Vermeer's Hat (23 page)

Authors: Timothy Brook

While the boom lasted, mine owners made incredible fortunes. The phrase “as rich as Potosí” entered the English language.

No one lived in the shadow of the Rich Hill and remained untouched, though whether one did well or badly depended on a complex

array of factors that included ethnic status, social ties, capital, and pure luck. As fortunes were made and lost, violence

did much of the sorting among those who were caught between extreme wealth and extreme poverty: violence between Spaniards

and Indians, between Spanish-born and American-born (known as Creoles), and between ethnic factions, especially between the

Basques, who tended to control the ore refineries, and everyone else. One small incident or affront to honor could throw the

entire city into turmoil. When in 1647 the American-born Mariana de Osorio on her wedding day rejected the Basque to whom

her Andalusian parents betrothed her in favor of a Creole who had been wooing her through the Creole manager of her father’s

refinery, a virtual civil war erupted between Basques and Creoles that dragged on for years.

Potosí did far more than enrich the men who controlled it and pit the rest in deadly struggles against each other. It enriched

Spain first of all, but it also financed the consolidation of the Spanish Empire in South America, funded its reach across

the Pacific to the Philippines, and drew the formerly separate economies of the Americas, Europe, and Asia into a de facto

condominium. This happened without anyone intending that it should. Silver gained a global life of its own, as individuals

improvised in the face of opportunity and compulsion to keep the bullion flowing.

Before the silver could be transported, it had to be coined at the Potosí mint into reals.

1

The greater portion went to Europe by two different routes, the official route and the “back door.” The official route, under

the control of the Spanish crown, ran west over the mountains to the port of Arica on the coast, a journey by pack animal

that took two and a half months. From the coast of Peru it was shipped north to Panama, whence Spanish ships carried it across

the Atlantic to Cadiz, the port serving Seville, the center of the world silver trade. The back door route was technically

illegal but so profitable that it siphoned off as much as a third of Potosí’s silver production. This route went south down

to the Rio de la Plata, the River of Silver, into Argentina, the Land of Silver. It arrived in Buenos Aires, where Portuguese

merchants transported it across the Atlantic to Lisbon. There it was exchanged for commodities that were in demand in Peru,

particularly African slaves. Much of the silver that reached Lisbon and Seville moved quickly to London and Amsterdam, but

it did not tarry for long there. It passed through them and on to its final destination, the place that Europeans would later

call “the tomb of European moneys”: China.

China was the great global destination for European silver for two reasons. First of all, the power of silver to buy gold

in Asian economies was higher than it was in Europe. If twelve units of silver were needed to buy one unit of gold in Europe,

the same amount of gold could be bought for six or less in China. In other words, silver coming from Europe bought twice as

much in China compared to what it could buy in Europe. Adriano de las Cortes makes this point when he describes sixty-eight

ceremonial stone arches spanning the main street of Chaozhou in his record of his year of captivity in China. He expects his

reader to be astonished at the lavishness of this scene, then explains that the cost in silver of building them is much lower

in China than in Spain (“the largest of them did not cost more than two or three thousand pesos”) precisely because the purchasing

power of silver in China is much higher than in Spain. Compound this advantage with generally lower production costs in China,

and the profits to be gained from taking silver to China and buying commodities to sell in Europe were enormous.

The second reason for China’s being the destination for silver was that European merchants had little else to sell in the

China market. With the exception of firearms, European products could not compete with Chinese manufactures in quality or

cost. European manufactures offered little more than novelty. Silver was the one commodity that did compete well with the

native product, for silver was in short supply there. China had silver mines, but the government severely restricted production,

fearing that it could not control the flow of silver from the mines into private hands.

2

It also declined to mint silver coins, restricting coinage to bronze cash in the hope that this would keep prices low. These

measures could do nothing against the economy’s need for silver, however. As that economy grew, the demand for silver grew.

By the sixteenth century, prices in China for anything but the smallest transactions were calibrated by weight of silver,

not by unit of currency—which is why Chinese would immediately have understood what Catharina Bolnes was doing in

Woman Holding a Balance

. Weighing silver was part of everyday economic transactions in China.

The Chinese thirst for silver was so strong that most of the Spanish reals that Dutch merchants brought into the Netherlands

simply went out again in the direction of Asia. The demand was for pure silver, but reals were circulating as something like

an international currency in Southeast Asia, and Chinese merchants were happy to take them. The coins were trusted because

Spanish mints kept their silver content steady at 0.931 fineness, though the ultimate fate of the reals that reached China

was to be melted down. Only when war and embargo strangled the flow of reals to Holland did Dutch governments mint their own

coins. The silver ducat on Catharina’s table was introduced in 1659 to meet just this sort of shortfall.

The Dutch shipped a vast amount of silver to Asia during the seventeenth century. On average, the VOC sent close to a million

guilders’ worth to Asia every year (roughly ten metric tons by weight). That annual volume tripled by the end of the 1690s.

The cumulative value was stunning. In the half century from 1610 through 1660, the headquarters of the VOC authorized the

export of just slightly under fifty million guilders—almost five hundred tons of silver. It is hard even to imagine such a

mountain of silver. Add to this an equivalent volume of silver that the VOC was shipping from Japan to China in the three

decades after 1640, and the mountain of silver grows by at least half as much again.

