What If? (34 page)

Authors: Randall Munroe

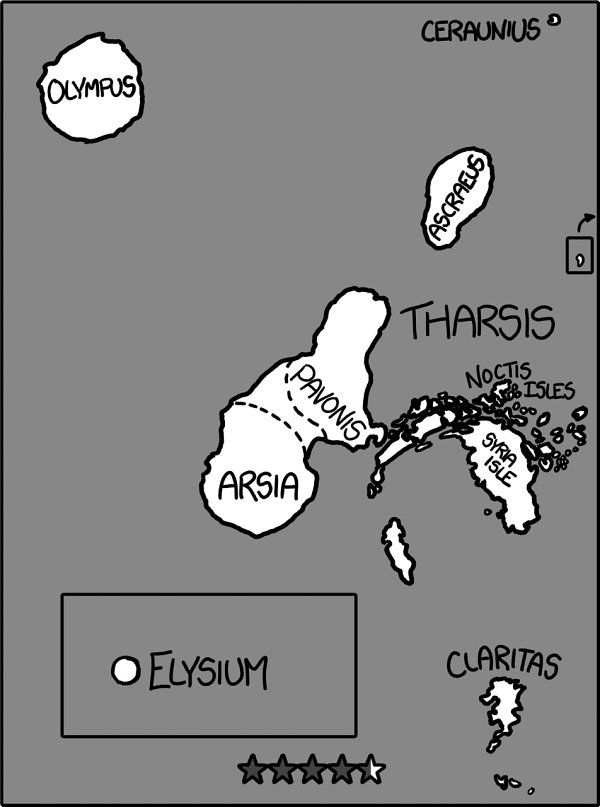

As the water spreads across the surface in earnest, the map splits into several large islands (and innumerable smaller ones).

Th

e water quickly finishes covering most of the high plateaus, leaving only a few islands left.

And then, at last, the flow stops; the oceans back on Earth are drained.

Let’s take a closer look at the main islands:

No rovers remain above water.

Olympus Mons, and a few other volcanoes, remain above water. Surprisingly, they aren’t even

close

to being covered. Olympus Mons still rises well over 10 kilometers above the new sea level. Mars has some

huge

mountains.

Th

ose crazy islands are the result of water filling in Noctis Labyrinthus (the Labyrinth of the Night), a bizarre set of canyons

whose origin is still a mystery.

Th

e oceans on Mars wouldn’t last.

Th

ere might be some transient greenhouse warming, but in the end, Mars is just too cold. Eventually, the oceans will freeze over, become covered with dust, and gradually migrate to the permafrost at the poles.

However, it would take a long time, and until it did, Mars would be a much more interesting place.

When you

consider that there’s a ready-made portal system to allow transit between the two planets, the consequences are inevitable:

Twitter

Q.

How many unique English tweets are possible? How long would it take for the population of the world to read them all out loud?

—Eric H, Hopatcong, NJ

High up in the North in the land called Svithjod, there stands a rock. It is a hundred miles high and a hundred miles wide. Once every thousand years a little bird comes to this rock to sharpen its beak. When the rock has

thus been worn away, then a single day of eternity will have gone by.

—

Hendrik Willem Van Loon

A.

Tweets are 140 characters

long.

Th

ere are 26 letters in English—27 if you include spaces. Using that alphabet, there are 27

140

≈ 10

200

possible strings.

But Twitter doesn’t limit you to those characters. You have all of Unicode to play with, which has room for over a million different

characters.

Th

e way Twitter counts Unicode characters is complicated, but the number of possible strings could be as high as 10

800

.

Of course, almost all of them would be meaningless jumbles of characters from a dozen different languages. Even if you’re limited to the 26 English letters, the strings would be full of meaningless jumbles like “ptikobj.” Eric’s question was about tweets that

actually say something in English. How many of those are possible?

Th

is is a tough question. Your first impulse might be to allow only English words.

Th

en you could further restrict it to grammatically valid sentences.

But it gets tricky. For example, “Hi, I’m Mxyztplk” is a grammatically valid sentence if your name happens to be Mxyztplk. (Come to think of it, it’s just as grammatically

valid if you’re lying.) Clearly, it doesn’t make sense to count every string that starts with “Hi, I’m . . . ” as a separate sentence. To a normal English speaker, “Hi, I’m Mxyztplk” is basically indistinguishable from “Hi, I’m Mxzkqklt,” and shouldn’t both count. But “Hi, I’m xPoKeFaNx” is definitely recognizably different from the first two, even though “xPoKeFaNx” isn’t an English word by any

stretch of the imagination.

Our way of measuring distinctiveness seems to be falling apart. Fortunately, there’s a better approach.

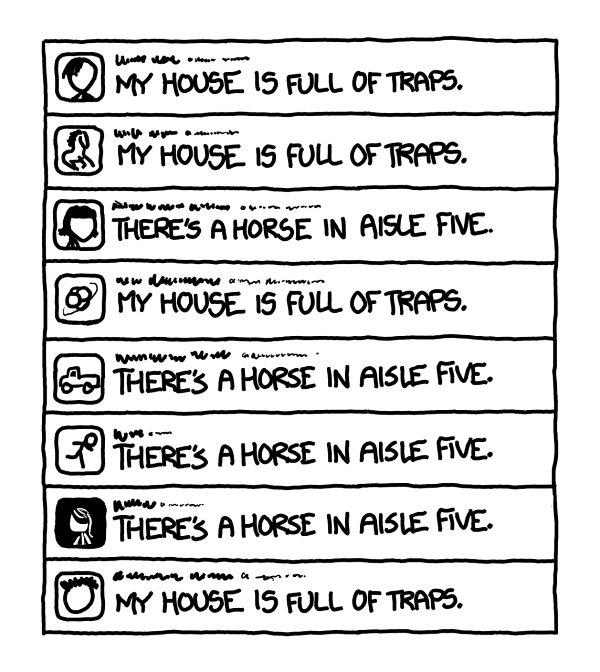

Let’s imagine a language that has only two valid sentences, and every tweet must be one of the two sentences.

