Vermeer's Hat (20 page)

Authors: Timothy Brook

One way in which they construed their taste for tobacco differently was to treat the compulsion to smoke as a sign of the

true gentleman. Elegant men, declared one elite commentator, “cannot do without it however briefly, and to the end of their

lives never tire of it.” Addiction was not a physical shortcoming, as we like to interpret it, but the sign of a passionate

mind. A gentleman did not smoke just because he liked to; everyone liked to smoke. He did so because his sensitive nature

turned him into a

yanke

, “tobacco’s guest” or “tobacco’s bondservant.” The refined gentleman experienced the desire to smoke as an estimable compulsion,

something that his pure nature could not allow him to do without. It seems to us like an elevated way of explaining nicotine

addiction before that concept was available; but for the Chinese elite it was more than that. It was a marker of social status

deeply embedded in the particular cultural norms of late-imperial China.

Around this sense of compulsion grew up an elite culture of smoking, in praise of which the poets were enlisted. Hundreds

of poems on the subject of tobacco survive from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The noted poet Shen Deqian wrote

an entire cycle of smoking poems, in which he presents smoking as the most refined of pleasures and the most elegant of pastimes,

quite beyond the appreciation of ordinary folk. If they appear in the poems, it is only as servants, never as smokers. Here

he describes his ivory pipe:

Through my pipe I draw the fiery vapour,

From out of my chest I spew white clouds.

The attendant takes away the ash,

Brings wine to amplify the intoxication.

I apply the flame to know the taste,

Letting it burn in the elephant’s tusk.

Smoke in turns presents the poet with an image that allows him to align smoking to clouds and the heavenly realm of Daoist

immortals and even the cosmos, all of which lie far beyond the reach of ordinary human experience. Another poet similarly

associates tobacco smoke with the summoning of souls, like incense before an ancestral tablet:

Soul-summoning fragrance rises from the tobacco:

All over the country all the time the plant is being picked.

I laugh to think that in days of yore people had only ordinary leaves

As I watch a world of smoke and cloud pour out of you.

These poems appear in an anthology of poetry and prose devoted entirely to the theme of smoking. The collection was assembled

in the eighteenth century by Chen Cong, a gentleman of leisure living just west of Shanghai. Chen had a local reputation as

a poet, but

The Tobacco Manual

is the book for which he is best known. Smoking was the great passion of his life, and the only way he can explain this passion

is to suppose an affinity with a past life. He muses that he must have been a Buddhist monk once, and that “my having burned

incense in an earlier life” explains why he is compelled to inhale burning fumes in this life. In his book he anthologizes

the work of prominent poets, like Shen Deqian, but he also includes poems he commissioned his friends to write specially for

the volume. One friend responded to his invitation by describing Chen (“my arriving guest”) coming to his home. Naturally,

politeness demands that he receive his visitor by offering him a smoke:

The tobacco box is casually produced for my arriving guest,

A gentleman who has known all the matters of my heart for a decade.

Poetic blossoms have sprung from his brush since his childhood,

And now

The Tobacco Manual

emerges from our clouds of smoke.

If Chen Cong is smoking’s literary chronicler, Lu Yao is its arbiter of taste. His

Smoking Manual

of 1774 is a documentary of smoking practices as well as a guide explaining how to smoke elegantly. “In recent times there

has not been one gentleman who does not smoke,” Lu declares. “Liquor and food they can dispense with, but tobacco they absolutely

cannot do without.” Since everyone was smoking, it was essential that the well-bred smoker learn not to do it like any common

rustic. Smoking was part of one’s personality, and had to be done in a way that expressed the smoker’s social distinction.

Lu’s passion in his book is thus to align smoking with elegance. To this end, he compiles several lists of good and bad smoking

decorum: when it is appropriate to smoke and when it is taboo, when the smoker should restrain the urge to smoke and when

it can be done without offense. He notes that “even women and children all have a pipe in their hands,” but his instructions

are not for them. They are for his social peers.

Lu dictates certain occasions when it is appropriate to light up: when you have just woken up, after a meal, and when you

are entertaining a guest. He also advocates smoking as a stimulant for writing, as many a contemporary did. “When you are

moistening the ink and licking the brush to compose poetry and just cannot loosen your thoughts, hum in quiet meditation and

inhale some fine tobacco: it cannot help but be of some aid.” There were, however, occasions when it absolutely did not do

to smoke: when listening to string music, for instance, or looking at plum blossoms, or performing a ritual ceremony. He reminded

his readers that smoking was definitely inappropriate when you appeared before the emperor. It was also not to be indulged

in while making love with a “beautiful woman,” by which he meant someone other than your wife.

Lu’s book is also full of practical advice. Don’t smoke while riding a horse. You may stick your tobacco pouch and pipe in

your belt so that you can smoke once you get where you’re going—to forget to bring your own tobacco could put you in an awkward

situation later on—but don’t light up until you dismount. Similarly, while walking on fallen leaves is not a good time to

light up, nor while standing next to a pile of old paper. Lu also offers face-saving tips on decorum. Don’t smoke while coughing

up phlegm or when your breathing rasps. If you keep trying to light your pipe and it doesn’t catch, just put it aside. In

other words, don’t let your smoking create a poor appearance. One final piece of strategic advice is offered for the socially

overburdened. If you have a guest on your hands whom you would rather see depart, don’t bring out the tobacco. He’ll only

linger.

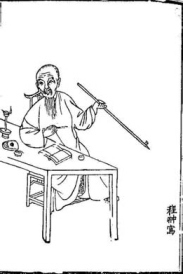

Tobacco enthusiast Chen Cong. From his

Tobacco Manual

, 1805.

