What Technology Wants (27 page)

Read What Technology Wants Online

Authors: Kevin Kelly

The past 10,000 years of technology influence the preordained march of technology in each new era. The initial conditions of an embryonic electrical system, for example, can guide the character of its eventual network in several ways. The engineers might choose alternating current (AC), favoring centralization, or direct current (DC), favoring decentralization. Or the system could be installed in 12 volts (by amateurs) or 250 volts (by professionals). The legal regime could favor patent protection or not, and the business models could be built around profits or charitable nonprofit. These initial specifications affected how the internet developed on top of the electric network. All these variables bend the unrolling system in different cultural directions. Yet electrification in some form was a necessary, unavoidable phase for the technium. The internet that followed it, too, was inevitable, but the character of its incarnation is contingent on the tenor of the technologies that preceded it. Telephones were inevitable, but the iPhone wasn't. We accept the biological analog: Human adolescence is inevitable, but delinquency is not. The exact pattern that the inevitable teenagehood manifests in any individual will depend in part on his or her biology, which depends in part on his or her past health and environment but also hinges on his or her free-will choices.

Like personality, technology is shaped by a triad of forces. The primary driver is preordained developmentâwhat technology wants. The second driver is the influence of technological history, the gravity of the past, as in the way the size of a horse's yoke determines the size of a space rocket. The third force is society's collective free will in shaping the technium, or our choices. Under the first force of inevitability, the path of technological evolution is steered both by the laws of physics and by self-organizing tendencies within its large, complex, adaptive system. The technium will tend toward certain macroforms, even if you rerun the tape of time. What happens next is contingent on the second force, or what has already happened, and so the momentum of history constrains our choices forward. These two forces channel the technium along a limited path and severely restrict our choices. We like to think that “anything is possible next,” but in fact anything is not possible in technology.

In contrast to these two, the third force is our free will to make individual choices of use and collective policy decisions. Compared to all possibilities that we can imagine, we have a very narrow range of choices. But compared to 10,000 years ago, or even 1,000 years ago, or even last year, our possibilities are expanding. Although restricted in the cosmic sense, we have more choice than we know what to do with. And via the engine of the technium, these real choices will keep expanding (even though the larger path is preordained).

This paradox is recognized not just by historians of technology but by ordinary historians as well. In the view of cultural historian David Apter, “Human freedom actually exists within the limits set by the historical process. While not everything is possible, there is much that can still be chosen.” Historian of technology Langdon Winner sums up this convergence of free will and the ordained in these terms: “Technology moves steadily onward as if by cause and effect. This does not deny human creativity, intelligence, idiosyncrasy, chance, or the willful desire to head in one direction rather than another. All of these are absorbed into the process and become moments in the progressions.”

The Triad of Biological Evolution.

The three evolutionary vectors in life.

The three evolutionary vectors in life.

It is no coincidence that the triadic nature of the technium is the same as the triadic nature of biological evolution. If the technium is indeed the extended acceleration of the evolution of life, it should be governed by the same three forces.

One vector is the inevitable. The basic laws of physics and emergent self-organization drive evolution toward certain forms. Specific species (either biological or technological) are unpredictable in their microdetails, but the macropatterns (electrical motors, binary computing) are ordained by the physics of matter and self-organization. This inescapable force can be thought of as the structural inevitability of biological and technological evolution (shown as the lower left corner in the diagram above).

The second corner of the triad is the historical/contingent aspect of evolutionary change (lower right). Accidents and circumstantial opportunities bend the course of evolution this way and that, and those contingencies add up over time to create ecosystems with their own internal momentum. The past matters.

The third force working within evolution is the adaptive functionâthe relentless engine of optimization and creative innovation that con-tinually solves the problems of survival. In biology this is the incredible force of unconscious, blind natural selection (shown as the top corner).

The Triad of Technological Evolution.

In the technium, the functional vector is occupied by an equivalent force: the intentional.

In the technium, the functional vector is occupied by an equivalent force: the intentional.

But in the technium the adaptive function is not unconscious, as it is in natural selection. Instead it is open to human free will and choice. This intentional domain consists of the many decisions we make in the political expressions of inevitable inventions and of the billions of personal decisions individuals make about whether (and how) they use or avoid certain inventions. In biological evolution there is no designer, but in the technium there is an intelligent designerâSapiens. And of course, this conscious open design (shown as the top corner) is why the technium has become the most powerful force in the world.

The other two legs of technological evolution are identical to the other two legs of biological evolution. The basic laws of physics and emergent self-organization drive technological evolution through an inevitable series of structural formsâfour-wheeled vehicles, hemispherical boats, books of pages, etc. At the same time, the historical contingency of past inventions forms an inertia that bends evolution this way or thatâwithin the bounds of the inevitable developments. It is the third leg, the collective choice of free-willed individuals, that provides the character of the technium. And just as our free-will choices in our individual lives create the kind of person we are (our ineffable “person”), our choices, too, shape the technium.

We may not be able to choose the macroscale outlines of an industrial automation systemâassembly-line factories, fossil-fuel power, mass education, allegiance to the clockâbut we can choose the character of those parts. We have latitude in selecting the defaults of our mass education, so that we can nudge the system to maximize equality or to favor excellence or to foster innovation. We can bias the invention of the industrial assembly line either toward optimization of output or toward optimization of worker skills; those two paths yield different cultures. Every technological system can be set with alternative defaults that will change the character and personality of that technology.

