What If? (17 page)

Authors: Randall Munroe

An ant’s brain might contain a quarter of a million neurons, and thousands of synapses per neuron, which suggests that the world’s ant brains have a combined complexity similar to that of the world’s human

brains.

So we shouldn’t worry too much about when computers will catch up with us in complexity. After all, we’ve caught up to ants, and

they

don’t seem too concerned. Sure, we seem like we’ve taken over the planet, but if I had to bet on which one of us would still be around in a million years

—

primates, computers, or ants

—

I know who I’d pick.

- 1

Except Red Delicious apples, whose misleading name is a travesty.

- 2

Our house had a lot of vases when I was a kid.

- 3

Yet.

- 4

Th

is figure comes from a list (

http://www.frc.ri.cmu.edu/users/hpm/book97/ch3/processor.list.txt

) in Hans Moravec’s book

Robot: Mere Machine to Transcendent

Mind

.

- 5

Although even this might not capture everything that’s going on. Biology is tricky.

- 6

Using 82,944 processors with about 750 million transistors each,

K

spent 40 minutes simulating one second of brain activity in a brain with 1 percent of the number of connections as a human’s.

- 7

If it’s past the year

2036 right now while you’re reading this, hello from the distant past! I hope things are better in the future. P.S. Please figure out a way to come get us.

- 8

“TPA.”

Little Planet

Q.

If an asteroid was very small but supermassive, could you really live on it like the Little Prince?

—Samantha Harper

“Did you eat my rose?” “Maybe.”

A.

Th

e Little Prince

, by

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, is a story about a traveler from a distant asteroid. It’s simple and sad and poignant and memorable.

1

It’s ostensibly a children’s book, but it’s hard to pin down who the intended audience is. In any case, it certainly

has

found an audience; it’s among the best-selling books in history.

It was written in 1942.

Th

at’s an interesting time to write about asteroids, because in 1942 we didn’t actually know what asteroids

looked

like. Even in our best telescopes, the largest asteroids were visible only as points of light. In fact, that’s where their name comes from

—

the word

asteroid

means “starlike.”

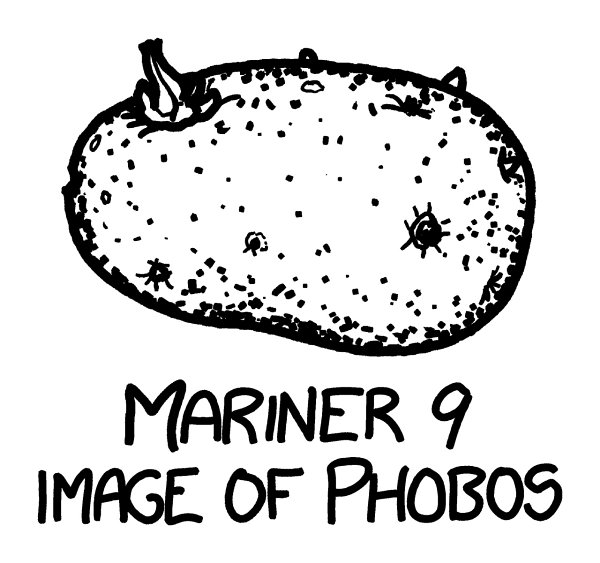

We got our first confirmation of what asteroids looked like in

1971, when

Mariner 9

visited Mars and snapped pictures of Phobos and Deimos.

Th

ese moons, believed to be captured asteroids, solidified the modern image of asteroids as cratered potatoes.

Before the 1970s, it was common for science fiction to assume small asteroids would be round, like planets.

Th

e Little Prince

took this a step further, imagining an asteroid as a tiny planet with gravity, air, and a rose.

Th

ere’s no point in trying to critique the science here, because (1) it’s not a story about asteroids, and (2) it opens with a parable about how foolish adults

are for looking at everything too literally.

Rather than using science to chip away at the story, let’s see what strange new pieces it can add. If there really were a superdense asteroid with enough surface gravity to walk around on, it would have some pretty remarkable properties.

