Valley of the Shadow: A Novel (20 page)

Read Valley of the Shadow: A Novel Online

Authors: Ralph Peters

Old Jube could hold his liquor, but it never helped his mood the morning after. No orders had reached Gordon, either to attack or to prepare for a withdrawal, and at last he’d run out of patience. He believed more strongly than ever that an attack would end in defeat, if not disaster. He hoped to reason with Early, fearing that an assault was now a question of honor for the old soldier.

The situation wanted extreme delicacy. The last thing Gordon intended was to prod Early to attack on a point of pride. Be as Ulysses, he told himself, employ the guile of the ultimate survivor. Never injure the pride of Agamemnon.

“Goddamned Sixth Corps,” Early said by way of greeting. “I knew it, I goddamned well knew it. Look at the goddamned flags.”

The commanding general did not sound in good spirits.

“Yes, sir,” Gordon said. “Rode out for a look myself. Lines are just plain bristling.”

“Goddamned French wine,” Early said. “Not fit for man or beast.” He looked at Gordon. “Change your mind again? Want to attack those sonsofbitches, after all?”

Choosing his words with care, Gordon said, “Reckon I had enough of the Sixth Corps on the Monocacy. I’d be honored to pass along the privilege, sir.”

“Hah! Taught them a lesson, though.”

“That we did. We did, indeed.” Gordon smiled his best Ulysses smile, perfected in the looking glass of life. “I doubt they’ll denude this fair city of troops again. And those are troops that will never be free to join Meade and Grant. They might as well be our prisoners. Or dead.” Again, Gordon selected his words with precision. “Sir, if we’ve had our differences … my hat’s off to you for bringing the army this far. Such a small force, really, it’s—”

“It’s a goddamned shame, that’s what it is. Come so close. Those Sixth Corps sonsofbitches…” Early offered Gordon a cockeyed look and let his high-pitched voice climb even higher. “What do you think would happen if we went at ’em? Right now? Bust right through and march into the city?”

“We’d get in, but never get out.”

A succession of looks, none promising, crossed Early’s features. Then he appeared to slump, inside and out. “Going to be another man-killing scorcher,” he muttered. “Damnable weather, damnable.”

He met Gordon’s gaze, and despite any lasting effects of the flood of wine he’d drunk, Early’s eyes showed that brilliant spark that redeemed many a sin and drew good value from each tribulation. Inside that bent frame, Early was

alive

. Gordon, of all men, could recognize it.

“Goddamn it, Gordon,” Early told him, “you’d be an easier man to like if you’d just be wrong now and then.” He shook his head. “Grand fight on the Monocacy. If I haven’t told you that.”

“You haven’t.” Gordon smiled. But when Early grinned in return, Gordon sobered again. “It cost me.”

Early nodded, looked away. “I know. You and Johnny Lamar. Friendship. Hah. Always found it easier not to have too many friends. Plays hell with a fellow’s way of thinking.” He raised the field glasses to his chest, then lowered them again. “Any more word on Clem Evans?”

“He’ll live to fight another day. If there’s no infection. Going to be hurting, though.” It was Gordon’s turn to shake his head. “Fool had a packet of straight pins in his pocket. Bullet hit the pins, shattered them. He’ll be drawing out bits for years, I don’t envy Clem the discomfort.”

“What the devil was he toting pins for? Like a damned washerwoman.…”

Gordon shrugged. “Fanny tells me good steel pins have gotten hard to come by. Been looking out for a pack or two myself.”

Early curled his lips, seeking his old, safe irascibility. The effort failed. “Have we come to that?” he asked Gordon earnestly. “Generals scavenging pins?”

It dawned on Gordon that there would be no attack. Early had already made his decision, but couldn’t yet speak the words.

A Yankee gun opened from one of the redans. A cannonade followed, with the shells falling short or otherwise straying, noisy, spendthrift, and impotent.

“Guess the Sixth Corps didn’t bring their artillery. Schoolboys with ramrods, goddamned waste of powder,” Early said.

“Wouldn’t necessarily want to get much closer, though,” Gordon remarked. “Lot of guns on that line.”

“Blue-belly sonsofbitches have a lot of everything, that’s the problem. I’ll bet that bastard Grant don’t have any pins in his pocket.”

