Welcome to Your Child's Brain: How the Mind Grows From Conception to College (24 page)

Read Welcome to Your Child's Brain: How the Mind Grows From Conception to College Online

Authors: Sandra Aamodt,Sam Wang

Tags: #Pediatrics, #Science, #Medical, #General, #Child Development, #Family & Relationships

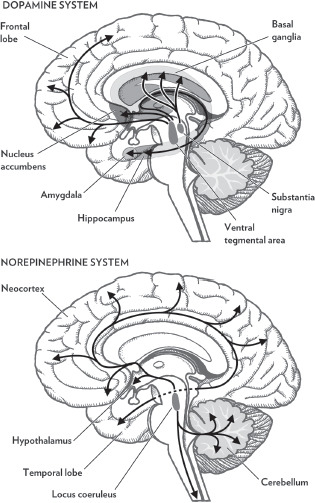

The brain generates chemical signals that encode a key component of fun:

reward

, the quality that makes us come back for more. Reward is conveyed within the brain by dopamine, a neurotransmitter that has many functions depending on where and when it is secreted. Dopamine is made by cells in the brain’s core, in the

substantia nigra

and

ventral tegmental area

(see figure above). In rats, dopamine and play are linked. Among chemicals that activate receptors for various neurotransmitters, only a few increase play behavior, including drugs that activate dopamine receptors.

One way to find out what play is good for is to take it away from animals and see how they fare. The problem is that this experiment is nearly impossible to do. Animals (including children) are irrepressible; they play under the most adverse of conditions. The only way to get an animal to stop playing is to restrain its mobility. This severe restriction leads to decreases in physical activity and increases in stress, as measured by the amount of the stress hormone cortisol in saliva. Play, exercise, and stress are closely linked.

Play is necessary for forming normal social connections.

Though the deprivation experiment is hard to do, that very fact means that seeing an animal play already tells us something good about its state. In young squirrel monkeys, lower levels of cortisol are associated with high amounts of play, suggesting either that play reduces stress, or possibly that unstressed monkeys are more likely to play. In bear cubs during their first year of life, survival over the winter is highly correlated with the amount that cubs played during the preceding summer. This suggests that play might be an indicator of health or resistance to stress. No matter how you slice it, seeing your child play is a good sign.

Play activates other brain signaling systems as well, including the neurotransmitter norepinephrine (see figure opposite). Its close relative epinephrine (also known as adrenaline) is released to the body as a fast component of stress-related signaling (see

chapter 26

). As the main activator of the sympathetic nervous system, epinephrine mobilizes our energies for “fight, flight, or fright,” as the medical-school mnemonic goes. Norepinephrine too is involved in rousing us to attention and action, but by acting as a neurotransmitter.

Norepinephrine also facilitates learning mechanisms at synapses. In some neurons, norepinephrine improves brain plasticity, so that change becomes possible when this chemical is present in elevated amounts. The same is true for dopamine, which accounts for how reward leads to long-term changes to make us want more—brains are rewired when reward occurs.

Though real-life stressors trigger the release of both epinephrine and cortisol, play does not increase cortisol. This hormone helps us in genuinely dangerous situations by shutting down functions that are dispensable for a little while, such as learning of experiences that are not immediately related to the stressful context (see

chapter 26

). It is safe to say that if you find play to be a source of stress, you’re

not doing it right. Even violent video games, which raise physiological arousal as measured by epinephrine-based response, do not increase cortisol. In some cases, cortisol levels actually decrease—people work off stress by shooting ’em up. On the whole, play is associated with responses that facilitate learning.

Risk taking in children’s play may be an important developmental process. It tests boundaries and establishes what is safe and what is dangerous.

The conditions of play—the generation of signals that enhance learning without an accompanying stress response—allow the brain to explore possibilities and learn from them. In other words, a major function of play may well be to provide practice for real life. As we’ve written before, the use of a skill or other mental capacity builds up that ability. Evidence from animals suggests that this is the case for play, which usually reflects an animal’s more serious needs. Kittens play at pouncing on things, a behavior that resembles the hunting they do later. Fawns don’t pounce much, but they do gambol around, a behavior that resembles escape.

So it’s possible that play is practice that prepares animals for the real activity later—when it matters. For example, in

chapter 13

we described Tools of the Mind, a preschool program that uses complex play to get children to make elaborate plans and exercise self-restraint—practice for the prefrontal cortex and self-control. Even before that the kindergarten movement, which in the nineteenth century popularized the concept of preschool education, was based on the idea that songs, games, and other activities were a means for children to gain perceptual, cognitive, social, and emotional knowledge that would prepare them for entering the world.

In mammals, play is necessary for forming normal social connections. Rats and cats that are raised in social isolation become incompetent in dealing with others of their kind, typically reacting with aggression. In our species, dysfunction in adults is often presaged by abnormal play as children. A notable feature of psychopaths is that their childhoods were lacking in play. Serial killers are often reported to have had abnormal play habits, keeping to themselves or engaging in

notably cruel forms of play. Sometimes such problems are associated with early-life head injury. (Needless to say, abnormal play does not necessarily mean that you are raising a serial killer.)

