her own way working out their answer to Japanese aggression: by producing ships which will mean their home land's liberation." 135

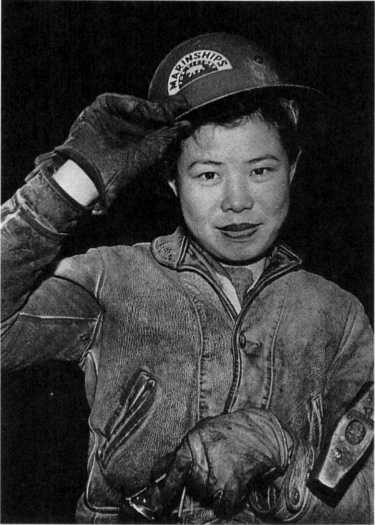

Shipyard worker Lonnie

Young. (Judy Yung collection)

Kenneth Bechtel, president of Marinship, said much the same thing

in a letter he wrote to Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, praising the Chinese workers' patriotic drive and crucial contributions to war production:

The men and women of Marinship, together with all United Nations patriots, pay tribute to the people of China. For more than five years they

have successfully withstood the maraudings of the evil foe, until now our

common road to Victory lies clearly in sight. No small part of the credit

for past accomplishment and future hope belongs to the brave and sturdy

Chinese-Americans who work and fight in the United States. More than

3 00 such patriots, both men and women, are working every day at Marinship, building cargo ships and tankers. We have learned that these Chinese-Americans are among the finest workmen. They are skillful, reliableand inspired with a double allegiance. They know that every blow they

strike in building these ships is a blow of freedom for the land of their

fathers as well as for the land of their homes.136

Indeed, when Marinship became the first shipyard to launch a liberty

ship in honor of a Chinese statesman-the S.S. Sun Yat-sen-Chinese

American employees voluntarily pledged one day's pay to the relief of

Chinese war orphans.137

As Jade Snow Wong pointed out, a mixture of first- and secondgeneration Chinese Americans from all walks of life found work at the

shipyards. Depending on their educational background, Chinese male

workers were assigned jobs in all departments except administration, from

assembly line to construction line to maintenance and services. As for

the women, older immigrants worked in janitorial services, younger

women were trained as draftswomen, burners, and flangers, while high

school graduates and college students were hired as office workers. Despite the obvious absence of Chinese in the top positions, these jobs provided Chinese Americans with union wages and benefits, training and

work experience outside of Chinatown, and the opportunity to contribute to the Allied war effort.

Although yard newspapers claimed that Chinese workers were well

liked and well treated, there were reports of racial and sex discrimination at all the shipyards. Despite liberal hiring policies, blacks were denied membership in parent unions and disadvantaged by restrictive,

union-enforced limitations on their employment and promotions. The

last to be hired and the first to be laid off, they were kept in low-paying

unskilled positions and rarely promoted to positions of authority.138

Women, who in 1943 made up zo percent of the shipyard labor force

in the Bay Area, met with male resistance and were held back in almost

all job categories. Black women, facing both racial and sex discrimination, were generally confined to laboring and housekeeping types of jobs

and were underrepresented in the crafts.139 According to Katherine

Archibald, who worked at Moore Dry Dock in Oakland, whites and Native Americans topped the racial hierarchy in the shipyards, Okies, Jews,

and Chinese were in the middle, and Portuguese and blacks were stuck

at the bottom. "The Chinese," she wrote, "were accepted without resistance or dislike, though with little positive friendliness." 110 It was

known that Chinese at Moore Dry Dock and Kaiser often worked in

segregated crews because of the racist sentiments of fellow employees.

"It's easier to adjust working conditions than try to adjust the prejudice,"

a San Francisco Chronicle reporter stated. A Chinese shipyard worker

interviewed by this journalist complained about being called a "Chink"

by his supervisor and about the lack of promotional opportunities for

Chinese Americans. "I don't think a Chinese boy has a Chinaman's chance," he said. "I have been here many months. Do you think I can

become a leaderman?"141 Although shipyard workers were earning the

highest wages of any industry and women were generally receiving equal

pay for equal work, Chinese workers were held back in almost all job

categories and locked out of certain crafts. Few were ever promoted to

supervisory positions.

