Vermeer's Hat (21 page)

Authors: Timothy Brook

As the global community of smokers grew in the seventeenth century, though, they were uninhibited in expressing their delight

at discovering the pleasures of tobacco and have left behind many signs of their debt to its pleasures. One of the more exuberant

and unexpected is a tobacco ballet that the townspeople of Turin, Italy, staged in 1650. The first act of the ballet opens

with a troupe of townspeople dressed up in native costumes, dancing together and singing their praises to God for having given

humankind such a wonderful herb. The dramatist may have acquired the idea for this scene from illustrations of Native customs

in books about the Americas, which were popular with European readers. (Such exotic public displays of Native customs were

a fashion unto themselves, especially if one had actual Natives to perform them. Johann Maurits, who used the fortune he made

from plantations in Brazil to build the palatial residence in The Hague that is now the Mauritshuis museum, included in the

opening ceremonies a dance by eleven Brazilian Indians on the cobbled square out front.) In the second act of the tobacco

ballet, another troupe of townspeople appears. This group is dressed in costumes from all over the world. Surely the pantomime

would have called for someone to be in Chinese costume. There was a Chinese smoking on the Van Meerten plate, so there probably

was one in the Turin ballet. The show ends with these representatives of world cultures making their way together to a School

for Smoking, where they sit down and beg the first troupe to instruct them in the virtues of tobacco.

1. JOHANNES VERMEER,

VIEW OF DELFT

. Vermeer has chosen the subject of his sole large outdoor landscape carefully. This is the Kolk, the river harbour at the

southeast corner of Delft from which boats sailed down to the Rhine. A passenger barge is moored at the left, waiting for

travelers to board. Along the far shore under the imposing Schiedam Gate are river transport boats. By the Rotterdam Gate

to the right lie two herring busses, with which fishermen harvested North Sea herring, undergoing refitting. Above this quiet

moorage is the busy skyline of Delft. The steeple standing in sunlight belongs to the New Church. The red-tiled roofs left

of the Schiedam Gate mark the offices and warehouse of the East India Company, which was responsible for much of what went

into the transport boats moored outside the gate. Barely poking above these roofs, to the left of the conical tower of the

Parrot Brewery, is the steeple of the Old Church, where Vermeer is buried. It was painted in 1660 or 1661.

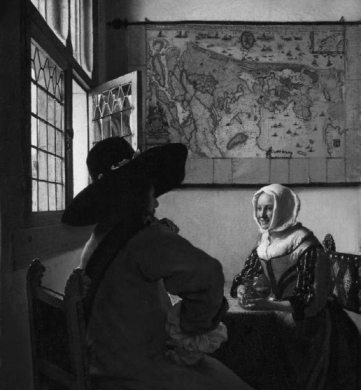

2. JOHANNES VERMEER,

OFFICER AND LAUGHING GIRL

. Mild perspectival distortion imparts visual dynamism to this conversation between the officer in his scarlet tunic and the

young woman. The domestic setting contains many signs of the outside world. The tinted wine glass the young woman cups in

her hands comes, if not from the Murano glassworks in Venice, then from Venetian glassblowers in Antwerp who fled there a

century earlier. The map, printed by Willem Blaeu from Delft plates, depicts the provinces of Holland and West Friesland surrounded

in beige on three sides by the Zuidersee, the Rhine estuary, and the North Sea across the top. Three dozen tiny ships recall

the fleets of Dutch East India Company. Finally, there is the grand hat on the officer’s head, fashioned from felt manufactured

from the fur of beavers trapped in the eastern woodlands of Canada. The painting dates from around 1658.

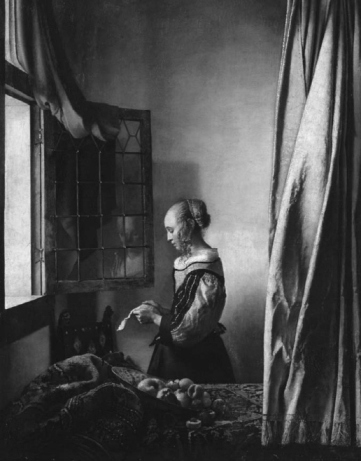

3. JOHANNES VERMEER,

YOUNG WOMAN READING A LETTER AT AN OPEN WINDOW

. This may be the earliest of the many paintings in which Vermeer staged models and things around furniture in his studio.

