What If? (39 page)

Authors: Randall Munroe

Sunless Earth

Q.

What would happen to the Earth if the Sun suddenly switched off?

—Many, many readers

A.

Th

is is probably the

single most popular submission to

What If

.

Part of why I haven’t answered it is that it’s been answered already. A Google search for “what if the Sun went out” turns up a lot of excellent articles thoroughly analyzing the situation.

However, the rate

of submission of this question continues to rise, so I’ve decided to do my best to answer it.

If the Sun went out . . .

We won’t worry about exactly how it happens. We’ll just assume we figured out a way to fast-forward the Sun through its evolution so that it becomes a cold, inert sphere. What would the consequences be for us here on Earth?

Let’s look at a few . . .

Reduced risk of solar flares:

In 1859, a massive solar flare and geomagnetic storm hit the Earth. Magnetic storms induce electric

currents in wires. Unfortunately for us, by 1859 we had wrapped the Earth in telegraph wires.

Th

e storm caused powerful currents in those wires, knocking out communications and in some cases causing telegraph equipment to catch fire.

Since 1859, we’ve wrapped the Earth in a lot more wires. If the 1859 storm hit us today, the Department of Homeland Security estimates the economic damage to

the US alone would be several trillion dollars

—

more than every hurricane that has ever hit the US

combined

. If the Sun went out, this threat would be eliminated.

Improved satellite service:

When a communications satellite passes in front of the Sun, the Sun can drown out the satellite’s radio signal, causing an interruption in service. Deactivating the Sun would solve this problem.

Better

astronomy:

Without the Sun, ground-based observatories would be able to operate around the clock.

Th

e cooler air would create less atmospheric noise, which would reduce the load on adaptive optics systems and allow for sharper images.

Stable dust:

Without sunlight, there would be no Poynting–Robertson drag, which means we would finally be able to place dust into a stable orbit around the Sun

without the orbits decaying. I’m not sure whether anyone wants to do that, but you never know.

Reduced infrastructure costs:

Th

e Department of Transportation estimates that it would cost $20 billion per year over the next 20 years to repair and maintain all US bridges. Most US bridges are over water; without the Sun, we could save money by simply driving on a strip of asphalt laid across the

ice.

Cheaper trade:

Time zones make trade more expensive; it’s harder to do business with someone if their office hours don’t overlap with yours. If the Sun went out, it would eliminate the need for time zones, allowing us to switch to UTC and give a boost to the global economy.

Safer children:

According to the North Dakota Department of Health, babies younger than six months should be

kept out of direct sunlight. Without sunlight, our children would be safer.

Safer combat pilots:

Many people sneeze when exposed to bright sunlight.

Th

e reasons for this reflex are unknown, and it may pose a danger to fighter pilots during flight. If the Sun went dark, it would mitigate this danger to our pilots.

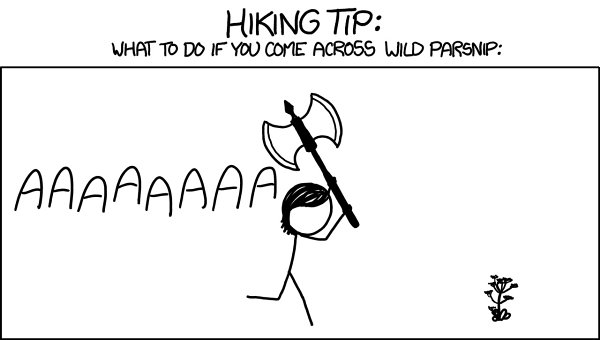

Safer parsnip:

Wild parsnip is a surprisingly nasty plant. Its leaves contain

chemicals called furocoumarins, which can be absorbed by human skin without causing symptoms . . . at first. However, when the skin is then exposed to sunlight (even days or weeks later), the furocoumarins cause a nasty chemical burn.

Th

is is called phytophotodermatitis. A darkened Sun would liberate us from the parsnip threat.

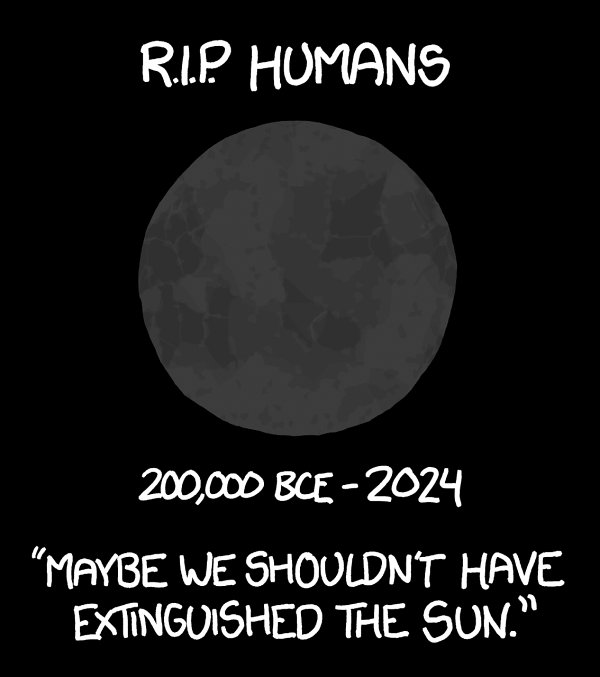

In conclusion, if the Sun went out, we would see a variety of benefits across many areas of our lives.

Are there any downsides to this scenario?

We would all freeze and die.