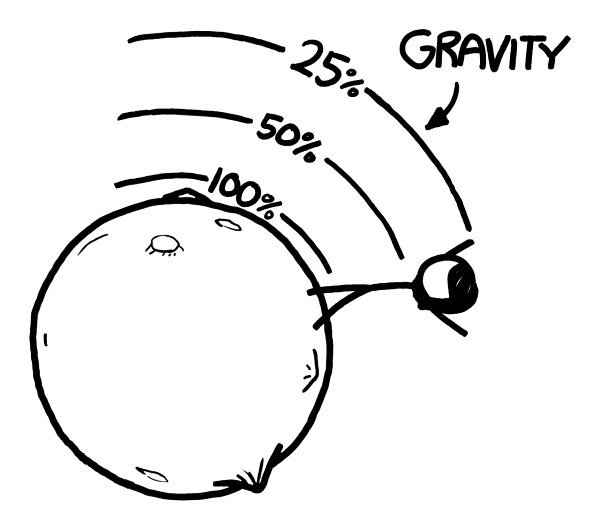

If the asteroid had a radius of 1.75 meters, then in order to have Earthlike gravity at the surface, it would

need to have a mass of about 500 million tons.

Th

is is roughly equal to the combined mass of every human on Earth.

If you stood on the surface, you’d experience tidal forces. Your feet would feel heavier than your head, which you’d feel as a gentle stretching sensation. It would feel like you were stretched out on a curved rubber ball, or were lying on a merry-go-round with your head near

the center.

Th

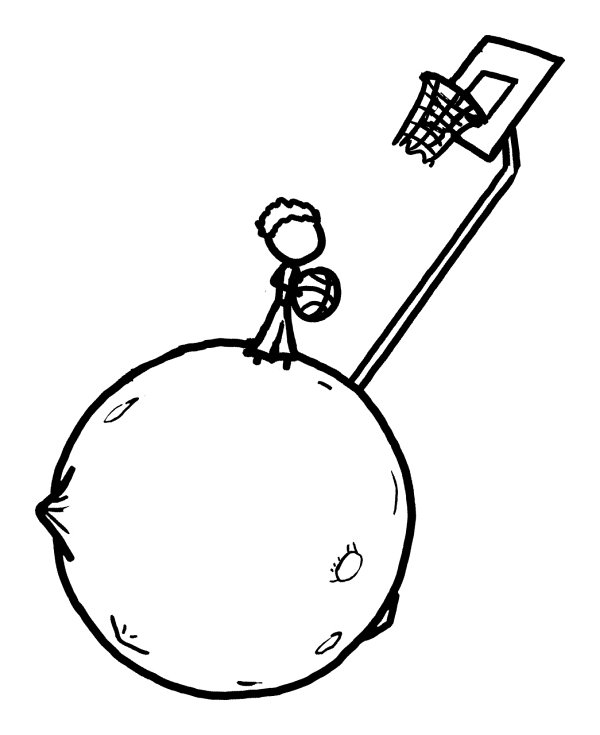

e escape velocity at the surface would be about 5 meters per second.

Th

at’s slower than a sprint, but still pretty fast. As a rule of thumb, if you can’t dunk a basketball, you wouldn’t be able to escape this asteroid by jumping.

However, the weird thing about escape velocity is that it doesn’t matter which direction you’re going.

2

If you go faster than the escape speed, as long as you don’t actually go

toward

the planet, you’ll escape.