Th

ey are:

- “

Th

ere’s a horse in aisle five.” - “My house is full of traps.”

Twitter would look like this:

Th

e messages are relatively long, but there’s not a lot of information in each one

—

all they tell you is whether the person decided to send the trap message or the horse message. It’s effectively a 1 or a 0. Although there are a lot of letters, for a reader who knows the pattern of the language, each tweet carries only one

bit

of information per sentence.

Th

is example hints

at a very deep idea, which is that information is fundamentally tied to the recipient’s uncertainty about the message’s content and his or her ability to predict it in advance.

1

Claude Shannon

—

who almost singlehandedly invented modern information theory

—

had a clever method for measuring the information content of a language. He showed groups of people samples of typical written English that

were cut off at a random point, then asked them to guess which letter came next.

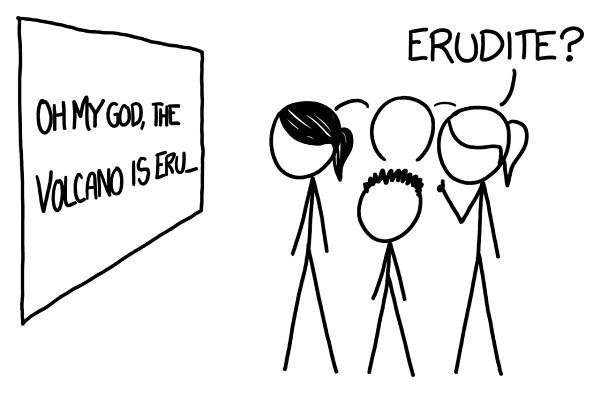

It’s threatening to flood our town with information!

Based on the rates of correct guesses

—

and rigorous mathematical analysis

—

Shannon determined that the information content of typical written English was 1.0 to 1.2 bits per letter.

Th

is means that a good compression algorithm should be able to compress

ASCII

English text

—

which is 8 bits per letter

—

to about ⅛

th

of its original

size. Indeed, if you use a good file compressor on a .txt ebook, that’s about what you’ll find.

If a piece of text contains

n

bits of information, in a sense it means that there are 2

n

different messages it can convey.

Th

ere’s a bit of mathematical juggling here (involving, among other things, the length of the message and something called “unicity distance”), but the bottom line is that it

suggests there are on the order of about 2

140

×

1.1

≈ 2 × 10

46

meaningfully different English tweets, rather than 10

200

or 10

800

.

Now, how long would it take the world to read them all out?

Reading 2 × 10

46

tweets would take a person nearly 10

47

seconds. It’s such a staggeringly large number of tweets that it hardly matters whether it’s one person reading or a billion

—

they won’t be able

to make a meaningful dent in the list in the lifetime of the Earth.

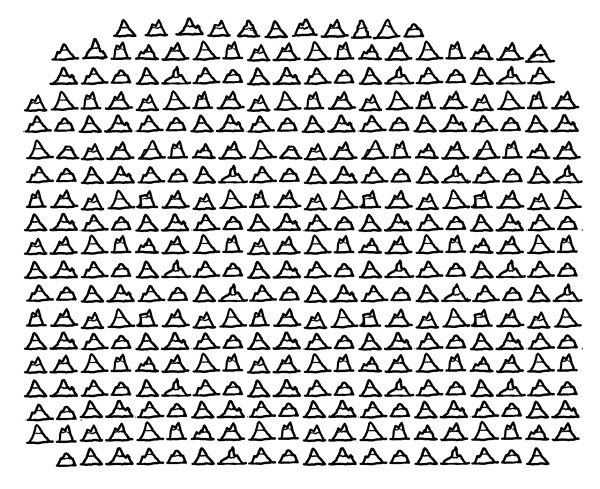

Instead, let’s think back to that bird sharpening its beak on the mountaintop. Suppose that the bird scrapes off a tiny bit of rock from the mountain when it visits every thousand years, and it carries away those few dozen dust particles when it leaves. (A normal bird would probably

deposit

more beak material on the mountaintop

than it would wear away, but virtually nothing else about this scenario is normal either, so we’ll just go with it.)

Let’s say you read tweets aloud for 16 hours a day, every day. And behind you, every thousand years, the bird arrives and scrapes off a few invisible specks of dust from the top of the hundred-mile mountain with its beak.

When the mountain is worn flat to the ground, that’s

the first day of eternity.

Th

e mountain reappears and the cycle starts again for another eternal day: 365 eternal days

—

each one 10

32

years long

—

makes an eternal year.

A hundred eternal years, in which the bird grinds away 36,500 mountains, make an eternal century.

But a century isn’t enough. Nor a millennium.

Reading all the tweets takes you

ten thousand

eternal years.

Th

at’s enough time to watch all of human history unfold, from the invention of writing to the present, with each day lasting as long as it takes for the bird to wear down a mountain.

While 140 characters may not seem like a lot, we will

never

run out of things to say.

- 1

It also hints at a very shallow idea about there being a horse in aisle five.