Welcome to Your Child's Brain: How the Mind Grows From Conception to College (21 page)

Read Welcome to Your Child's Brain: How the Mind Grows From Conception to College Online

Authors: Sandra Aamodt,Sam Wang

Tags: #Pediatrics, #Science, #Medical, #General, #Child Development, #Family & Relationships

Learned preferences for food accumulate over the first few years of life. A liking for salt emerges by age two, and eventually for more complex flavors such as cherries. This process starts before birth. Indeed, preferences for the foods of one’s own culture may be transmitted through mother’s milk and even in the womb.

Flavor preferences learned in infancy can last for years.

The womb is a flavorful environment. Fetuses swallow cupfuls of amniotic fluid per day, and the fluid can reach their olfactory epithelia. As we have said, at birth, newborns have a pronounced preference for the flavor of amniotic fluid (especially their own) over water. Amniotic fluid can also carry traces from the mother’s diet. To test for flavor conditioning in utero, researchers had pregnant women drink about ten ounces (thirty centiliters) of carrot juice every other day for three weeks during the third trimester. Their babies were less likely to make faces when given carrot-flavored cereal for the first time—and more likely to eat it.

Flavor learning in utero has been shown in other species of mammals, not just humans. Rabbit pups show an increased preference for juniper berry flavor after prior exposure to this taste in their mother’s milk or in the mother’s diet during gestation, or even if they are housed with juniper-scented fecal pellets. Pups seem to have multiple ways of learning about what might be okay to eat. It’s at least possible that some distinctive aspects of sushi flavors, such as fish and seaweed, could have reached Sam’s daughter before birth or in infancy.

PRACTICAL TIP: WORRIED ABOUT YOUR CHILD’S WEIGHT?

As a parent, it’s normal to be concerned about what your child eats, but anxiety about childhood obesity is usually neither necessary nor helpful for most children. Parents need to be careful that the solution they choose doesn’t end up causing more harm than the problem.

Because they’re growing, children need more calories than adults per pound of body weight. Young children also need to eat a lot more fat than adults do. The National Institutes of Health recommends that children under two should get 50 percent of their calories from fat, and children older than two should get 25–35 percent of calories from fat. Dietary fat is an essential contributor to early brain development. Food restriction is tricky in children: low-calorie diets may prevent them from growing properly, and low-fat diets are associated with inadequate intake of important nutrients. Complicating things further, it’s difficult to be certain how much a child should weigh at a given age because kids often put on some extra fat in preparation for a growth spurt.

Given these difficulties, how do you decide how much food your child should be eating? In most cases, if you provide a variety of healthy foods and opportunities for regular exercise, you can trust your child’s brain to manage food intake correctly. (This approach probably will not work as well if you have a lot of junk food in the house.) The brain’s weight-regulation system is extremely complicated, including more than twenty molecules that increase eating and a similar number that decrease eating, based on a variety of nutritional cues. The brain will do its best job of balancing food intake with energy use if children are simply allowed to eat when they are hungry and stop when they are full. This approach also helps them learn to regulate their own eating as adults without binging or starving.

Growing up in a weight-obsessed culture is particularly difficult for girls. Healthy puberty requires the addition of body fat, in the form of breasts and hips, at just the age when girls are particularly sensitive to body image problems (see

chapter 8

). Eating disorders affect more than one in a hundred young women between fifteen and twenty-four years of age. (There is roughly one man with an eating disorder for every eight women.) In one longitudinal study, teenage girls who reported dieting repeatedly or being teased about their weight by family members were much more likely than average to have developed an eating disorder or to have become overweight (from a normal starting weight) five years later, suggesting that strict parental efforts to control their daughters’ weight were typically ineffective—or even counterproductive. Girls who reported eating regular family meals in a pleasant atmosphere were less likely than average to develop an eating disorder or become overweight.

Taste preferences can also arise indirectly. For instance, four-month-old infants are less likely to make faces when presented with salty water if their mothers experienced early pregnancy nausea. We don’t know for certain why morning sickness would lead to a liking for salt. One possibility is that sick mothers become dehydrated or depleted of sodium, leading to the secretion of the signaling molecules

renin

and

angiotensin

, which cause a desire for salt in adults. (Renin is an enzyme, secreted by the kidney, that participates in regulating blood pressure; angiotensin is a

peptide

that causes blood vessels to constrict.)

Considerable information about flavors is also transferred through mother’s milk. One aspect of children’s experience is simple familiarity, leading to tolerance. If a lactating mother consumes garlic oil or carrot juice, babies are less likely to react, either positively or negatively, when the same flavoring is added to a bottle.

