Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience and Redemption (9 page)

Read Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience and Redemption Online

Authors: Laura Hillenbrand

Tags: #Autobiography.Historical Figures, #History, #Biography, #Non-Fiction, #War, #Adult

S ix

The Flying Coffin

AS JAPANESE PLANES DOVE OVER OAHU, MORE THAN TWO thousand miles to the west, a few marines were sitting in a mess tent on Wake Atol, having breakfast. Extremely smal , lacking its own water supply, Wake would have been a useless atol but for one enormous attribute: It lay far out in the Pacific, making it a strategical y ideal spot for an air base. And so it was home to one runway and about five hundred bored American servicemen, mostly marines. Aside from the occasional refueling stopovers of Pan American World Airways planes, nothing interesting ever happened there. But that December morning, just as the marines were starting on their pancakes, an air-raid siren began wailing. By noon, the sky was streaked with Japanese bombers, buildings were exploding, and a few startled men on less than three square miles of coral found themselves on the front in the Second World War.

Al over the Pacific that morning, the story was the same. In less than two hours over Pearl Harbor, Japan badly wounded the American navy and kil ed more than 2,400 people. Almost simultaneously, it attacked Thailand, Shanghai, Malaya, the Philippines, Guam, Midway, and Wake. In one day of breathtaking violence, a new Japanese onslaught had begun.

In America, invasion was expected at any moment. Less than an hour after the Japanese bombed Hawaii, mines were being laid in San Francisco Bay.

In Washington, Civil Defense Minister Fiorel o La Guardia looped around the city in a police car, sirens blaring, shouting the word “Calm!” into a loudspeaker. At the White House, Eleanor Roosevelt dashed off a letter to her daughter, Anna, urging her to get her children off the West Coast. A butler overheard the president speculating on what he’d do if Japanese forces advanced as far as Chicago. Meanwhile, just up Massachusetts Avenue, smoke bil owed from the grounds of the Japanese embassy, where Jimmie Sasaki worked. Staffers were burning documents in the embassy yard. On the sidewalk, a crowd watched in silence.

On the night of December 7–8, there were four air-raid alerts in San Francisco. At Sheppard Field air corps school, in Texas, spooked officers ran through the barracks at four A.M., screaming that Japanese planes were coming and ordering the cadets to sprint outside and throw themselves on the ground. In coming days, trenches were dug along the California coast, and schools in Oakland were closed. From New Jersey to Alaska, reservoirs, bridges, tunnels, factories, and waterfronts were put under guard. In Kearney, Nebraska, citizens were instructed on disabling incendiary bombs with garden hoses. Blackout curtains were hung in windows across America, from solitary farmhouses to the White House. Shocking rumors circulated: Kansas City was about to be attacked. San Francisco was being bombed. The Japanese had captured the Panama Canal.

Japan gal oped over the globe. On December 10, it invaded the Philippines and seized Guam. The next day, it invaded Burma; a few days later, British Borneo. Hong Kong fel on Christmas; North Borneo, Rabaul, Manila, and the U.S. base in the Philippines fel in January. The British were driven from Malaya and into surrender in Singapore in seventy days.

There was one snag: Wake, surely expected to be an easy conquest, wouldn’t give in. For three days, the Japanese bombed and strafed the atol . On December 11, a vast force, including eleven destroyers and light cruisers, launched an invasion attempt. The little group of defenders shoved them back, sinking two destroyers and damaging nine other ships, shooting down two bombers, and forcing the Japanese to abort, their first loss of the war. It wasn’t until December 23 that the Japanese final y seized Wake and captured the men on it. To the Americans’ 52 military deaths, an estimated 1,153 Japanese had been kil ed.

For several days, the captives were held on the airfield, shivering by night, sweltering by day, singing Christmas carols to cheer themselves. They were initial y slated for execution, but after a Japanese officer’s intervention, most were crowded into the holds of ships and sent to Japan and occupied China as some of the first Americans to become POWs under the Japanese. Unbeknownst to America, ninety-eight captives were kept on Wake. The Japanese were going to enslave them.

——

Though Louie had been miserable over having to rejoin the air corps, it wasn’t so bad after al . Training at Texas’s El ington Field, then Midland Army Flying School, he earned superb test scores. The flying was usual y straight and level, so airsickness wasn’t a problem. Best of al , women found the flyboy uniform irresistible. While Louie was out walking one afternoon, a convertible fringed in blondes pul ed up, and he was scooped into the car and sped off to a party. When it happened a second time, he sensed a positive trend.