For the last time that day, but not for the last in his life, Gordon thought what a shame it was that they hadn’t attacked the moment they arrived the past afternoon. Even if it had only been with “three men and a dog.”

He wondered if, at that very moment, he was standing at the Confederacy’s last high tide.

“Oh, hell,” Early said. He turned in the saddle. “Sandie? Sandie Pendleton. You come up here, boy.”

Pendleton trotted up the few steps to Early. The chief of staff had kept a discreet distance from the generals’ conversation—yet close enough to overhear, Gordon was certain.

“Sir?”

“Orders.”

“Yes, sir.”

“All divisions are to remain in their present positions, postured for defense. Pickets will advance in strength to keep the Yankees occupied … but there will be no general attack. All subordinate commanders will prepare for a withdrawal after sunset.”

“Where to, sir?” Pendleton asked.

“Virginia, you damned fool.”

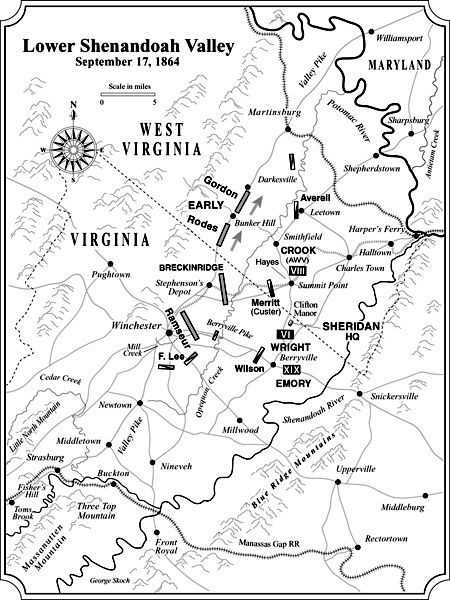

September 17, 1864

Rutherford house, Charles Town, West Virginia

He thought of apples. The day promised to be warm, but autumn’s chill was scouting in the forenoon, preparing for the invasion of cold to come. The cool air called apples to mind, the hard, mouth-puckering treasures of his childhood, attacked with strong teeth and a carefree heart. He liked his apples softer now, best when ladled up as pulp from a pot. Julia made fine applesauce. Her mother had let her learn that much from the kitchen slaves.

Well, if his wife wasn’t one for fancy cooking, that was all right. He wasn’t much for fancy eating. And Julia had made all else in his life bearable. He hoped, in the years ahead, to pay her back.

If Sheridan proved to have matters in hand, he intended to visit New Jersey for a night before returning to City Point and the war’s enormity. Look at the for-rent house his wife had picked and talk out the children’s schooling. Simple chores that war had transformed into pleasures.

Seated in a rocker, he lit another cigar and tossed the lucifer match down from the porch. Even a strong Havana could not defeat the sensations of memory. Those crisp, chill apples had been little glories, each bite sharp, and regret pierced him: He could no longer risk the cherished treats. His years alone in the Northwest had been hard, not least on his choppers. Nor had the years that followed been much kinder. Privilege had come to him too late for some things: He commanded mighty armies, but feared biting into the first apples of fall.

A rare mood of self-indulgence, almost a swoon, seized him that morning. He wanted Sheridan to appear so they might settle the campaign’s course, get the business moving. But sitting alone, unbothered, was a reprieve, reminding him of how strained life had become and of the pains he took not to reveal it.

Amid the clutter and clatter of yet another occupied town in another army’s rear and the dust of streets churned by laden wagons and caissons, he found himself gripped again by the force of memory, banishing for a little while the gore of the past five months and the stink of war, in favor of the scents of buried decades, the sweetly pungent autumn rot—so unlike the reek of rotting flesh—and the clean, cold winds that scoured the Ohio Valley. The master killer of his age, he had learned in a bloody school to value innocence.

A teamster passing the house cursed his beasts and found himself swiftly hushed. The man glanced back toward the porch in terror.

Yes, Grant thought, I am a terrible man. But I will make an end of this.

The two aides he had brought along guarded the front fence, shooing off gawkers and well-wishers. Around the captain and major, the provost marshal’s guards bristled with nerves. Such men, made small by war, saw dangers everywhere: partisans, raiders, assassins.

Grant didn’t worry. The tide had turned; he felt it. It was now a matter of finishing what was under way.

He didn’t know whether to admire the Rebs’ tenacity or to condemn their hopeless waste of lives.