Flavor preferences learned in infancy can last for years. To illustrate, let’s look at an experiment that focused on baby formula, which comes in several varieties based on milk, soy, and protein hydrolysate (for babies with allergies to milk and soy). Nonmilk formulas are notably sour and bitter, and the hydrolysate formulas are particularly nasty. (Try one sometime.) Generally, just consuming a food multiple times is sufficient to reduce negative reactions. Furthermore, infant taste is particularly malleable during the first few months. In this experiment, children who were fed soy or hydrolysate formula before the age of one still chose to drink it at age four or five over milk-based formula (as opposed to milk-reared

kids, who refused soy- and hydrolysate-based formulas and made yucky faces). Soy- and hydrolysate-fed kids were considerably more tolerant of sour or bitter flavors added to apple juice. They also were more positive about other bitter foods—including broccoli.

As children become more verbal, they acquire additional ways of learning about flavors and smells. In both children and adults, perception and liking can be influenced by a word label. For example, adult subjects gave a more pleasant smell rating when they rated a container labeled

cheddar cheese

compared with a container labeled

body odor

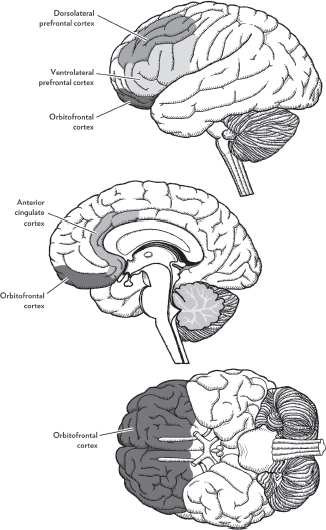

even though the containers emitted the same odor. When the adults’ brains were scanned, activity was changed in the

rostral anterior cingulate

cortex, the

medial

orbitofrontal cortex, and the amygdala. These regions receive information from both smell and taste pathways and appear to be places for making mental associations with flavors. As children grow, they learn to make associations between foods and complex contexts, including social value, as adults do. Pleasure can be a force for good in your child’s development, an idea that we explore in the next section.

PART FOUR

THE SERIOUS BUSINESS OF PLAY

THE BEST GIFT YOU CAN GIVE: SELF-CONTROL

PLAYING FOR KEEPS

MOVING THE BODY AND BRAIN ALONG

ELECTRONIC ENTERTAINMENT AND THE

MULTITASKING MYTH

Chapter 13

THE BEST GIFT YOU CAN GIVE: SELF-CONTROL

AGES: TWO YEARS TO SEVEN YEARS

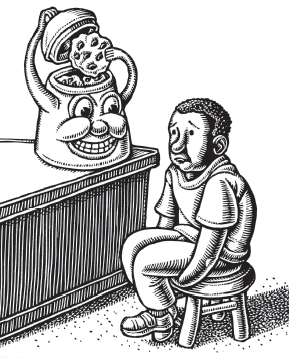

At the age of three or four, resisting temptation is always a visible struggle. Finding a good strategy is a key element to success—and the good news for parents is that strategies can be taught. Indeed, learning self-control strategies at an early age can pay off for years afterward.

Young children’s play contributes to the development of their most important basic brain function: the ability to control their own behavior in order to reach a goal. This capacity underlies success in many areas that parents care about, from socialization to schoolwork. The neural circuits that are responsible for it are some of the latest-developing parts of the brain, as any parent of a two-year-old can tell you. But even at this age, you can detect and encourage an early stage of their mental growth, the inhibition of behavioral impulses.

Preschool children’s ability to resist temptation is a much better predictor of eventual academic success than their IQ scores. The classic test for this ability, devised by psychologists, is to put a marshmallow on the table and tell the child that she can have two marshmallows if she can wait a few minutes without eating the first one. Alternatively, she can ring a bell at any time to bring the researcher back into the room and get just one marshmallow. The average delay time is about six minutes for a four-year-old. A child who can hold out fifteen minutes at that age is doing exceptionally well and definitely deserves both marshmallows without further delay.

More than a decade later, those preschool delay times correlate strongly with adolescent SAT scores—predicting about a quarter of the variation among individuals in one study. Delay times in preschool also correlate with the ability to cope with stress and frustration in adolescence, as well as the ability to concentrate. Other tests of the ability to inhibit behavior for delayed gratification correlate with math and reading skills early in elementary school, which makes sense considering that learning academic subjects requires concentration and persistence.

As it improves with age, self-control continues to predict academic success. In a study of eighth graders, self-discipline at the beginning of the school year—measured in part by the students’ ability to carry a dollar for a week without spending it in order to earn another dollar—predicts grades, school attendance, and standardized achievement test scores at the end of the year. The students’ self-control ability accounted for twice as much of the variation among individuals on all these measures as their IQ scores.