Louie was trained in the use of two bombsights. For dive-bombing, he had a $1 handheld sight consisting of an aluminum plate with a peg and a dangling weight. For flat runs, he had the Norden bombsight, an extremely sophisticated analog computer that, at $8,000, cost more than twice the price of the average American home. On a bombing run with the Norden sight, Louie would visual y locate the target, make calculations, and feed information on air speed, altitude, wind, and other factors into the device. The bombsight would then take over flying the plane, fol ow a precise path to the target, calculate the drop angle, and release the bombs at the optimal moment. Once the bombs were gone, Louie would yel “Bombs away!” and the pilot would take control again. Norden bombsights were so secret that they were stored in guarded vaults and moved under armed escort, and the men were forbidden to photograph or write about them. If his plane was going down, Louie was under orders to fire his Colt .45 into the bombsight to prevent it from fal ing into enemy hands, then see about saving himself.

In August 1942, Louie, graduated from Midland, was commissioned a second lieutenant. He jumped into a friend’s Cadil ac and drove to California to say good-bye to his family before heading into his final round of training, then war. Pete, now a navy chief petty officer stationed in San Diego, came home to see Louie off.

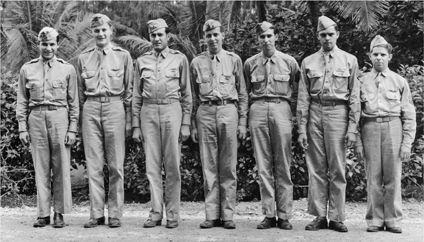

On the afternoon of August 19, the Zamperinis gathered on the front steps for a last photograph. Louie and Pete, dashing in their dress uniforms, stood on the bottom step with their mother between them, tiny beside her sons. Louise was on the verge of tears. The August sun was sharp on her face, and she and Louie squinted hard and looked slightly away from the camera, as if al before them was lost in the glare.

A last family photograph as Louie leaves to go to war. Rear, left to right: Sylvia’s future husband, Harvey Flammer; Virginia, Sylvia, and Anthony Zamperini. Front: Pete, Louise, and Louie. Courtesy of Louis Zamperini

Louie and his father rode together to the train station. The platform was crowded with uniformed young men and crying parents, clinging to one another, saying good-bye. When Louie embraced his father, he could feel him shaking.

As his train pul ed away, Louie looked out the window. His father stood with his hand in the air, a wavering smile on his face. Louie wondered if he’d ever see him again.

——

The train carried him to a perpetual dust storm known as Ephrata, Washington, where there was an air base in the middle of a dry lakebed. The lakebed was on a mission to bury the base, the men, and al of their planes, and it was succeeding. The air was so clouded with blowing dirt that men waded through drifts a foot and a half deep. Clothes left out of duffel bags were instantly filthy, and al of the meals, which the crews ate outside while sitting on the ground, were infused with sand. The ground crews, which had to replace twenty-four dirt-clogged aircraft engines in twenty-one days, resorted to spraying oil on the taxiways to keep the dust down. Getting the lakebed off the men was problematic; the hot water ran out long before the men did, and because the PX didn’t sel shaving soap, practical y everyone had a brambly, dust-catching beard.

Not long after his arrival, Louie was standing at the base, sweating and despairing over the landscape, when a squarish second lieutenant walked up and introduced himself. He was Russel Al en Phil ips, and he would be Louie’s pilot.

Born in Greencastle, Indiana, in 1916, Phil ips had just turned twenty-six. He had grown up in a profoundly religious home in La Porte, Indiana, where his father had been a Methodist pastor. As a boy, he’d been so quiet that adults must have thought him timid, but he had a secret bold stripe. He snuck around his neighborhood with bags ful of flour, launching guerril a attacks on windshields of passing cars, and one Memorial Day weekend, he wedged himself into a car trunk to sneak into the infield of the Indy 500. He had gone to Purdue University, where he’d earned a degree in forestry and conservation. In ROTC, his captain had cal ed him “the most unfit, lousy-looking soldier” he’d ever seen. Ignoring the captain’s assessment, Phil ips had enlisted in the air corps, where he’d proven to be a born airman. At home, they cal ed him Al en; in the air corps, they cal ed him Phil ips.

The first thing people tended to notice about Phil ips was that they hadn’t noticed him earlier. He was so recessive that he could be in a room for a long time before anyone realized that he was there. He was smal ish, short-legged. Some of the men cal ed him Sandblaster because, said one pilot, “his fanny was so close to the ground.” For unknown reasons, he wore one pant leg markedly shorter than the other. He had a tidy, pleasant, boyish face that tended to blend with the scenery. This probably contributed to his invisibility, but what real y did it was his silence. Phil ips was an amiable man and was, judging by his letters, highly articulate, but he preferred not to speak. You could park him in a crowd of chattering partygoers and he’d emerge at evening’s end having never said a word. People had long conversations with him, only to realize later that he hadn’t spoken.

Russel Al en Phil ips. Courtesy of Karen Loomis

If he had a boiling point, he never reached it. He rol ed along with every inexplicable order from his superiors, every foolish act of his inferiors, and every abrasive personality that military life could throw at an officer. He dealt with every manner of adversity with calm, adaptive acceptance. In a crisis, Louie would learn, Phil ips’s veins ran icewater.