Maybe both.

Bill, his manservant, eased around the side of the house and paused below the porch, smiling. Bill had magnificent teeth, although he was the older of the two of them.

Grant took the cigar from his mouth. “Come to stare now, too?”

“Nawsuh, nawsuh. Not till I sees some cause be worth the staring.”

Grant smiled, almost laughed. “Well, what is it, then?”

“Folks round here claims these Rutherfords be strong Secesh. Darkies ’fraid you going to burn this here house down.”

Canting his head an inch, Grant asked, “You saying they

want

me to burn it down? Talk straight.”

“Nawsuh, old Bill don’t have him one toe in that creek. Don’t think they’d mind, though. Say these here people Cunfeddrit as Genr’l Lee hisself, and then a mite. Black folk thought you be rememberin’ Chambersburg, what them Rebels done.”

“I don’t believe our hosts had a hand in that.”

“Secesh, all the same. That’s all I’m saying.” Bill shrugged. “Feeling desirous of a nice, hot dinner, Genr’l? Kind Miss Julia trouble you to eat? Share it with that heathen man you come to see?”

Grant laughed. “I don’t think General Sheridan will be staying.” Tapping his cigar, he added, “Neither will we.”

Pained to relinquish his vision of how the day should unfold, Bill shook his head, stamped once, and pawed the banister. “Mighty fine chickens hereabouts, say that. Yassuh. Spite all them soldiers a-lurking and a-looking, wonder a single hen be left alive.” He sighed. “But your mind made up once, it made up good. Learned that much, yassuh.”

“I’ll give General Sheridan your regards. You get along now, see everything’s packed and ready.”

“Should’ve let me shine up them boots. Miss Julia don’t like you looking like no field hand.”

“We go to Washington, you can shine ’em up.” With his cigar, Grant gestured toward the soldiers gathered in small groups along the street, all of them sneaking glances in his direction while pretending to be immersed in doubtful duties. “Last thing those boys need is another general with a high shine on his leathers.”

His manservant went off, muttering. Bill was nigh on the only man left who would always tell him the truth. Even if the truth came roundabout from the darkey’s mouth.

Bill and John Rawlins. Rawlins, too. With his weak lungs and worrisome cough. And Cump Sherman.

Grant flicked the butt into the yard. And there was Sheridan, already dismounted and striding up the street on his tiny legs, long arms dangling and chest thrust out like a pigeon’s breast, with a flat-crowned hat slapped down on his bullet-shaped head. Had the man not been such a priceless killer, he might have done for Paddy the Mug in a traveling comedy show.

Well, neither of us will win any prizes for beauty, Grant thought.

Grinning, Sheridan met Grant’s eyes and offered a gesture midway between a salute and a friendly wave. He came on fast, Little Phil, the way he always did, a man of profane energy, small and explosive. Still, he managed to cajole the loitering soldiers, threatening them gaily with duty in the line and an end to their easy living in the rear. And the soldiers loved him for it, it was the queerest thing. Sheridan excited soldiers so easily it was uncanny, and he made them discover reserves of courage and daring they had never dreamed they might possess. He’d killed Stuart and made the eastern cavalry.

Now Sheridan faced a greater task and had shown a hesitation that was unlike him. It was high time for a reckoning in the Valley: Cump had delivered Atlanta, shifting the political odds in the North, but Phil had to score a decisive victory here, before the election.

There could be no more raids on Washington, no more northern towns reduced to cinders. No more Chambersburgs.

What had Early been thinking? Was it mere spite? Hadn’t he seen that retribution must come?

Sheridan swung through the gate, greeting Grant’s aides by name. He tipped his hat, smoothed his mustaches, and let Grant feel the flash and force of eyes that looked faintly Chinese—eyes that could veer from merry to murderous quicker than a man could pull a trigger.

Spanking dust from his uniform, an instinctive courtesy, Sheridan leapt up the porch steps and said, “Sam, ain’t it fine to see you?”

Grant rose. “Where’s that big black nag of yours?”

“Getting a new shoe. Right foreleg. Month’s been hard.” Sheridan smiled. “You should ride him sometime. You’re the horseman.”

“Might not give him back.” Grant dropped the playfulness. “You’re smart enough to figure why I came up here.” He resisted drawing out the campaign plan buttoned in his pocket. Willing to give Sheridan first say.