THIS ELEGANT HABIT OF REFINED consumption morphed unexpectedly in the nineteenth century into something quite different, and

quite unexpected: opium addiction. The poppy from which opium is refined was, like tobacco, of foreign origin, though it had

long ago been indigenized in China as an expensive medicine used to relieve a range of ailments from constipation and abdominal

cramps to toothache and general debility. It was not something you smoked, however; it was taken in pill or tonic form. By

one report, a considerable amount of opium, under the pleasant name of “hibiscus medicine,” went to the imperial palace in

the later reigns of the Ming dynasty, where it was used for its pharmacopoeic properties and not as a recreational drug. Given

the general understanding that all things ingested affected the well-being of the body, the line between the two was not sharply

drawn.

At the turn of the seventeenth century, the Dutch started bringing opium from India into Southeast Asia, where they sold it

as a mood enhancer, specifically with military applications. It was believed that if opium was given to soldiers, it made

them fearless. In 1605, the VOC was able to use a gift of gunpowder and six pounds of opium to entice the king of Ternate,

one of the smaller Spice Islands boasting a huge output of cloves, into a trading relationship. Both were to use in wars against

his rivals. When Muslims in the southern Philippines were fighting the Spanish in the following decade, it was said that an

assassin dispatched to kill the Spanish commander had rendered himself fearless by taking opium before carrying out his assignment.

The consumption of opium broadened only when it merged with an agent that could deliver the drug in a palatable form, and

that agent was none other than tobacco. Soaking tobacco leaves in a solution derived from the sap of opium poppies produced

a far more potent form of tobacco. This doctored product was called

madak

, and it seems to have been taken up as a more potent version of tobacco rather than as a different drug altogether. The practice

started among Chinese trading with the Dutch on Taiwan, where they briefly maintained a base until 1662. From there it slipped

into China. Chen Cong assumed that it arrived by the same route as tobacco, entering Moon Harbor from Manila, but it is the

Dutch rather than the Spanish who get the credit for the drug’s introduction—yet another strand in Indra’s seventeenth-century

web.

Opium and tobacco had two things in common. They were smoked, and they had come to China from a distant place through foreign

hands. Lu Yao and Chen Cong both decided that this was enough to justify including the subject of opium in their tobacco manuals,

although opium was shifting away from madak form just at this time. By late in the eighteenth century, opium was not smoked

as madak. It was consumed directly by igniting small lumps in a pipe bowl tilted over an oil lamp, then inhaling the smoke

through the stem. The modern opium fix had found its form.

From what Chen Cong was able to learn about opium, the substance was not just a more potent form of tobacco. He makes this

point after quoting at length this anonymous description of opium intoxication as “the realm of perfect happiness”: “How shall

I describe the beauties of opium? Its smell is fragrant, its taste lightly sweet, and it deals well with a dampened spirit

and melancholy thoughts. As soon as I lie down and lean on an armrest to inhale, my spirit revives, my head clears, and my

vision becomes sharper. Then my chest expands and my exaltation doubles. After some time my bones and sinews feel tired and

my eyes want to close. At that moment I plump my pillow and lie in perfect peace without a care in the world”—to which Chen

skeptically replies, “Oh, really?” Lu Yao likewise is suspicious of this potent form of “smoke.” He even revives the specter

of death by smoking, which Chinese tobacco wisdom had set aside a century earlier.

Opium’s “realm of perfect happiness” was a space many Chinese chose to enter during the next great wave of globalization in

the nineteenth century, when English traders brought opium from India to China to reverse the trade deficit that came from

buying so much tea. (They also started building tea plantations in India to reduce the distance and therefore the cost of

transport.) Chinese merchants proved willing to retail this profitable commodity, promoting its distribution throughout the

country. Opium would work its way into all levels of society, just as tobacco had done, forcing a far more troubling transculturation

that still haunts Chinese memories of their past and serves as an enduring symbol of China’s victimization by the West.

Just how successfully opium transculturated into China is illustrated by the following poem, which invokes all the standard

Daoist tropes of tobacco poetry to domesticate the drug. This poem appears in a little booklet called

The Condolence Collection

. The booklet is a collection of verses suitable for sending on the death of a friend. Each verse is crafted to suit a particular

occasion. The poems in the last section have been tagged according to cause of death. The following verse, marked as suitable

for sending on the occasion of a death by opium overdose, shows how thoroughly the taste for opium was lodged in the culture

that received it:

Swallowing dawn mist and drinking sea vapors, he was indifferent [to censure];

Through opium pods and incense, he proved himself immortal before his time.

He may have sealed up his white bones with opium paste,

Yet never he will be without a lamp to illuminate the Yellow Springs

[Hades].

Relying on his opium pipe, he expended great effort to comprehend his fate,

In the midst of fire and smoke, he uttered his

final thoughts.

Mounting a crane and bestriding the wind, where has he now gone?

He has simply followed the tide of smoke, arriving at the Western Heaven.

The romance of opium has long since disappeared. In its turn, the long era of global tobacco smoking is fitfully approaching

an end. But we should remember that our rejection of smoking is quite recent. Back in 1924, tobacco was not something to deplore

or give up.

When the German polymath Berthold Laufer in that year published his pamphlet on the history of tobacco in Asia, he ended it

by praising smoking. “Of all the gifts of nature, tobacco has been the most potent social factor, the most efficient peacemaker,

and greatest benefactor to mankind. It has made the whole world akin and united it into a common bond. Of all luxuries it

is the most democratic and the most universal; it has contributed a large share toward democratizing the world. The very word

has penetrated into all languages of the globe, and is understood everywhere.” Though smokers can today still be counted in

the hundreds of millions worldwide, this sentiment is no longer one we embrace. Pleasure and health now go in different directions.