What If? (19 page)

Authors: Randall Munroe

Common Cold

Q.

If everyone on the planet stayed away from each other for a couple of weeks, wouldn’t the common cold be wiped out?

— Sarah Ewart

A.

Would it be worth

it?

Th

e common cold is caused by a variety of viruses,

1

but rhinoviruses are the most common culprit.

2

Th

ese viruses take over the cells in your nose and throat and use them to produce more viruses. After a few

days, your immune system notices and destroys it,

3

but not before you infect, on average, one other person.

4

After you fight off the infection, you are immune to that particular rhinovirus strain

—

an immunity that lasts for years.

If Sarah put us all in quarantine, the cold viruses we carry would have no fresh hosts to run to. Could our immune systems then wipe out every copy of the virus?

Before we answer that question, let’s consider the practical consequences of this kind of quarantine.

Th

e world’s total annual economic output is in the neighborhood of $80 trillion, which suggests that interrupting

all economic activity for a few weeks would cost many trillions of dollars.

Th

e shock to the system from the worldwide “pause” could easily cause a global economic collapse.

Th

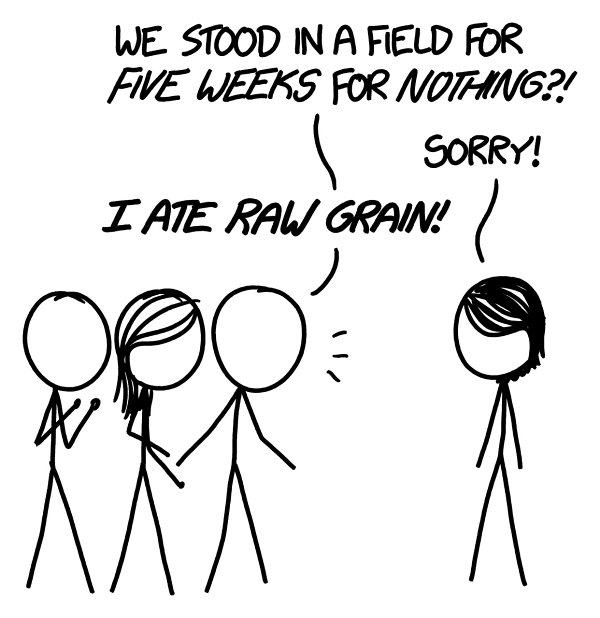

e world’s total food reserves are probably large enough to cover us for four or five weeks of quarantine, but the food would have to be evenly parceled out beforehand. Frankly, I’m not sure what I’d do with a 20-day grain reserve while standing alone in a field somewhere.

A global quarantine brings us to another question: How far apart can we actually

get

from one another?

Th

e world is big,

[

citation needed

]

but there are a lot of people.

[

citation needed

]

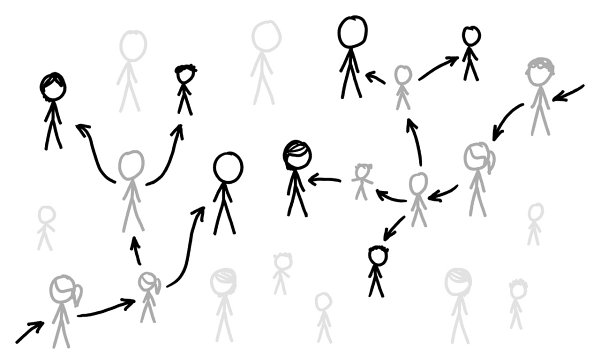

If we divide up the world’s land area evenly, there’s enough room for each of us to have a little over 2 hectares each, with the nearest person 77 meters away.

While 77 meters is probably enough separation to block the transmission of rhinoviruses, that separation would come at a cost. Much of the world’s land is not pleasant to stand around on for five weeks. A lot of us would be stuck standing in the Sahara Desert,

5

or central Antarctica.

6

A more practical

—

though not necessarily cheaper

—

solution would be to give everyone biohazard

suits.

Th

at way, we could walk around and interact, even allowing some normal economic activity to continue:

But let’s set aside the practicality and address Sarah’s actual question: Would it

work

?

To help figure out the answer, I talked to Professor Ian M. Mackay, a virology expert from the Australian Infectious Diseases Research Centre at the University of Queensland.

7

Dr. Mackay said that this idea is actually somewhat reasonable, from a purely biological point of view. He

said that rhinoviruses

—

and other RNA respiratory viruses

—

are completely eliminated from the body by the immune system; they do not linger after infection. Furthermore, we don’t seem to pass any rhinoviruses back and forth with animals, which means there are no other species that can serve as reservoirs of our colds. If rhinoviruses don’t have enough humans to move between, they die out.

We’ve

actually seen this viral extinction in action in isolated populations.

Th

e remote islands of St. Kilda, far to the northwest of Scotland, for centuries hosted a population of about 100 people.

Th

e islands were visited by only a few boats a year, and suffered from an unusual syndrome called the

cnatan-na-gall,

or “stranger’s cough.” For several centuries, the cough swept the island like clockwork

every time a new boat arrived.

Th

e exact cause of the outbreaks is unknown,

8

but rhinoviruses were probably responsible for many of them. Every time a boat visited, it would introduce new strains of virus.

Th

ese strains would sweep the islands, infecting virtually everyone. After several weeks, all the residents would have fresh immunity to those strains, and with nowhere to go, the viruses

would die out.

Th

e same viral clearing would likely happen in any small and isolated population

—

for example, shipwreck survivors.

If all humans were isolated from one another, the St. Kilda scenario would play out on a species-wide scale. After a week or two, our colds would run their course, and healthy immune systems would have plenty of time to clear the viruses.

Unfortunately, there’s one catch, and it’s enough to unravel the whole plan: We don’t all

have

healthy immune systems.

In most people, rhinoviruses are fully cleared from the body within about ten days.

Th

e story is different for those with severely weakened immune systems. In transplant patients, for example, whose immune systems have been artificially suppressed, common infections

—

including rhinoviruses

—

can linger for weeks, months, or conceivably years.

Th

is small group of immunocompromised

people would serve as safe havens for rhinoviruses.

Th

e hope of eradicating them is slim; they would need to survive in only a few hosts in order to sweep out and retake the world.

In addition to probably causing the collapse of civilization, Sarah’s plan wouldn’t eradicate rhinoviruses.

9

However, this might be for the best!

While colds are no fun, their absence might be worse. In his

book

A Planet of Viruses,

author Carl Zimmer says that children who aren’t exposed to rhinoviruses have more immune disorders as adults. It’s possible that these mild infections serve to train and calibrate our immune systems.

On the other hand, colds suck. And in addition to being unpleasant, some research says infections by these viruses also

weaken

our immune systems directly and can open

us up to further infections.

All in all, I wouldn’t stand in the middle of a desert for five weeks to rid myself of colds forever. But if they ever come up with a rhinovirus vaccine, I’ll be first in line.