What did all this silver buy for the Dutch? It paid for commodities unavailable in Europe that sold well in the home market:

chiefly spices in the early years, which were edged aside by textiles later in the seventeenth century, and supplemented by

tea and then coffee in the middle of the eighteenth. Looking into Dutch paintings of the seventeenth century, we see it also

bought beautiful things such as porcelain bowls. One of the puzzles of this trade is that the invoice value of the goods officially

returning in the holds of VOC ships (which of course fails to account for “private” cargo such as the ceramic load of the

White Lion

) was a quarter of the value of the silver going out. This shortfall did not dismay the Company, for the VOC sold what came

back to Europe at prices that amply repaid the original investment. The rest of the silver was used in part to pay for the

huge costs of running the Dutch colonial empire in Southeast Asia, and in larger part to buy commodities that the Company

sold elsewhere within Asia for a profit. The bulk of the silver, in other words, was the capital that the VOC used to buy

its way into the Asian market, stimulating intraregional as well as global trade. Who could have guessed that silver from

Potosí would gain such power—and end up on Catharina’s table?

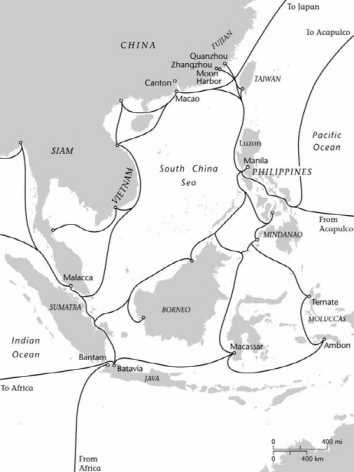

Silver flowed east from Potosí to Europe and then from Europe to Asia, but that was not the only route it took to China, nor

even the most important. Twice the volume of silver that went east also went west, first to the coast and then up to Acapulco,

from where it crossed the Pacific to Manila in the Philippines. At Manila, the silver was traded for Chinese goods and then

shipped to China. A river of silver linked the colonial economy of the Americas with the economy of south China, the metal

extracted on one continent paying for goods manufactured on another for consumption on a third.

The flowing river worked to the advantage of many Spaniards and many Chinese, but not all. Spanish royal officials regularly

complained that “all of this wealth passes into the possession of the Chinese, and is not brought to Spain, to the consequent

loss of the royal duties.” To staunch the flow, King Philip imposed restrictions on the amount of silver that could be sent

across the Pacific. What defeated Philip was the fact that the profit on purchases made in Manila was far higher than the

profit on goods brought from Spain. There was a political imperative to strengthen Spain’s ties across the Atlantic, but there

was an economic imperative driving silver across the Pacific. And so Manila became the nexus where the European economy hooked

up to the Chinese economy: the place where the two hemispheres of the seventeenth-century globe joined.

When the Spanish first arrived in Manila in 1570, they found a trading port there under the control of a Moro rajah named

Soliman. The Moros were a seaborne Muslim trading community that had moved up from the south over the preceding half century,

expanding their control of trading ports throughout insular Southeast Asia. This made them the chief rivals of the Spanish.

The first Spanish commander who went to Manila tricked Soliman into granting him territory at Manila. He used an old ruse,

borrowed from the

Aeneid

, of asking for a piece of land no bigger than an ox hide. As a Chinese writer indignantly reports the story several decades

later, “The Franks tore the ox hide into strips and joined them end to end to a length of a dozen kilometers which they used

to mark out a piece of land, and then insisted that the rajah fulfil his promise. He was surprised but could not go back on

his word as a gentleman and had to grant permission.” Shortly thereafter the Spanish assassinated Soliman and burned the rest

of the Moros out of Manila. The phrase “losing the country for one ox hide” entered the Chinese lexicon as a shorthand for

being swindled by Europeans; it was still in use in the nineteenth century.

TRADE ROUTES AROUND THE SOUTH CHINA SEA

The first Spaniards in Manila found some three hundred Chinese merchants already there, dealing in silk, iron, and porcelain.

Relations started out well, each side sensing that the other might be a profitable trading partner. In fact, the timing was

perfect. For the preceding half century, China had closed its borders to maritime trade in order to discourage the rampant

piracy along the coast, much of it in Japanese hands. Merchants from the southeastern province of Fujian did dare to sail

abroad, following the arc of islands from Taiwan down through the Philippines to the Spice Islands, but they did so at the

risk of execution if caught. The Chinese state had no imperial ambition to follow its merchants’ path, much less support their

adventures. Its ambition was quite the opposite: to prevent the private wealth and corruption that could only come from foreign

trade.

This was the situation until 1567, when a new emperor came to the throne in Beijing and lifted the ban on maritime commerce.

It was a sign that the pressure of foreign demand was having its effect. Overnight, pirates became merchants, contraband goods

became export commodities, and clandestine operations became a business network linking ports of Southeast Asia, including

Manila, to Fujian’s two major commercial cities, Quanzhou and Zhangzhou. Zhangzhou’s port, Moon Harbor, became the main portal

through which the bulk of the commodities going out, and the silver coming in, tied China to the outside world.

If this was an empire, it was an empire purely of trade, not of conquest. The Spanish imagined their future in East Asia rather

differently. Two years after the killing of Soliman, a Spaniard in Manila petitioned the king of Spain for permission to lead

eighty men to China to conquer that country. Philip II (after whom the Philippines had been named while he was still crown

prince) had the good sense not to be persuaded. A second proposal arrived the following year for an invasion force of sixty

men. Three years after that, Francisco Sande, then governor of the Philippines, corrected these estimates and declared that

Spain would need four to six thousand soldiers, plus a supporting Japanese armada, to conquer China. Still, he thought conquest

possible, given his generally contemptuous view of Chinese. They are “a mean, impudent people, as well as very importunate,

” Governor Sande insisted. “Almost all are pirates, when any occasion arises, so that none are faithful to their king. Moreover,

a war could be waged against them because they prohibit people from entering their country. Besides, I do not know, nor have

I heard of, any wickedness that they do not practice; for they are idolaters, sodomites, robbers, and pirates, both by land

and sea.”