Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience and Redemption (5 page)

Read Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience and Redemption Online

Authors: Laura Hillenbrand

Tags: #Autobiography.Historical Figures, #History, #Biography, #Non-Fiction, #War, #Adult

On June 13, Louie made quick work of another Olympic 5,000 qualifier, but the toe injured in training opened up again. He was too lame to train for his final qualifying race, and it cost him. Bright beat Louie by four yards, but Louie wasn’t disgraced, clocking the third-fastest 5,000 run in America since 1931. He was invited to the final of the Olympic trials.

——

On the night of July 3, 1936, the residents of Torrance gathered to see Louie off to New York. They presented him with a wal et bulging with traveling money, a train ticket, new clothes, a shaving kit, and a suitcase emblazoned with the words TORRANCE TORNADO. Fearing that the suitcase made him look brash, Louie carried it out of view and covered the nickname with adhesive tape, then boarded his train. According to his diary, he spent the journey introducing himself to every pretty girl he saw, including a total of five between Chicago and Ohio.

When the train doors slid open in New York, Louie felt as if he were walking into an inferno. It was the hottest summer on record in America, and New York was one of the hardest-hit cities. In 1936, air-conditioning was a rarity, found only in a few theaters and department stores, so escape was nearly impossible. That week, which included the hottest three-day period in the nation’s history, the heat would kil three thousand Americans. In Manhattan, where it would reach 106 degrees, forty people would die.

Louie and Norman Bright split the cost of a room at the Lincoln Hotel. Like al of the athletes, in spite of the heat, they had to train. Sweating profusely day and night, training in the sun, unable to sleep in stifling hotel rooms and YMCAs, lacking any appetite, virtual y every athlete lost a huge amount of weight. By one estimate, no athlete dropped less than ten pounds. One was so desperate for relief that he moved into an air-conditioned theater, buying tickets to movies and sleeping through every showing. Louie was as miserable as everyone else. Chronical y dehydrated, he drank as much as he could; after an 880-meter run in 106-degree heat, he downed eight orangeades and a quart of beer. Each night, taking advantage of the cooler air, he walked six miles. His weight fel precipitously.

The prerace newspaper coverage riled him. Don Lash was considered unbeatable, having just taken the NCAA 5,000-meter title for the third time, set a world record at two miles and an American record at 10,000 meters, and repeatedly thumped Bright, once by 150 yards. Bright was pegged for second, a series of other athletes for third through fifth. Louie wasn’t mentioned. Like everyone else, Louie was daunted by Lash, but the first three runners would go to Berlin, and he believed he could be among them. “If I have any strength left from the heat,” he wrote to Pete, “I’l beat Bright and give Lash the scare of his life.”

On the night before the race, Louie lay sleepless in his sweltering hotel room. He was thinking about al the people who would be disappointed if he failed.

The next morning, Louie and Bright left the hotel together. The trials were to be held at a new stadium on Randal ’s Island, in the confluence of the East and Harlem rivers. It was a hair short of 90 in the city, but when they got off the ferry, they found the stadium much hotter, probably far over 100 degrees. Al over the track, athletes were keeling over and being carted off to hospitals. Louie sat waiting for his race, baking under a scalding sun that, he said,

“made a wreck of me.”

At last, they were told to line up. The gun cracked, the men rushed forward, and the race was on. Lash bounded to the lead, with Bright in close pursuit.

Louie dropped back, and the field settled in for the grind.

On the other side of the continent, a throng of Torrancers crouched around the radio in the Zamperinis’ house. They were in agonies. The start time for Louie’s race had passed, but the NBC radio announcer was lingering on the swimming trials. Pete was so frustrated that he considered putting his foot through the radio. At last, the announcer listed the positions of the 5,000-meter runners, but didn’t mention Louie. Unable to bear the tension, Louise fled to the kitchen, out of earshot.

The runners pushed through laps seven, eight, nine. Lash and Bright led the field. Louie hovered in the middle of the pack, waiting to make his move.

The heat was suffocating. One runner dropped, and the others had no choice but to hurdle him. Then another went down, and they jumped him, too. Louie could feel his feet cooking; the spikes on his shoes were conducting heat up from the track. Norman Bright’s feet were burning particularly badly. In terrible pain, he took a staggering step off the track, twisted his ankle, then lurched back on. The stumble seemed to finish him. He lost touch with Lash. When Louie and the rest of the pack came up to him, he had no resistance to offer. Stil he ran on.

As the runners entered the final lap, Lash gave himself a breather, dropping just behind his Indiana teammate, Tom Deckard. Wel behind him, Louie was ready to move. Angling into the backstretch, he accelerated. Lash’s back drew closer, and then it was just a yard or two ahead. Looking at the bobbing head of the mighty Don Lash, Louie felt intimidated. For several strides, he hesitated. Then he saw the last curve ahead, and the sight slapped him awake. He opened up as fast as he could go.

Banking around the turn, Louie drew alongside Lash just as Lash shifted right to pass Deckard. Louie was carried three-wide, losing precious ground.

Leaving Deckard behind, Louie and Lash ran side by side into the homestretch. With one hundred yards to go, Louie held a slight lead. Lash, fighting furiously, stuck with him. Neither man had any more speed to give. Louie could see that he was maybe a hand’s width ahead, and he wouldn’t let it go.

With heads thrown back, legs pumping out of sync, Louie and Lash drove for the tape. With just a few yards remaining, Lash began inching up, drawing even. The two runners, legs rubbery with exhaustion, flung themselves past the judges in a finish so close, Louie later said, “you couldn’t put a hair between us.”

The announcer’s voice echoed across the living room in Torrance. Zamperini, he said, had won.