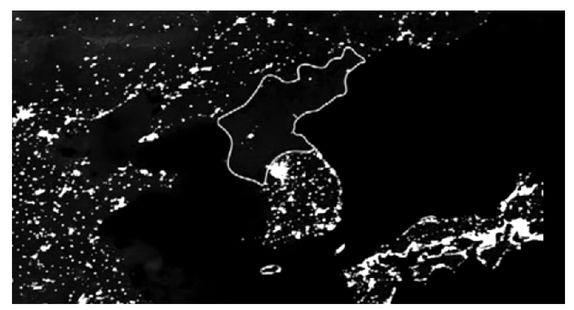

The consequences of choice can easily be seen from space. Satellites sweeping over the skies record city lights at night. From orbit each lighted town on the Earth below acts like a pixel in a night portrait of the technium. An evenly distributed coat of light indicates technological development. In Asia the steady scatter of light is interrupted by a large, dark, unlit blob. The dark outline follows the exact contour of the renegade country North Korea.

North Korea at Night.

The absence of modern technological abundance displayed by night satellite photography over east Asia. The outline of North Korea is drawn in white.

The absence of modern technological abundance displayed by night satellite photography over east Asia. The outline of North Korea is drawn in white.

Paul Romer, an economist at Stanford, points out that this remarkable negative space is the result of political policy. All the technological ingredients for nighttime light exist for North Korea, as evidenced by the brightly lit areas surrounding it, but as a country North Korea has adopted an expression of an electrical system that is sparse and minimal. The result is a stunning map of technological choice.

In

Nonzero,

author Robert Wright offers a wonderful analogy for understanding the role of the inevitable as applied to technology, which I paraphrase here. It's appropriate, Wright says, to claim that the destiny of a tiny seed, say, a poppy seed, is to grow into a plant. Flower yields seed, seed sprouts plant, according to an eternal fixed routine burned in by a billion years of flowers. Sprouting is what seeds do. In that fundamental sense, it is inevitable that a poppy seed becomes a plant, even though a fair number of poppy seeds wind up on bagels. We don't require that 100 percent of seeds arrive at their next stage to acknowledge the inexorable direction of the poppy's growth because we know that inside the poppy seed is a DNA program. The seed “wants” to be a plant. More precisely, the poppy seed is designed to grow stems, leaves, and flowers of a precise type. We regard the destiny of the seed less as the statistical probability of how many complete the journey, and more as a matter of what it is designed for.

Nonzero,

author Robert Wright offers a wonderful analogy for understanding the role of the inevitable as applied to technology, which I paraphrase here. It's appropriate, Wright says, to claim that the destiny of a tiny seed, say, a poppy seed, is to grow into a plant. Flower yields seed, seed sprouts plant, according to an eternal fixed routine burned in by a billion years of flowers. Sprouting is what seeds do. In that fundamental sense, it is inevitable that a poppy seed becomes a plant, even though a fair number of poppy seeds wind up on bagels. We don't require that 100 percent of seeds arrive at their next stage to acknowledge the inexorable direction of the poppy's growth because we know that inside the poppy seed is a DNA program. The seed “wants” to be a plant. More precisely, the poppy seed is designed to grow stems, leaves, and flowers of a precise type. We regard the destiny of the seed less as the statistical probability of how many complete the journey, and more as a matter of what it is designed for.

To claim that the technium pushes itself through certain inevitable technological forms is not to say that every technology was a mathematical certainty. Rather, it indicates a direction more than a destiny. More precisely, the technium's long-term trends reveal the design of the technium; this design indicates what the technium is built to do.

Inevitability is not a flaw. Inevitability makes prediction easier. The better we can forecast, the better we can be prepared for what comes. If we can discern the large outlines of persistent forces, we can better educate our children in the appropriate skills and literacies need for thriving in that world. We can shift the defaults in our laws and public institutions to reflect that coming reality. If, for instance, we realize that everyone's full DNA will be sequenced from birth or before (that is inevitable), then instructing everyone in genetic literacy becomes essential. Each must know the limits to what can and cannot be gleaned from this code, how it varies or does not among related individuals, what might impact its integrity, what information about it can be shared, what concepts such as “race” and “ethnicity” mean in this context, and how to use this knowledge to get therapeutics tailored to it. There's a whole world to open up, and it will take time, but we can begin to sort these choices out now because its arrival, in alignment with the exotropic principles, is pretty inevitable.

As the technium progresses, better tools for forecasting and prediction help us spot the inevitable. To return to the adolescence analogy, because we can anticipate the inevitable onset of human adolescence, we are better able to thrive in it. Teenagers are biologically compelled to take risks as a means of establishing their independence. Evolution “wants” risky teenagers. Knowing that risky behavior is expected in adolescence is both reassuring to teenagers (you are normal, not a freak) and to society (they will grow out of it) and an invitation to harness that normal riskiness for improvement and gain. If we ascertain that a global web of continuous connection is an inevitable phase in a growing civilization, then we can both be reassured by this inevitability and take it as an invitation to make the best global web we can.

Other books

Canada Under Attack by Jennifer Crump

Happy Medium: (Intermix) by Meg Benjamin

If Tomorrow Never Comes (Harper Falls Book 2) by Williams, Mary J.

White Lies by Jeremy Bates

Vanished by Mackel, Kathryn

If Death Ever Slept by Stout, Rex

His Dark Lady by Victoria Lamb

Seduced by Mistake - A Sensual Billionaire and Interracial BWWM Erotic Romance from Steam Books by Sinclair, Sandra, Books, Steam

The Snake River by Win Blevins