The letter-reader is probably Catharina, wearing the same dress she will don for

Officer and Laughing Girl

. We see her twice, once in profile and once obliquely reflected in the panes of the open window, and this twofold portrait

doubles the sense of someone wholly absorbed in her reading. Tumbled on the table lie two of the favourite imports of the

era, a Turkish carpet and a Chinese dish. The dish, a piece of blue-and-white export ware from the kiln town of Jingdezhen,

is of a style that was all the rage when Vermeer painted this picture, about 1657. The sunlight on the fruit is Vermeer’s

first use of pointillist technique.

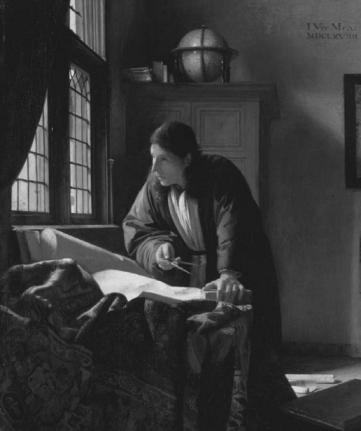

4. JOHANNES VERMEER,

THE GEOGRAPHER

. This is one of a pair of paintings, of a man of learning, probably commissioned by the subject. The other,

The Astronomer

, shares the same theme of the pursuit of knowledge. The model may well be Antony van Leeuwenhoek, draper, surveyor, developer

of the microscope, and a Vermeer family friend. Although the date of 1669 that appears on the wall above Vermeer’s signature

is not original, it may correctly date the painting. The room is littered with signs of the outside world. Another Turkish

carpet fills the foreground, while all around the scholar are spread nautical maps showing the routes that mariners were taking

across the oceans. A sea chart of Europe printed by Willem Blaeu hangs on the back wall, and a globe published by Hendrick

Hondius on his father’s design sits on the wardrobe. The geographer poses as the hero caught in a moment of reflection, striving

to assemble a comprehensive account of the world from the new geographical knowledge pouring into Europe from all over the

globe.

5. A PLATE FROM THE LAMBERT VAN MEERTEN MUSEUM OF DELFT. What looks like a Chinese porcelain plate is neither porcelain nor

Chinese. The plate itself is glazed earthenware, as the chips on the right side of the rim reveal, probably manufactured in

Delft around the end of the seventeenth century. The decorative elements are all faux-Chinese images, which the anonymous

painter has picked up from sources that are now lost. The iconography suggests he was copying from a popular Chinese religious

text. Five monks, one of them smoking a pipe, populate the clouds in the foreground to the left. A magical boy on a unicorn-like

creature appears across from them, and figures looking variously like Daoist deities or Confucian officials walk in the Oriental

garden. On the bridge above them, a slightly crazed-looking man with a crutch tries to capture a crane, the Chinese symbol

of longevity. The plate as a whole offers a delightfully cluttered impression of whimsy, humour, and Oriental bizarrerie.

6. JOHANNES VERMEER,

WOMAN HOLDING A BALANCE

. We do not know whether Vermeer titled this work when he painted it about 1664, but when it was put on auction in Amsterdam

thirty-two years later, it was called

A Young Lady Weighing Gold

. A later collector changed the name to

A Woman Weighing Pearls

, presumably because of the visual prominence of the strings of pearls on the table. In fact, the woman—and, again, the model

was probably Catharina Bolnes—is weighing not pearls or gold, but coins. If the pearls are in the picture, it is because they

were stored in the same box in which this householder keeps her cash, and have to be removed when she lifts out the scales.

And if coins have to be weighed, it is because the Dutch were not as yet using completely standardized coins, and the weight

of the metal mattered. The Flemish painting of the Last Judgment behind her head underscores the act of judging, though she

herself is guilty only of being a good accountant. The sedate yet dynamic composition show Vermeer at the height of his creative

powers.