Welcome to Your Child's Brain: How the Mind Grows From Conception to College (23 page)

Read Welcome to Your Child's Brain: How the Mind Grows From Conception to College Online

Authors: Sandra Aamodt,Sam Wang

Tags: #Pediatrics, #Science, #Medical, #General, #Child Development, #Family & Relationships

This plasticity in adulthood strongly suggests that children should also be able to increase their self-control abilities through experience. In young children, warm supportive mothering is associated with improved self-control ability, even when the mother’s genetic contribution is factored out. During elementary school, computer-based attention training can increase reasoning abilities, and children with the poorest attention before training show the most benefit.

Structured play with other children can also improve executive function. One

promising preschool program uses play to improve self-control in children from disadvantaged backgrounds (see

Practical tip: Imaginary friends, real skills

). All these forms of training probably improve performance of the brain network involved in cognitive control.

You can help by encouraging your child to exercise as much self-control as possible in the context of enjoyable experiences like playing board games. The rules of the game require your child to resist such impulses as moving his piece when it’s not his turn. If you stand over your child and manage every step of the process, you’re depriving him of the experience that will allow him to learn how to organize his own actions. On the other hand, if your child consistently fails to control himself, the game may be too difficult for his developmental stage. Succeeding at challenging self-control tasks builds more success, but repeated failure may instead teach the child that there’s no point in trying.

Children who fail to develop an age-appropriate level of self-control can end up with troubles that multiply. In school, they are likely to get poor grades because they have difficulty concentrating and completing assignments. In addition, parents, teachers, and other students are likely to find them difficult to handle. Because punishment is more likely to induce resentment than to increase self-control (see

chapter 29

), its repetition can eventually establish the poorly self-regulated child as the “bad” or “rebellious” member of the class or of the family. This image, in the eyes of teachers, parents, peers, and the child, can outlast the original problem and contribute to a downward spiral into poor performance and delinquency.

Even young children can benefit from spending time directing their own activities, particularly if they are engaging in imaginative play, alone or with other children. Parents can help by encouraging children to pursue their own interests and enthusiasms. Some children are captivated by producing music, while others would rather build a castle. It probably doesn’t matter exactly what excites your children; as long as they are intensely engaged by an activity and concentrate on it, they will be improving their ability to self-regulate and thus their prospects for the future. Play has many benefits for children, as we will explore in the next chapter.

AGES: TWO YEARS TO EIGHTEEN YEARS

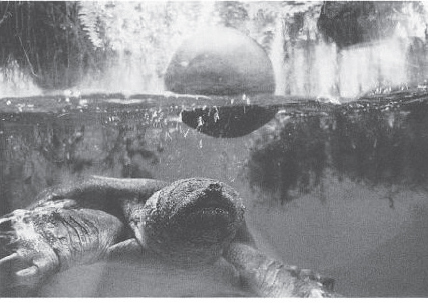

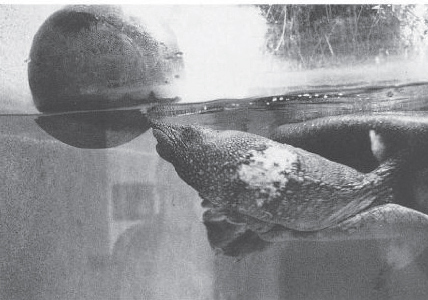

For Pigface, life at the zoo had recently improved. Previously prone to clawing and biting himself, he had been given sticks and other items, with which he developed various tricks. One was to push a basketball with his snout and sometimes snap at it. Hoops of hose were favorite objects, which he would nose and chew and sometimes swim through. On days when his tank was being cleaned, he would get in front of the stream of incoming water and remain there unmoving, just feeling the water run over his face. Once the refilling was done, he was off again. These activities make Pigface sound like an otter or a seal. Movies of him certainly look like such frolicking—except in very slow motion. The behaviors only look like mammalian play when played back at three times normal speed, because Pigface is a turtle (see

photos

).

Similarities run deep between how we and other animals play. When you watch your children play, you may think it’s cute—but they are also learning to match their capacities to future life needs. Object play such as pushing a truck or ball around resembles later activities such as wielding a hammer, hunting, or building machinery. Indeed, play can also take a distinctly animal-like quality. Babies and toddlers like to chew and pull things apart. Biting is a common nuisance in preschool centers—and it’s also practice for the kinds of predation that our species once depended on for food.

Play is widespread among animals, beyond the familiar cases, mammals and birds, to vertebrates and even invertebrates. How can we be sure that an animal is playing? Researchers use three criteria. First, play resembles a serious behavior, such as hunting or escaping, but is done by a young animal or is exaggerated, awkward, or otherwise altered. Second, play has no immediate survival purpose. It appears to be done for its own sake and is voluntary or pleasurable. Third, play occurs when an animal is not under stress and does not have something more pressing to do.