Culture is also transmitted through play. Middle-class mothers in the U.S. encourage their infants to pay attention to objects and are likely to prompt them to play with toys such as blocks. In contrast, Japanese mothers encourage their babies to engage in social interactions while playing, for example, by suggesting that they feed or bow to their dolls. Communities that emphasize the development of independence place more importance on object play, while interdependent communities encourage social play.

There are some downsides to play, too. For one thing, though play is defined as occurring in the absence of stressors or external threats, children aren’t always good at detecting threats, so play can be dangerous. People are not alone in having this problem. In a study of baby seal mortality, twenty-two of twenty-six deaths resulted from the pups playing outside the sight or sound of their parents. Play can distract people and other animals from recognizing danger.

But even here, play may be practice for real life. Risk taking in children’s play may be an important developmental process. It tests boundaries and establishes what is safe and what is dangerous. In the U.S., playground equipment has been made very safe, leading to the unanticipated problem that children lack experience with such boundaries, which may lead to trouble later in life.

In addition to providing experience, play also helps children learn what they like and don’t like. The Nobel chemistry laureate Roger Tsien tells of reading about exotic chemical reactions before he was eight years old, then trying out the reactions for himself. He was able to get beautiful color changes to happen in his house or backyard. Because he didn’t have enough laboratory glassware, he had to make equipment from used milk jugs and empty Hawaiian Punch cans (see

photo

).

After he grew up, Roger won the Nobel Prize for developing colored dyes and proteins that become brighter or change hue when they encounter chemical signals in living cells, including neurons. (This can make certain biological processes, such as brain signaling, much easier to see and understand.) The invention of tools to visualize what is happening in active biological systems, Roger’s great contribution to science, had its roots in that childhood interest in home chemistry experiments. Not all childhood experiments lead to such heights, of course, but

no matter what your children’s eventual interests may be, discovering them may be one of the most important outcomes of play.

Think of it this way: play is the work of children. It is perhaps the most effective way for them to learn life skills and to find out what they like. For these reasons, it is important to prevent play from becoming a compulsory, dreary activity, as its enjoyable nature is part of what makes most children grow like dandelions. So, rather than trying to change your child’s personality through enforced activities (which is tough anyway; see

chapter 17

), let her play, and help her become who she’s going to be.

A homemade chemistry apparatus built by later Nobel laureate Roger Tsien when he was about fourteen years old. He was trying to synthesize aspirin

.

Chapter 15

MOVING THE BODY AND BRAIN ALONG

AGES: FOUR YEARS TO EIGHTEEN YEARS

It’s obvious that your child is using her brain when she’s reading, but you may not realize that her brain is also getting a workout when she plays soccer. Sports and exercise in childhood are beneficial to motor control and cognitive ability—and, perhaps most important, they set up habits that can keep your child’s brain healthy into old age. For all these reasons, the recent trend to reduce or eliminate physical education in U.S. schools is likely to be bad news for children.

The control of movement and balance continues to improve throughout childhood. During this time, the brain gets better at coordinating its commands to various muscles and interpreting feedback from sensory systems. Skills like walking over rough ground may feel effortless to you, but your brain is working very hard to produce that impression. Controlling the body is a tough job, and it requires practice. Computer experts have found it surprisingly difficult to make a robot that can play sports or even walk steadily. The instructions are complicated.

Physical activity in children is correlated with a number of positive characteristics. Physical education programs that emphasize enjoyment over competition or criticism are most successful at producing all these benefits. Active children have higher self-esteem than inactive children. Feelings of stress, depression, and anxiety are less common in active than in inactive children. Some of these results may occur because depressed children are reluctant to exercise. But on the other

hand, a few small intervention studies show that exercise modestly reduces anxiety and depression symptoms in children, as it clearly does in adults. Although parents sometimes worry that physical activity will take up time better devoted to academic effort, no study has shown a drop in academic performance as a consequence of increased activity. A few studies have even shown that fitness is associated with higher achievement test scores in children.

Parents should take advantage of these active years to introduce their children to sports that can become lifelong hobbies.

Indeed, a considerable body of research shows that exercise is vital for cognitive ability. Across the lifespan, heart health is brain health. In childhood, aerobic fitness is correlated with math and reading achievement, while muscle strength and flexibility are not. In a meta-analysis, children (ages four to eighteen) who were more physically active tended to score higher on tests of IQ, perceptual skills, verbal ability, mathematical ability, and academic readiness (with an effect size, d’, of 0.32; see

figure

). The relationship was strongest from ages four to seven and from eleven to thirteen. Fit children perform better on attention and conflict cue tasks (

see

), both of which are associated with self-control ability. Fitness also improves performance on a

relational memory task

, remembering which pairs of pictures were shown together, which requires both the prefrontal cortex and the hippocampus.