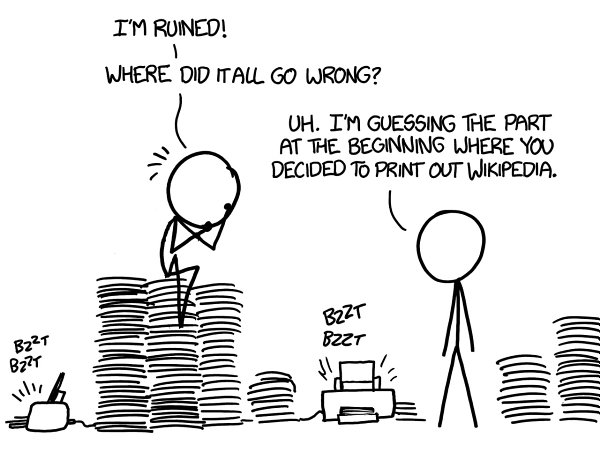

Updating a Printed Wikipedia

Q.

If you had a printed version of the whole of (say, the English) Wikipedia, how many printers would you need in order to keep up with the changes made to the live version?

—Marein Könings

A.

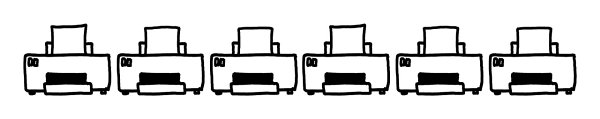

Th

is many.

If a date took you home and you saw a row of working printers set up in his or her living room, what would you think?

Th

at’s surprisingly few printers! But before you try to create a live-updating paper Wikipedia, let’s look at what those printers would be

doing

. . . and how much they’d cost.

Printing Wikipedia

People have considered printing out Wikipedia before.

One student, Rob Matthews, printed every Wikipedia featured article, creating a book several feet thick.

Of course, that’s just a small slice of the best of Wikipedia; the entire encyclopedia would be a lot bigger. Wikipedia user

Tompw

has set up a tool that calculates the current size of the whole English Wikipedia in printed volumes. It would fill a lot of bookshelves.

Keeping up with

the edits would be hard.

Keeping up

Th

e English Wikipedia currently receives about 125,000 to 150,000 edits each day, or 90–100 per minute.

We could try to define a way to measure the “word count” of the average edit, but that’s hard bordering on impossible. Fortunately, we don’t need to

—

we can just estimate that each change is going to require us to reprint a page somewhere. Many

edits will actually change multiple pages

—

but many other edits are reverts, which would let us put back pages we’ve already printed.

1

One page per edit seems like a reasonable middle ground.

For a mix of photos, tables, and text typical of Wikipedia, a good inkjet printer might put out 15 pages per minute.

Th

at means you’d need only about six printers running at any given time to keep pace

with the edits.

Th

e paper would stack up quickly. Using Rob Matthews’ book as a starting point, I did my own back-of-the-envelope estimate for the size of the current English Wikipedia. Based on the average length of featured articles vs. all articles, I came up with an estimate of 300 cubic meters for a printout of the whole thing in plain text form.

By comparison, if you were trying

to keep up with the edits, you’d print out 300 cubic meters every

month

.

$500,000 per month

Six printers isn’t that many, but they’d be running all the time. And that gets expensive.

Th

e electricity to run them would be cheap

—

a few dollars a day.

Th

e paper would be about 1 cent per sheet, which means you’ll be spending about a thousand dollars a day on paper. You’d need to hire

people to manage the printers 24/7, but that would actually cost less than the paper.

Even the printers themselves wouldn’t be too expensive, despite the terrifyingly fast replacement cycle.

But the

ink

cartridges would be a nightmare.

Ink

A study by QualityLogic found that for a typical inkjet printer, the real-life cost of ink ran from 5 cents per page for black-and-white to

around 30 cents per page for photos.

Th

at means you’d be spending four to five figures per

day

on ink cartridges.

You definitely want to invest in a laser printer. Otherwise, in just a month or two, this project could end up costing you half a million dollars:

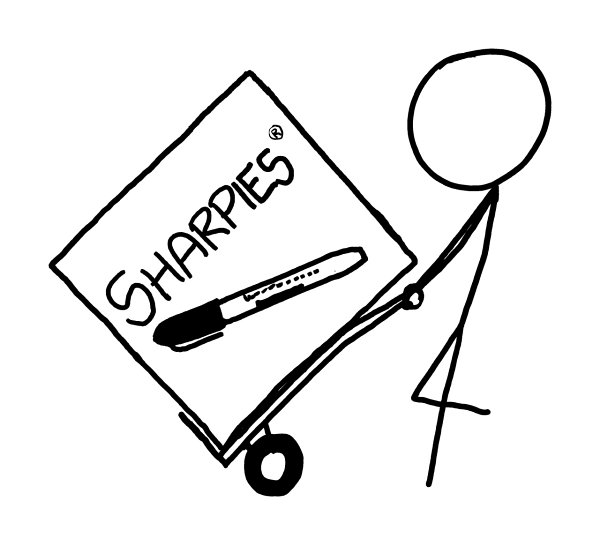

But that’s not even the worst part.

On January 18, 2012, Wikipedia blacked out all its pages to protest proposed Internet-freedom-limiting laws. If, someday, Wikipedia decides to go dark again, and you want to join the protest

. . .

. . . you’ll have to get a crate of markers and color every page solid black yourself.

I would definitely stick to digital.

- 1

Th

e filing system that would be required for this would be mind-bending. I’m fighting the urge to start trying to design it.