Valley of the Shadow: A Novel (17 page)

Read Valley of the Shadow: A Novel Online

Authors: Ralph Peters

Nichols stood. Dumbly. Out of worldly ambition of any kind.

There were Yankee prisoners in numbers enough to work all the fields in Georgia. Powder-blackened men with sour expressions, some weeping, though not from fright or weakness, a man could tell that. Their fear of death had passed, replaced by lesser dreads.

A broken-toothed fellow in brown homespun came smiling up to Nichols, long, greased hair gone thin and hanging below a black hat a witch might have worn in a picture book.

“Who’re you with, there, sonny?”

“Sixty-first Georgia,” Nichols said proudly, defiantly. “Evans’ Brigade, General Gordon’s Division.”

The ugly mouth cackled and formed new words: “Bet y’all glad Ramseur come to save you, ain’t you now?”

Nichols knocked the man down.

5:30 p.m.

Thomas farm

Early dismounted on the crest, amid the dead and dying.

“Stay in the saddle, Sandie,” he said. His voice carried no hint of sorrow or remorse, only cold determination. “You ride off yourself, send out couriers. Tell all of them—Gordon, Ramseur, Rodes–I said not to get carried away. No more prisoners, I can’t herd any more. Let them run off, I don’t choose to be encumbered. This army already favors a band of gypsies.”

“Yes, sir. Anything else?”

“Tell McCausland he may find the road to Washington open now, if he cares to look. And if he doesn’t mind too awfully much, I’d appreciate him doing what I goddamned well ordered that fool to do this morning. He’s to get on down that road and keep on going.”

“I believe he’s already dispatched most of his command, sir.”

“Tell him to send off the rest.”

“They’re caring for their wounded.”

“Let somebody else do it. God almighty, I’m going to get some use out of his clapped-up jockeys yet.” He chewed a cud that wasn’t there, a ghost of old tobacco. “Any word from Johnson?”

“No, sir. But he should be a good ways along now, putting a scare in folks.”

Early tested a fallen Yankee with the tip of his boot. “He won’t get within fifty miles of Point Lookout.” He pondered for a moment. “Crazy idea. No sense being too hard on Johnson on that count, fool though he may be. You go on now.”

Early squatted. The way common soldiers did when they were about to loot a corpse. But he didn’t touch the body, only looked at it—the hole in the temple nearly the size of a dollar, the blood darkened almost brown, the lazy flies, gorged, feasted, surfeited.

“Damned Sixth Corps. Looks like someone in Washington done woke up.” He lifted his eyes to the staff men gathered around. “Going to have to get an early start tomorrow morning.”

5:30 p.m.

Baltimore road, east of the Stone Bridge

Wallace could not speak at first, but needed to calm himself and catch his breath from the pounding ride. He had been relieved to find General Tyler and his men exactly where they were supposed to be, but the level of firing just across the river, toward Frederick, suggested that few were apt to be there much longer.

Wearing a harried look, Erastus Tyler waited for his superior to speak first.

“Well, we’ve lost,” Wallace said.

Tyler nodded.

“We’ve lost, but we cost them a day. A full day.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Ras, you

must

hold the bridge, keep the Rebels from crossing. This road’s all we have left. Ricketts put up a remarkable fight, we can’t let his survivors be cut off.”

Tyler, too, appeared wearied. Stained. Not just with the salt that collected from a man’s sweat, but by life. They all were.

“Do my best, sir. Men held fine all day. Only a few ran off. But they’re tired now. Unsteady.”

“We’re all tired.”

“Just telling you the truth, sir. They will not hold against a determined attack. Some will fight, but not enough. And not long enough. Not with everybody else running. Panic’s catching, you know that.”

And running his men were, Wallace had to face it. He had waited too long to withdraw, zealous for each additional minute, tallying the hours as a child might, selfish, blinded. When he left the battlefield, with Ross tugging his mount’s bridle to make him go, he had fled a debacle, with his own men disappearing and Ricketts’ remaining soldiers all but surrounded.

Ricketts. The Republic owed that man a debt.

And Alexander had brought off his guns. Even that howitzer.

Not everyone had quit, there had been heroes. Many of them. And officers were still out there, along the line of retreat, attempting to lead the remnants of companies and regiments amid the confusion and the Rebel pursuit, to save what could be saved.

