Read Valley of the Shadow: A Novel Online

Authors: Ralph Peters

Valley of the Shadow: A Novel (14 page)

Didn’t see any batteries lined up. That was queer. Yankee artillery was a monstrous thing, devastating, plentiful. Yet, here … he could spot only two guns for certain and what might or might not have been a third set back.

What if the Yankees had kept their batteries hidden? To spring a surprise?

He said nothing of his fears to his subordinates. He never did. And far too much of the day had burned away to spend time on debate and deliberation.

Drawing up on a mild rise, he waited for his brigadiers to settle around him and soothe their horses. Every equine mouth was green with foam: Their march had been hurried, their scouting fevered.

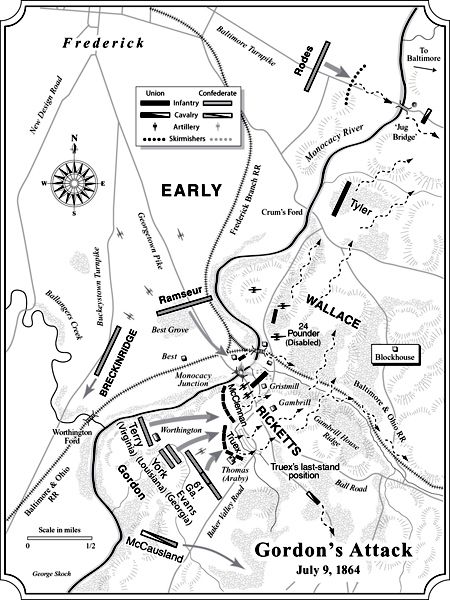

“Well, gentlemen … your eyes see as well as mine. There is no good way to do this.” He considered his three brigadiers: Evans, the man he trusted most, with his parson’s smile and fervent heart, commanding Gordon’s old brigade of Georgians. Zeb York, with the remains of ten Louisiana regiments combined under his command, their rolls not amounting to half of a full brigade. Reared in Maine, but seduced by Louisiana, York had been one of the few truly wealthy men to go to war and stick it out. It was said he owned—or had owned, given present conditions in Louisiana—nigh on two thousand slaves. This day, the men he led numbered barely a third of that. But York would fight like a bull, charging ahead. And Bill Terry, newly made a brigadier general, somehow combined intelligence and gallantry, two qualities the war had taught Gordon were generally exclusive of one another. Terry’s Virginia Brigade gathered in the survivors of fourteen regiments shattered in the Wilderness or bled out at Spotsylvania. Especially Spotsylvania.

Clem Evans would fight with heart, York with his knuckles, and Terry with his brain. Gordon had a purpose for each man.

“We’re going to advance

en echelon,

from the right. Overlap their left, spook them into weakening their center along that crest.”

“Looks like that could require some serious spooking,” Zeb York told him. York retained the wealthy man’s sense of a God-given right to speak up. Gordon knew it, expected it, and tolerated it. York followed orders, that was the thing that mattered.

“Well, that’s where you’ll play your part, Zeb. But you’re running on ahead of me.” Gordon fixed his eyes on Evans. “Clem, you’ll be on the right, you’ll go out first.” He saw the flicker of doubt in Evans’ eyes, but it was only a flicker, soon snuffed out. “The Georgia Brigade’s going to face the worst of it, I understand that. But I need you to keep the pressure on their left. Zeb here will be in trail, on

your

left. He won’t dally now, just give the Yankees time enough to issue the wrong orders.” Looking from one man to the other, he said, “I expect you to break both of those Yankee lines. Between the two of you.”

Arching his back, Gordon stretched before resuming the perfect posture he kept in the saddle. “Bill, you’re my reserve. But I want your Virginians positioned to move

en echelon,

too, should the need arise. You’ll be on Zeb’s left, toward the river. Just keep your eyes wide open and be ready.”

“Virginia’s

always

ready, sir.”

Gordon almost snapped, “Not on the twelfth of May, you weren’t,” but restrained himself. Holding his tongue was often a trial, but only a fool made an enemy of a man who might one day prove a useful friend.

“Indeed,” Gordon told him, “indeed. I count myself the child of unsullied fortune in the privilege of commanding these three brigades. I hold none more valiant in all the armies of the Confederacy.” He smiled slyly, though not meanly. The slyness was meant to be seen and appreciated. “Of course, we’ll see who shines brightest today. Questions, gentlemen?”