Standing in the kitchen, Louise heard the crowd in the next room suddenly shout. Outside, car horns honked, the front door swung open, and neighbors gushed into the house. As a crush of hysterical Torrancers celebrated around her, Louise wept happy tears. Anthony popped the cork on a bottle of wine and began fil ing glasses and singing out toasts, smiling, said one reveler, like a “jackass eating cactus.” A moment later, Louie’s voice came over the

airwaves, cal ing a greeting to Torrance.

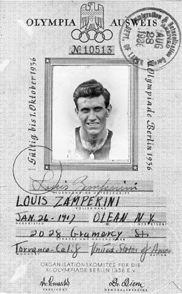

Louie and Lash at the finish line at the 1936 Olympic trials. Courtesy of Louis Zamperini

But the announcer was mistaken. The judges ruled that it was Lash, not Zamperini, who had won. Deckard had hung on for third. The announcer soon corrected himself, but it hardly dimmed the celebration in Torrance. The hometown boy had made the Olympic team.

A few minutes after the race, Louie stood under a cold shower. He could feel the sting of the burns on his feet, fol owing the patterns of his cleats. After drying off, he weighed himself. He had sweated off three pounds. He looked in a mirror and saw a ghostly image looking back at him.

Across the room, Norman Bright was slumped on a bench with one ankle propped over the other knee, staring at his foot. It, like the other one, was burned so badly that the skin had detached from the sole. He had finished fifth, two places short of the Olympic team.*

By the day’s end, Louie had received some 125 telegrams. TORRANCE HAS GONE NUTS, read one. VILLAGE HAS GONE SCREWEY, read another. There was even one from the Torrance Police Department, which must have been relieved that someone else was chasing Louie.

That night, Louie pored over the evening papers, which showed photos of the finish of his race. In some, he seemed to be tied with Lash; in others, he seemed to be in front. On the track, he’d felt sure that he had won. The first three would go to the Olympics, but Louie felt cheated nonetheless.

As Louie studied the papers, the judges were reviewing photographs and a film of the 5,000. Later, Louie sent home a telegram with the news: JUDGES

CALLED IT A TIE. LEAVE NOON WEDNESDAY FOR BERLIN. WILL RUN HARDER IN BERLIN.

When Sylvia returned from work the next day, the house was packed with wel -wishers and newsmen. Louie’s twelve-year-old sister, Virginia, clutched one of Louie’s trophies and told reporters of her plans to be the next great Zamperini runner. Anthony headed off to the Kiwanis club, where he and Louie’s Boy Scout master would drink toasts to Louie until four in the morning. Pete walked around town to back slaps and congratulations. “Am I ever happy,” he wrote to Louie. “I have to go around with my shirt open so that I have enough room for my chest.”

Louie Zamperini was on his way to Germany to compete in the Olympics in an event that he had only contested four times. He was the youngest distance runner to ever make the team.

* Louie’s time was cal ed a “world interscholastic” record, but this was a misnomer. There were no official world high school records. Later sources would list the time as 4:21.2, but al sources from 1934 list it as 4:21.3. Because different organizations had different standards for record verification, there is some confusion about whose record Louie broke, but according to newspapers at the time, the previous recordholder was Ed Shields, who ran 4:23.6 in 1916. In 1925, Chesley Unruh was timed in 4:20.5, but this wasn’t official y verified. Cunningham was also credited with the record, but his time, 4:24.7 run in 1930, was far slower than those of Unruh and Shields. Louie’s mark stood until Bob Seaman broke it in 1953.

* Apparently because of his burns, Cunningham didn’t start high school until he was eighteen.

* Bright wouldn’t have another shot at the Olympics, but he would run for the rest of his life, setting masters records in his old age. Eventual y he went blind, but he kept right on running, holding the end of a rope while a guide held the other. “The only problem was that most guides couldn’t run as fast as my brother, even when he was in his late seventies,” wrote his sister Georgie Bright Kunkel. “In his eighties his grandnephews would walk with him around his care center as he timed the walk on his stopwatch.”

Four

Plundering Germany

THE LUXURY STEAMER MANHATTAN, BEARING THE 1936 U.S. Olympic team to Germany, was barely past the Statue of Liberty before Louie began stealing things. In his defense, he wasn’t the one who started it. Mindful of being a teenaged upstart in the company of such seasoned track deities as Jesse Owens and Glenn Cunningham, Louie curbed his coltish impulses and began growing a mustache. But he soon noticed that practical y everyone on board was “souvenir col ecting,” pocketing towels, ashtrays, and anything else they could easily lift. “They had nothing on me,” he said later. “I [was] Phi Beta Kappa in taking things.” The mustache was abandoned. As the voyage went on, Louie and the other lightfingers quietly denuded the Manhattan.

Everyone was fighting for training space. Gymnasts set up their apparatuses, but with the ship swaying, they kept getting bucked off. Basketbal players did passing dril s on deck, but the wind kept jettisoning the bal s into the Atlantic. Fencers lurched al over the ship. The water athletes discovered that the salt water in the ship’s tiny pool sloshed back and forth vehemently, two feet deep one moment, seven feet the next, creating waves so large, one water polo man took up bodysurfing. Every large rol heaved most of the water, and everyone in it, onto the deck, so the coaches had to tie the swimmers to the wal . The situation was hardly better for runners. Louie found that the only way to train was to circle the first-class deck, weaving among deck chairs, reclining movie stars, and other athletes. In high seas, the runners were buffeted about, al staggering in one direction, then in the other. Louie had to move so slowly that he couldn’t lose the marathon walker creeping along beside him.

Courtesy of Louis Zamperini