Voyage of the Beagle (73 page)

Read Voyage of the Beagle Online

Authors: Charles Darwin

December 26th.

—Mr. Bushby offered to take Mr. Sulivan and myself in his boat some miles up the river to Cawa-Cawa, and proposed afterwards to walk on to the village of Waiomio, where there are some curious rocks. Following one of the arms of the bay we enjoyed a pleasant row, and passed through pretty scenery, until we came to a village, beyond which the boat could not pass. From this place a chief and a party of men volunteered to walk with us to Waiomio, a distance of four miles. The chief was at this time rather notorious from having lately hung one of his wives and a slave for adultery. When one of the missionaries remonstrated with him he seemed surprised, and said he thought he was exactly following the English method. Old Shongi, who happened to be in England during the Queen's trial, expressed great disapprobation at the whole proceeding: he said he had five wives, and he would rather cut off all their heads than be so much troubled about one. Leaving this village, we crossed over to another, seated on a hill-side at a little distance. The daughter of a chief, who was still a heathen, had died there five days before. The hovel in which she had expired had been burnt to the ground: her body, being enclosed between two small canoes, was placed upright on the ground, and protected by an enclosure bearing wooden images of their gods, and the whole was painted bright red, so as to be conspicuous from afar. Her gown was fastened to the coffin, and her hair being cut off was cast at

its foot. The relatives of the family had torn the flesh of their arms, bodies, and faces, so that they were covered with clotted blood; and the old women looked most filthy, disgusting objects. On the following day some of the officers visited this place, and found the women still howling and cutting themselves.

We continued our walk, and soon reached Waiomio. Here there are some singular masses of limestone resembling ruined castles. These rocks have long served for burial places, and in consequence are held too sacred to be approached. One of the young men, however, cried out, "Let us all be brave," and ran on ahead; but when within a hundred yards, the whole party thought better of it, and stopped short. With perfect indifference, however, they allowed us to examine the whole place. At this village we rested some hours, during which time there was a long discussion with Mr. Bushby, concerning the right of sale of certain lands. One old man, who appeared a perfect genealogist, illustrated the successive possessors by bits of stick driven into the ground. Before leaving the houses a little basketful of roasted sweet potatoes was given to each of our party; and we all, according to the custom, carried them away to eat on the road. I noticed that among the women employed in cooking, there was a man-slave: it must be a humiliating thing for a man in this warlike country to be employed in doing that which is considered as the lowest woman's work. Slaves are not allowed to go to war; but this perhaps can hardly be considered as a hardship. I heard of one poor wretch who, during hostilities, ran away to the opposite party; being met by two men, he was immediately seized; but as they could not agree to whom he should belong, each stood over him with a stone hatchet, and seemed determined that the other at least should not take him away alive. The poor man, almost dead with fright, was only saved by the address of a chief's wife. We afterwards enjoyed a pleasant walk back to the boat, but did not reach the ship till late in the evening.

December 30th.

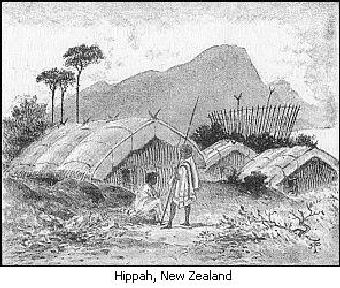

—In the afternoon we stood out of the Bay of Islands, on our course to Sydney. I believe we were all glad to leave New Zealand. It is not a pleasant place

457

Amongst the natives there is absent that charming simplicity which is found in Tahiti; and the greater part of the English are the very refuse of society. Neither is the country itself attractive. I look back but to one bright spot, and that is Waimate, with its Christian inhabitants.

Sydney—Excursion to Bathurst—Aspect of the woods—Party of natives—Gradual extinction of the aborigines—Infection generated by associated men in health—Blue Mountains—View of the grand gulf-like valleys—Their origin and formation—Bathurst, general civility of the lower orders—State of society—Van Diemen's Land—Hobart Town—Aborigines all banished—Mount Wellington—King George's Sound—Cheerless aspect of the country—Bald Head, calcareous casts of branches of trees—Party of natives—Leave Australia.

January 12th, 1836.

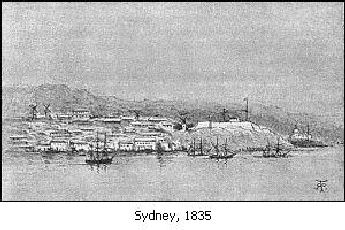

—Early in the morning a light air carried us towards the entrance of Port Jackson. Instead of beholding a verdant country, interspersed with fine houses, a straight line of yellowish cliff brought to our minds the coast of Patagonia. A solitary lighthouse, built of white stone, alone told us that we were near a great and populous city. Having entered the harbour, it appears fine and spacious, with cliff-formed shores of horizontally stratified sandstone. The nearly level country is covered with thin scrubby trees, bespeaking the curse of sterility. Proceeding farther inland, the country improves: beautiful villas and nice cottages are here and there scattered

459

along the beach. In the distance stone houses, two and three stories high, and windmills standing on the edge of a bank, pointed out to us the neighbourhood of the capital of Australia.