“Thought you were going to get rid of that old red shirt?” Zeb York asked. “You stick out like the Queen of Sheba herself, get yourself killed. Then where’d we be?”

Gordon smiled the perfect smile again. “Why, I expect some grateful brigadier would get a promotion.” He twisted the smile from easy to wry. “Need y’all to be able to find me, when you seek my counsel.”

“Yankees don’t seek you first.”

“That’s your job, Zeb. To keep those blue-bellies off me.” He put the smile back in the smile chest. “All right, gentlemen … you will form your brigades behind that hill. Bill, you won’t stretch that far up, so keep your men back of the barn a ways. Flags down. Until you advance.”

Terry nodded.

As he surveyed the faces before him—none jovial now, each earnest—he paused, for a hair-split, at his brother’s eyes. Gene was to be a major, if spared this day. Gordon wanted the younger man to live for that promotion and long thereafter. But Eugene would have to do his duty at Clem Evans’ side.

He had noted his brother’s worried look when York raised the matter of the flannel shirt. Fact was, Gordon didn’t care for the garment. Even washed thin, it was too hot for the day, and turning back the sleeves hardly made a difference. But the men loved to see him in it. And they certainly saw him.

It continued to amuse, if not amaze, him how much his fellow officers and even his own kin failed to understand: Even a fearful man would die for a general in a red shirt. A. P. Hill understood that, but few others did. Early certainly didn’t.

Damn Early, though. The army should have been a dozen miles down the road by now. They’d lost a day, thanks to that shabby money-raking in Frederick and Ramseur’s knack for tying himself in knots. And damn that fool McCausland, for waking the Federals up to their open flank. And damn the sorry Maryland dirt underfoot, the whole fastidious, interfering, Negro-worshipping Union.

It was going to be a bloody, bloody day.

Gordon had saved his warmest smile for the last, a smile that promised intimate friendship with every man it fell upon. He believed that his hero, that other Ulysses—so unlike the beast in Union blue—would have donned just such a smile to win over Achilles, Agamemnon, or Menelaus.

“Not a man here has ever let me down,” Gordon announced. “And I know you never will.” He tugged on the reins just enough to make his beloved black horse prance. “Let’s kill us some Yankees.”

3:15 p.m.

Intersection of the Georgetown Pike and Baker Valley Road

Ricketts turned to face Wallace, who had just dismounted beside him. He realized that his temporary commander had come down to the road, rather than summon him, to shorten the interruption of his work re-forming his lines. Wallace seemed a considerate sort, gentlemanly, stuffed with brains, a dreamer. They were different types, almost opposites, but Ricketts

liked

this man who was about to destroy his division.

Moving clumsily, obviously exhausted, Wallace stepped close. “Let us walk for a moment, General Ricketts. Apart from the men. I shan’t take much of your time.”

There wasn’t much “apart” to be had, between the dressing ranks and sergeants all but hurling ammunition. Litter bearers moved back and forth like a two-way column of ants, depositing their cargoes and fetching more. Inevitably, a wagon had overturned, narrowing the road. Clutching his shoulder, the driver cursed magnificently.

The two generals stepped along, gesturing to the men to remain at ease. The shade, what little there was, had magnetic force, but by unspoken agreement, Ricketts and his companion left it to the powder-smeared, sweat-gripped soldiers.

“Your troops have done splendidly,” Wallace told him.

“Except for those two blasted regiments. God knows where the devil they are right now.” He had sensed, with finality, that those precious regiments and strayed companies would not arrive in time to affect the outcome.

Of course, the outcome would not have been changed, anyway. Only the fight’s duration was in dispute.

“I’m sorry,” Wallace said. “The railroad seems to have let us down today.”

Ricketts shrugged. “Fortunes of war.” Mind back on business, he said, “I’ve stripped the riverfront. Your boys will have to hold it. I’ve pushed out a heavy skirmish line again. Changed its orientation, of course. I learned that lesson. Main line’s still by the house, best ground. Flank’s refused by one regiment, all I can spare from the firing line.” He gestured at the men filling the hollow that cradled the Pike. “Reserve’s down here, two regiments. The Rebs will have to pound their way through, and they’ll pay the devil’s wages.”