Wallace knew that he needed to move on himself, to rally as many men as he could, to gather numbers sufficient to block the road to Baltimore at whatever point presented itself, to fight again. In case he had been wrong about that, too, and Early planned on burning the docks and warehouses, the rail yards and the arsenal.

He had to see to countless tasks, but he only slumped in the saddle, allowing himself a stolen moment of rest, overtaken by the day, overwhelmed at last. He just wanted to sleep. Between clean sheets.

How many men had his obstinacy killed? And how many of those deaths had been unnecessary, offerings made too late to affect the result, men left to die when he should have begun to clear the field and spare what lives he could?

Selfishness. Pride. Vainglory. So many sins were disguised by the fine word

duty

.

Waking himself, Wallace told Tyler, “I’m depending on you, Ras. Hold the bridge. As long as you can. Do your best. Give me two hours. One hour.”

And Wallace turned back toward his shattered army.

7:00 p.m.

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, east of Monocacy Junction

Ricketts and his staff followed the rail line. The Reb pursuit appeared to have slackened and the men let their winded horses slow to a walk for a stretch.

He had waited too long, making the wrong guesses toward the end. The Rebs had overwhelmed them, that was true. But Ricketts already saw the things he might have done differently.

Would

do differently. Another time.

Would he be allowed another time? With his wrecked division?

He hoped that Wallace had escaped the Rebs. The damned fool. A damned fool, and a good man. For any blunders he might have made, Wallace had done a dozen and more things right. He had seen what needed doing and had done it, where a timid man, one thinking of his career, would have found excuses so convincing they were sure to get him promoted. Together, they had bought a day for Washington.

And

bloodied Early’s army.

His own losses were terrible, though. He would not know the true numbers for days, as soldiers left to save themselves filtered back in to their commands, as they always did. But the numbers would be grim, not least those taken prisoner. He barely had escaped himself, refusing his staff’s entreaties to ride off until the Rebels had almost boxed them in. He believed that Truex had gotten off the field, too. But the toll of regimental officers looked to be crippling.

They passed a slump-shouldered group of soldiers—his men, judging by their hard-worn uniforms. Most had brought off their rifles, but not all of them.

“You men gave them the devil today,” Ricketts told them. “And we’ll give them the devil again, when we have the chance.”

“Strikes me the Devil got his own both ways,” a wag called out. “Any of you officers got a spare beefsteak?”

That was all right. When men could joke, it meant they were not broken. The division had been shattered, but not destroyed. The men would come in. And those two missing regiments would be found, with hell to pay when he found the man responsible for their absence from the field.

He worried a bit about his future, but not overly much. He had been the subordinate, and his division had fought handsomely. He was unlikely to bear any blame. But it had been, after all, a defeat—no matter its contribution—and the entire effort might be portrayed as foolhardy by those safe behind mahogany desks in Washington.

He

was unlikely to suffer any consequences. But Wallace? No breed of man was more vindictive than those who shied from battle in the rear. If Wallace had enemies, this would be their hour.

Off to the right, ahead of them, firing erupted.

“Best pick up the pace, sir,” an aide counseled.

9:30 p.m.

Thomas farm

Nichols sat. It was all he could do, all he wanted to do, to the extent he felt any least desire to do anything. He had eaten, Yankee food, of which there was plenty. Brined pork, beans, and crackers without weevils. He had eaten like a machine, spooning up the food steadily, not tasting much, filling the empty space in his belly as if that might fill the other emptiness.

After he had knocked down Ramseur’s man, the 61st Georgia and the 12th Georgia Battalion were ordered to stop where they were and leave chasing Yankees to others. Wandering back a stretch over the field, he had come upon Tom Nichols of Company A, a namesake but no kin. Tom’s brains were hanging out of his temple, and the wounded man pawed one-handed at the slops, either trying to shove them back in or brush them away from his skull. Nichols knelt down to see if there was anything he could do, trying not to show the horror he felt, and helped Tom to a drink from his canteen. It was almost as if Tom had already turned hant, for he seemed to feel no pain. He still had a scrap of his wits, though.