Nevertheless, most Chinese American women recalled their shipyard

experience as only positive. Frances Jong, who accompanied her four

brothers to the Mare Island yard, was hired as a shipfitter's assistant. She

said, "It wasn't difficult work. I just carried these angle bars, followed

this Chinese shipfitter around, and did what he told me to do. I learned

a new trade and got good pay for it."142 The only Chinese woman in

her unit, she did not remember any discrimination. Similarly, Maggie

Gee, who was the only Chinese American and one of only three women

in the drafting department at Mare Island, experienced no discrimination, nor did her mother, An Yoke Gee, who worked as a burner. "It

was a positive experience for her," said Maggie. "She made non-Chinese

friends for the first time, and it broadened her outlook in life. She was

satisfied with being part of a Chinese community where she lived, but

this allowed her to become part of the whole."143 Working in the shipyard also introduced Maggie to new friends, a new line of work, and a

new sense of political consciousness. In 1943 she left the shipyard with

two female co-workers she had befriended to join the WASP.

For May Lew Gee, who worked as a tacker at the Kaiser shipyard, "it

was the patriotic thing to do, to work in some kind of war industry." It

was also "great money" and a way to acquire new skills. Whereas before

she had earned only z5 cents an hour waitressing, in the shipyard she

earned $ i. z 6 an hour on the graveyard shift tacking pieces of metal onto

the bottoms of ship bulkheads for the welder to weld together. "Every

couple of days, there's a new ship and you start all over again," she said.

"They were building them faster than you can ever count." Although

she did "the same thing over and over again," she did not consider the

job boring, hard, or dangerous. "We heard about accidents, about people falling off the ship and drowning, but I never saw any or paid any

attention. We just kept working," she said. Nor did she remember any

instances of discrimination. "There was a terrific mixture [of people]

and everyone got along well. They were there to do a certain job ...

build ships so they can go and fight the war." After two years as a tacker,

May left to accompany a pregnant friend back to Detroit, Michigan. Unable to find transportation home, she ended up enlisting in the WAC.144

For someone like Rena Jung Chung, who has always enjoyed "fiddling with machines," working as a burner at the Kaiser shipyard was

the chance of a lifetime. When war broke out, she was the only woman

mechanic at a shop that made spray guns. Her boss closed the shop and

told everyone to go work at the shipyards. Although she was a trained

machinist, Rena started out as a machinist's helper in prefab, where the

front and back parts of ships were built. "All I had to do was to go get

the tools for the machinist and then just stand there doing nothing for

the rest of the day," she recalled. "So I got restless and told the foreman I wanted to do the burning job that looked more interesting to

me." Ruth learned in four hours what most others took forty hours to

master and was able to change her job to burner. Except for the "Okies

[who] asked you all kinds of crazy questions [because] they have never

seen a Chinese [before]," she got along with everyone "because I spoke

good English and I didn't let them pick on me." In addition to receiving good pay, she got to indulge her machinist passions as well as contribute to the war effort.145

Jade Snow Wong wrote in her autobiography that the job of clerktypist at Marinship during the war helped her develop confidence in dealing with male co-workers. Contrary to the opinion of her college placement officer, who had told her that being Chinese would only be a

handicap in the work world, she found that she was accorded nothing

but respect at the shipyard. While there she won first prize in a national

essay-writing contest on the topic of absenteeism. As a reward she was

given the honor of launching the S.S. William A. Jones, which gained

her recognition both at the shipyard and in the Chinese community. At

the launching ceremonies, she said it was her Chinese and American education that helped her find a practical solution to absenteeism in the

war industry; this same Chinese and American unity, she stated, would

help bring the war to an early end.146

Because of the war economy and labor shortage, jobs also opened up

for women in the private sector. White women moved en masse into factory and white-collar jobs, while black women increasingly left private

household service to enter commercial and factory occupations. During

the war, clerical wages increased by 15 to 3 o percent, and factory wages

grew by 47 percent, although women still earned less than men for the

same type of work.141 Chinese women also made inroads into the private sector, including the Chinatown business world. With the men away

at war or taking on defense work, women were needed to fill Chinatown

jobs. Restaurants broke with tradition and advertised for waitresses, and Chinatown finally saw one of its curio shops under the management of

a second-generation Chinese American woman.148 Overall, Chinatown

restaurants experienced a 300 percent increase in business between 194 r

and 1943, while bars and nightclubs did a brisk trade serving soldiers

and a fully employed wartime population.149 As Gladys Ng Gin, who

was working as a cocktail waitress at the Forbidden City, exclaimed, "During the Second World War, it was good money-fifty to sixty dollars a

night in tips alone-wow!"150