He knew what Wallace was thinking. It would be the very thought he harbored himself:

If

they come the way we think they’ll come.

“There was a mounted party on a scout,” Ricketts added. “All officers, judged by the gait of their horses. Postures, too, that high-and-mighty way most of them have. Rode the length of the hill ten minutes ago.”

“I saw them,” Wallace said. “Infantry commanders would be my guess. Weighing courses of action.”

“They’ll come that way, all right. No real choice.”

Wallace nodded. “It’ll be soon. They’re pressing harder across the river, like they mean it this time. Not sure how much longer our boys can hold, they’re in a bind.”

“Those Vermont boys are stubborn.”

“I made a mistake. The bridge, the fire.”

For the first time in hours, perhaps aeons, Ricketts smiled. “Generals don’t

make

mistakes, sir. Didn’t anyone let you in on the secret? First thing a fellow learns when he gets to West Point.” Voice almost jovial—he recognized the hilarity that sprang from desperation—he added, “Never made a single mistake myself.”

Wallace smiled, too. But Ricketts thought, for a flashing moment, of the wretched court-martial of Fitz John Porter, of his own shabby part in it. Mistakes? What was a man’s life but a trail of mistakes?

Letting his smile fall away, Wallace said, “We’ve cost them a day. That’s something.”

“Cost them a good bit more, before we’re done.”

“If … I ordered you to withdraw now … you could save your division. There’s still time for an orderly withdrawal. I doubt the Rebs would contest it. They just want us out of the way.”

It was a tempting thought. A wonderful thought.

“We haven’t been beaten yet,” Ricketts said.

“We will be,” Wallace said, almost whispered.

“Yes. But we haven’t been. Not yet.”

“You’ll lose half your division. At least.”

“You told me yourself that every hour counts.”

Wallace appeared taut with nerves, half-starved, dark eyes sunken, and shoulders caved like an old woman’s under a shawl. Not the way the illustrated papers portrayed heroes. But Ricketts understood, thoroughly and clearly, that Wallace meant to stay and fight it out. With or without the men Ricketts commanded. He was trying to be just, but war mocked justice. The man was far too decent to be a general.

“It does,” Wallace said. “Every hour counts.”

“Then it’s my duty to contest the field.”

“God bless you,” Wallace said, faintly, enunciating each word.

Ricketts was tempted to say far more than was his habit, to lash out and damn the idiocy in Washington, the stubbornness of every general officer not present where they stood, the pigheadedness of government and the creatures who fed off its carcass like monstrous insects. Above all, he wanted to say, “I just hope to Christ in Heaven all this is worth it, that somebody in Washington has decided by now to step away from the bar of Willard’s Hotel and do their duty.”

But Wallace doubtless harbored the same thoughts; there was no point in speaking aloud. The men might hear.

“Best see to my lines,” Ricketts said brusquely. “Rebs will be coming along.”

“General Ricketts? In case we … should become separated. I want to thank you.” Wallace held out his hand.

Ricketts accepted the paw, but the time for genteel communion had passed them by. He nodded toward his begrimed men in their shabby uniforms.

“Thank them.”

3:30 p.m.

Worthington farm

“Keep your alignment, men,” Lieutenant Colonel Valkenburg called as he rode between their lines. “Keep up your alignment.”

The sound of nigh on a thousand men advancing seemed to hush all else in the world. Even the thump of the guns on the far bank faded. Nichols believed he could hear his heart, fearful and no denying it.

The first field they crossed had been stripped bare of crops, leaving a man with his own feeling of nakedness. They were still out of range of the Yankee rifles, but exposed for all to see, and each step brought them closer to whatever the Lord had in mind. Horn-hard feet and rough shoes slapped baked earth, raising pale dust to bother throats consigned to the second rank. Sweating untowardly, like a fat man, Nichols felt shrunken.

In the next field, yet uncut, the

shish-shish-shish

of feet and calves pushed through ripe wheat with the sound of a thousand scythes.

The day was hot, bright blue, gold, green-rimmed, marred here and there by smoke. Despite his wash of sweat, Nichols felt light, with his blanket roll and haversack left behind in the trees, every man going forward with just his fighting tools. Still, he sensed a ghost where the blanket had gripped, the wet cloth cooling now, despite the sun. He’d learned so much he hoped he lived to tell it, how a man could be hot and chilled at once, sick with fear and ready to kill with fury.