“If I can get back to Virginia,” the dying man declared, “just get back to Virginia … get me a horse…” His eyes met Nichols’, but it was beyond knowing what Tom really saw. “Never going to cross the Potomac again, never going to cross the Potomac again, never.” He went back to smearing his brains across his temple.

Nichols sat with him until a pair of litter bearers appeared to take him to a field surgery. It was clear from their looks, from any expertise they had acquired, that Tom was a goner. But Nichols had already known that.

“… a horse…,” Tom said, the last words Nichols heard from him.

He meant to pray thereafter, to thank the Lord for delivering him this day, but he kept putting it off. After trying to banter with him, to cheer him, Lem Davis and Dan Frawley had let him alone, just keeping watch on his doings from a distance. He didn’t resent that, didn’t feel anything about it. When Tom Boyet fetched his blanket roll and haversack for him, setting both down by his side, he had lacked the means, the courtesy, to thank him.

Nichols wanted to see his mother again. He wanted to live that long. Tom would not live that long.

He knew he should be thankful that so many of his brethren, his close brethren, had survived. But he felt the death of Lieutenant Colonel Valkenburg unreasonably, deeply, seeing him fall from his saddle again and again, until it was maddening. And Colonel Lamar, too, it didn’t seem fair. He hoped the colonel had died in grace, forgiven his last profanities. Lieutenant Mincy stuck in his thoughts as well, although it was told he might live to drink coffee again, surviving his third wound, a blessing. Nichols meant to pray for Mincy, too. And for General Evans, who also promised to live. But it was just too hard to move, to part his lips.

He sat in the gloaming, shirking his duty to help out with the wounded, his own kind and the Yankees.

“It’s a terrible thing,” he said suddenly, speaking out loud. “It’s a terrible thing.”

But had a man asked, he could not have told him what that terrible thing was.

When the roll was called, in the virgin dark, the 61st Georgia, which had gone into battle with one hundred and fifty men, answered with fifty-two voices.

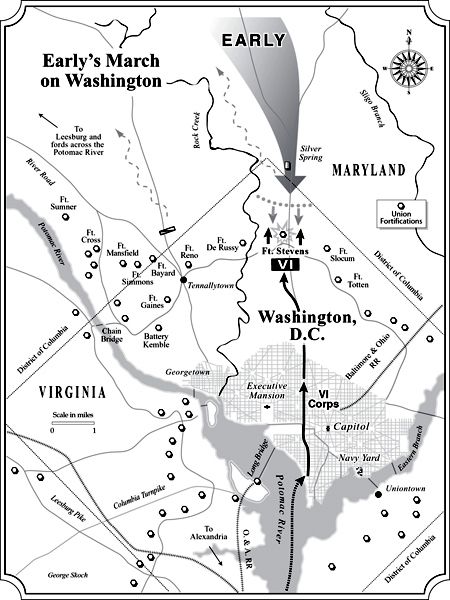

July 11, 4:00 p.m.

Northern outskirts of Washington

Gordon stared at the Capitol’s dome in the distance. Gilded by the afternoon sun, the great bell rose above the city and its girdle of forts, a fabulous dare. Gordon’s longing to seize it, to violate those precincts, was as palpable as the desire he’d felt toward unruly women in his bachelorhood.

The plank-slap sound of skirmishing troubled the nearby fields and apple orchards. Artillery shells, ill-aimed, thrilled overhead, exploding randomly in the army’s rear.

“We should attack now,” he said. “With every man we’ve got.”

Astride his sweat-slicked horse, Early snorted. “And just how many men do you think we’ve got?”

“Enough. If we go in now.” Gordon’s voice burned.

“This army’s stretched back twenty miles, heat-sick and dropped by the roadside.”

“My men

cheered,

when they caught sight of that dome.”

“Ha! Three men and a dog?” Early spit amber juice. “I saw your boys stagger up. Half-dead of thirst.”

Gordon gazed across the fields to the earthen fort and its entrenched wings, the last barrier between his troops and the Capitol. “The Federals are thin. They haven’t got enough men up. There’s a stretch on the right that’s all but undefended, I rode out there myself.” He turned to his fellow division commanders, Ramseur and Rodes, somber men covered in dust, their uniforms traced with sweat-salt.