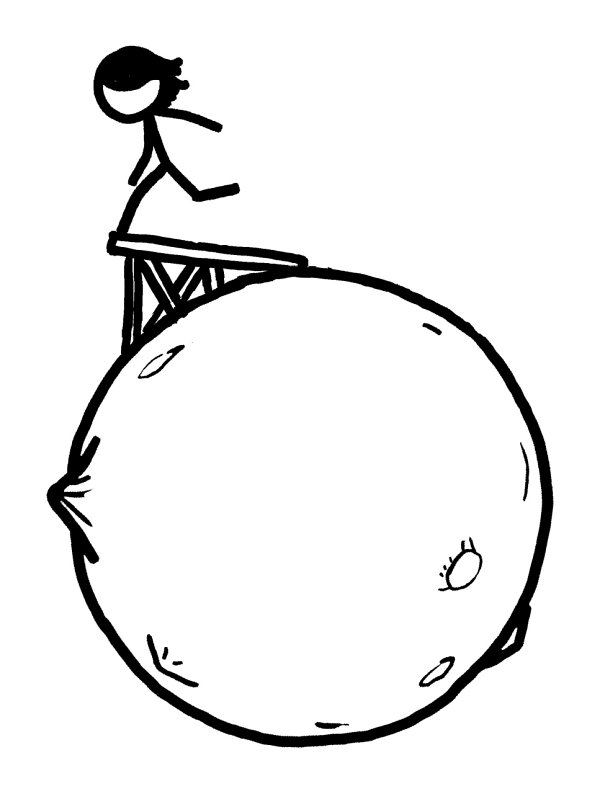

Th

at means you might be able to leave our asteroid by running horizontally and jumping off the end of a ramp.

If you didn’t go fast enough to escape the planet, you’d go into orbit around it. Your orbital speed would be roughly 3 meters per second, which is a typical jogging speed.

But this would be a

weird

orbit.

Tidal forces would act on you in several ways. If you stretched your arm down toward the planet, it would be pulled much harder than the rest of you. And when you reach down with one arm, the rest of you gets pushed upward, which means other parts of your body feel even

less

gravity. Effectively, every part of your body would be trying to go

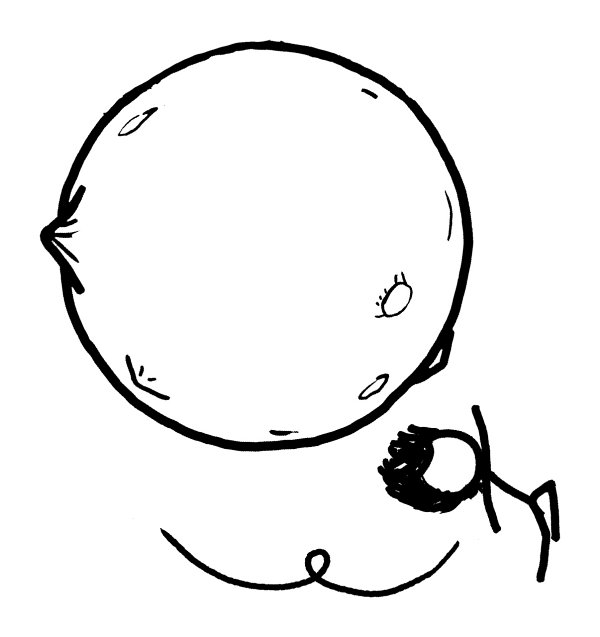

in a different orbit.

A large orbiting object under these kinds of tidal forces

—

say, a moon

—

will generally break apart into rings.

3

Th

is wouldn’t happen to you. However, your orbit would become chaotic and unstable.

Th

ese types of orbits were investigated in a paper by Radu D. Rugescu and Daniele Mortari.

Th

eir simulations showed that large, elongated objects follow strange paths around

their central bodies. Even their centers of mass don’t move in the traditional ellipses; some adopt pentagonal orbits, while others tumble chaotically and crash into the planet.

Th

is type of analysis could actually have practical applications.

Th

ere have been various proposals over the years to use long, whirling tethers to move cargo in and out of gravity wells

—

a sort of free-floating space

elevator. Such tethers could transport cargo to and from the surface of the Moon, or to pick up spacecraft from the edge of the Earth’s atmosphere.

Th

e inherent instability of many tether orbits poses a challenge for such a project.

As for the residents of our superdense asteroid, they’d have to be careful; if they ran too fast, they’d be in serious danger of entering orbit, going into a tumble

and losing their lunch.

Fortunately, vertical jumps would be fine.

Cleveland-area fans of French children’s literature were disappointed by the Prince’s decision to sign with the Miami Heat.

- 1

Although not everyone sees it this way. Mallory Ortberg, writing on the-toast.net, characterized the story of

Th

e Little Prince

as a wealthy child demanding that a plane crash survivor draw him pictures, then critiquing his drawing

style.

- 2

. . . which is why it should really be called “escape speed”

—

the fact that it has no direction (which is the distinction between “speed” and “velocity”) is unexpectedly significant here.

- 3

Th

is is presumably what happened to Sonic the Hedgehog.