At last we anchored within Sydney Cove. We found the little basin occupied by many large ships, and surrounded by warehouses. In the evening I walked through the town, and returned full of admiration at the whole scene. It is a most magnificent testimony to the power of the British nation. Here, in a less promising country, scores of years have done many more times more than an equal number of centuries have effected in South America. My first feeling was to congratulate myself that I was born an Englishman. Upon seeing more of the town afterwards, perhaps my admiration fell a little; but yet it is a fine town. The streets are regular, broad, clean, and kept in excellent order; the houses are of a good size, and the shops well furnished. It may be faithfully compared to the large suburbs which stretch out from London and a few other great towns in England; but not even near London or Birmingham is there an appearance of such rapid growth. The number of large houses and other buildings just finished was truly surprising; nevertheless, every one complained of the high rents and difficulty in procuring a house. Coming from South America, where in the towns every man of property is known, no one thing surprised me more than not being able to ascertain at once to whom this or that carriage belonged.

I hired a man and two horses to take me to Bathurst, a village about one hundred and twenty miles in the interior, and the centre of a great pastoral district. By this means I hoped to gain a general idea of the appearance of the country. On the morning of the 16th (January) I set out on my excursion. The first stage took us to Paramatta, a small country town, next to Sydney in importance. The roads were excellent, and made upon the MacAdam principle, whinstone having been brought for the purpose from the distance of several miles. In all respects there was a close resemblance to England: perhaps the alehouses here were more numerous. The iron gangs, or parties of convicts who have committed here some offence, appeared the least like England: they were working in chains, under the charge of sentries with loaded

460

arms. The power which the government possesses, by means of forced labour, of at once opening good roads throughout the country, has been, I believe, one main cause of the early prosperity of this colony. I slept at night at a very comfortable inn at Emu ferry, thirty-five miles from Sydney, and near the ascent of the Blue Mountains. This line of road is the most frequented, and has been the longest inhabited of any in the colony. The whole land is enclosed with high railings, for the farmers have not succeeded in rearing hedges. There are many substantial houses and good cottages scattered about; but although considerable pieces of land are under cultivation, the greater part yet remains as when first discovered.

The extreme uniformity of the vegetation is the most remarkable feature in the landscape of the greater part of New South Wales. Everywhere we have an open woodland, the ground being partially covered with a very thin pasture, with little appearance of verdure. The trees nearly all belong to one family, and mostly have their leaves placed in a vertical, instead of as in Europe, in a nearly horizontal position: the foliage is scanty, and of a peculiar pale green tint, without any gloss. Hence the woods appear light and shadowless: this, although a loss of comfort to the traveller under the scorching rays of summer, is of importance to the farmer, as it allows grass to grow where it otherwise would not. The leaves are not shed periodically: this character appears common to the entire southern hemisphere, namely, South America, Australia, and the Cape of Good Hope. The inhabitants of this hemisphere, and of the intertropical regions, thus lose perhaps one of the most glorious, though to our eyes common, spectacles in the world—the first bursting into full foliage of the leafless tree. They may, however, say that we pay dearly for this by having the land covered with mere naked skeletons for so many months. This is too true; but our senses thus acquire a keen relish for the exquisite green of the spring, which the eyes of those living within the tropics, sated during the long year with the gorgeous productions of those glowing climates, can never experience. The greater number of the trees, with the exception of some of the Blue-gums, do not attain a large size; but they grow tall and tolerably straight, and stand well apart. The bark of some of the Eucalypti falls annually, or

461

hangs dead in long shreds which swing about with the wind, and give to the woods a desolate and untidy appearance. I cannot imagine a more complete contrast, in every respect, than between the forests of Valdivia or Chiloe, and the woods of Australia.

At sunset, a party of a score of the black aborigines passed by, each carrying, in their accustomed manner, a bundle of spears and other weapons. By giving a leading young man a shilling, they were easily detained, and threw their spears for my amusement. They were all partly clothed, and several could speak a little English: their countenances were good-humoured and pleasant, and they appeared far from being such utterly degraded beings as they have usually been represented. In their own arts they are admirable. A cap being fixed at thirty yards distance, they transfixed it with a spear, delivered by the throwing-stick with the rapidity of an arrow from the bow of a practised archer. In tracking animals or men they show most wonderful sagacity; and I heard of several of their remarks which manifested considerable acuteness. They will not, however, cultivate the ground, or build houses and remain stationary, or even take the trouble of tending a flock of sheep when given to them. On the whole they appear to me to stand some few degrees higher in the scale of civilisation than the Fuegians.

It is very curious thus to see in the midst of a civilised people, a set of harmless savages wandering about without knowing where they shall sleep at night, and gaining their livelihood by hunting in the woods. As the white man has travelled onwards, he has spread over the country belonging to several tribes. These, although thus enclosed by one common people, keep up their ancient distinctions, and sometimes go to war with each other. In an engagement which took place lately, the two parties most singularly chose the centre of the village of Bathurst for the field of battle. This was of service to the defeated side, for the runaway warriors took refuge in the barracks.

The number of aborigines is rapidly decreasing. In my whole ride, with the exception of some boys brought up by Englishmen, I saw only one other party. This decrease, no doubt, must be partly owing to the introduction of spirits, to

462

European diseases (even the milder ones of which, such as the measles,

1

prove very destructive), and to the gradual extinction of the wild animals. It is said that numbers of their children invariably perish in very early infancy from the effects of their wandering life; and as the difficulty of procuring food increases, so must their wandering habits increase; and hence the population, without any apparent deaths from famine, is repressed in a manner extremely sudden compared to what happens in civilised countries, where the father, though in adding to his labour he may injure himself, does not destroy his offspring.