These criteria for play are met by leaping needlefish, water-frolicking alligators, and lizards. At the National Zoo in Washington, D.C., monitor lizards play games of keep-away. The largest monitor species, the Komodo “dragon” lizard, plays tug-of-war with its keepers over a plastic ring. It can pick a familiar keeper’s pockets of notebooks and other objects, then walk around carrying them in its mouth. A movie of a playing Komodo dragon looks quite a bit like play with a dog, only slowed down to about half speed.

The behavior is not just displaced foraging or hunting. If the ring is coated in tasty linseed oil or animal blood, playfulness vanishes and is replaced by a pronounced possessiveness. YouTube videos of Komodo dragons swallowing whole pigs—or even other Komodo dragons—suggest that these food-oriented behaviors are not easily confused with play.

The fact that play is so widespread suggests that it arose long ago in the history of animals. It appears in many animals with far less social complexity than people. This universality suggests that even though play is literally fun and games, it must serve some vital function. In other words, when your child is playing, he is doing something crucial for his development. Furthermore, the features of his play are distinctive not only to him but to humans in general.

Play takes different forms in different animals, including humans. Its content provides some hint as to what it might be good for. Play researchers (there’s a fun-sounding job) recognize three major types of play. Most common is

object play

; that’s what Pigface does with basketballs and hoops. Object play is typically found in species that hunt, scavenge, or eat widely. About as common is

locomotor play

, such as leaping about for no apparent reason. (The term

locomotor

has to do with coordinated movement through space, such as crawling, walking, or running.) Locomotor play is common among animals that move around a lot, for instance, those that swim, fly, or live in trees—and notably, often must get away from predators. The third and most sophisticated form of play is

social play

. Social play can take many forms, including mock fighting, chasing one another, and wrestling. Pretending is a major component of social play.

Social play is especially prominent in animals that show a lot of behavioral flexibility or plasticity. (And of course the most flexible, plastic young animal of all is your child.) In mammals and birds, this boils down to a simple rule: if your species has a big brain for its body size, you probably engage in social play. Among these species, most of the variation in brain size occurs in the forebrain; different mammals or birds of a given body size will have about the same amount of brainstem, but very different amounts of neocortex (in mammals) or forebrain (in birds). Animals with more neocortex or forebrain typically live in larger groups and have more complex social relations. Ducks engage in “coordinated loafing,” in which they basically just hang around together. Great apes and their relatives (such as humans) form societies in which alliances are constantly shifting, and in which the young play recognizable games, such as chasing, wrestling, and tickling. In doing these things, your child is indulging her inner ape.

DID YOU KNOW? PLAY IN ADULT LIFE

In many people, play continues in adulthood and is a major contributor to problem solving. Physical scientists often report having built and taken apart machines when they were kids. Sam did this too, with activities such as building a sundial in elementary school.

Conversely, work in adult life is often most effective when it resembles play. Indeed, total immersion in an activity is often the mark that an activity is intensely enjoyable—the concept of

flow

, or what athletes call

being in the zone

.

Flow occurs during active experiences that require concentration but are also highly practiced, where the goals and boundaries are clear but leave room for creativity. It is most likely when your abilities are just sufficient to meet the challenge, in tasks that are neither easy nor impossible. This describes many adult hobbies, from skiing to music, as well as careers like surgery or computer programming. Such immersion can make solving a great challenge as easy as child’s play. Encouraging your child to pursue tasks that produce flow is a great way to contribute to his lifelong happiness.

This phenomenon is not limited to vertebrates. Among invertebrates, perhaps the most complex brains are found in cephalopods, which include squid and octopus. Octopuses use their water jets to push floating objects like pill bottles back and forth in a tank or in a circular path. Despite this behavioral complexity, octopus brains are still small by vertebrate standards—half the diameter of a dime, smaller than those of even the smallest mammals. Another invertebrate that appears to play is the honeybee, which has one of the largest and most

complex nervous systems among invertebrates. As a counterexample, playlike behavior is not reported in houseflies.

Now, maybe play isn’t “for” anything. Perhaps play behavior is simply early maturation, precocious behavior that develops before it is absolutely required. Another possibility is that play is what our brains do when there are no more pressing matters—a screensaver for the mind, as it were.

But these ideas are contradicted by one key piece of evidence: play is fun. At first, this may seem like an odd argument. Aren’t fun activities the ones we engage in for their own sake? Superficially, yes, but dig a little deeper. The enjoyment of an activity is a survival trait. We are wired to like activities that are helpful for our survival. For example, we may think we seek sex because it’s fun, but in reality, sex is essential. Sex is fun because seeking it is adaptive. People who don’t like sex have a harder time finding mates and having kids. In general, enjoying an activity is a hardwired response that causes our brain to seek out that activity. If these essential behaviors weren’t enjoyable, we might forget to do them, and then we wouldn’t make it through life very well. On these grounds, it seems that play must have an adaptive purpose, providing some survival advantage.