What Technology Wants (22 page)

Read What Technology Wants Online

Authors: Kevin Kelly

Just as in technology, the abstract core of an art form will crystallize into culture when the solvent is ready. It may appear more than once. But any particular species of creation will be flooded with irreplaceable texture and personality. If Rowling had not written Harry Potter, someone else would have written a similar story in broad outlines, because so many have already produced parallel parts. But the Harry Potter books, the ones that exist in their exquisite peculiar details, could not have been written by anyone other than Rowling. It is not the particular genius of human individuals like Rowling that is inevitable but the unfolding genius of the technium as a whole.

As in biological evolution, any claim of inevitability is difficult to prove. Convincing proof requires rerunning a progression more than once and showing that the outcome is the same each time. You must show a skeptic that no matter what perturbations are thrown at the system, it yields an identical result. To claim that the large-scale trajectory of the technium is inevitable would mean demonstrating that if we reran history, the same abstracted inventions would arise again and in roughly the same relative order. Without a reliable time machine, there'll be no indisputable proof, but we do have three types of evidence strongly suggesting that the paths of technologies are inevitable:

1. In all times we find that most inventions and discoveries have been made independently by more than one person.

2. In ancient times we find independent timelines of technology on different continents converging upon a set order.

3. In modern times we find sequences of improvement that are difficult to stop, derail, or alter.

In regard to the first point, we have a very clear modern record that simultaneous discovery is the norm in science and technology and not unknown in the arts. The second thread of evidence about ancient times is more difficult to produce because it entails tracking ideas during a period without writing. We must rely on the hints of buried artifacts in the archaeological record. Some of these suggest that independent discoveries converge in parallel to a uniform sequence of invention.

Until rapid communication networks wrapped the globe in stunning instantaneity, progress in civilization unrolled chiefly as independent strands on different continents. Earth's slippery landmasses, floating on tectonic plates, are giant islands. This geography produces a laboratory for testing parallelism. From 50,000 years ago, at the birth of Sapiens, until the year 1000 C.E. when sea travel and land communication ramped up, the sequence of inventions and discoveries on the four major continental landmassesâEurope, Africa, Asia, and the Americasâmarched on as independent progressions.

In prehistory the diffusion of innovations might advance a few miles a year, consuming generations to traverse a mountain range and centuries to cross a country. An invention born in China might take a millennium to reach Europe, and it would never reach America. For thousands of years, discoveries in Africa trickled out very slowly to Asia and Europe. The American continents and Australia were cut off from the other continents by impassable oceans until the age of sailing ships. Any technology imported to America came over via a land bridge in a relatively short window between 20,000 and 10,000 B.C.E. and almost none thereafter. Any migration to Australia was also via a geologically temporary land bridge that closed 30,000 years ago, with only marginal flow afterward. Ideas primarily circulated within one landmass. The great cradle of societal discovery two millennia agoâEgypt, Greece, and the Levantâsat right between continents, making the common boundaries for that crossover spot meaningless. Yet despite ever-speedy conduits between adjacent areas, inventions still circulated slowly within one continental mass and rarely crossed oceans.

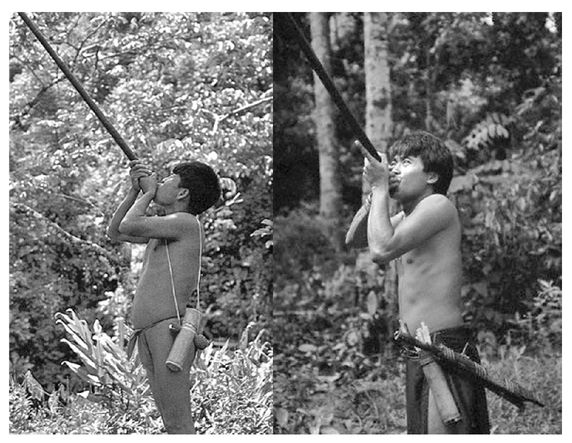

The enforced isolation back then gives us a way to rewind the tape of technology. According to archaeological evidence the blowgun was invented twice, once in the Americas and once in the islands of Southeast Asia. It was unknown anywhere else outside these two distant regions. This drastic separation makes the birth of the blowgun a prime example of convergent invention with two independent origins. The gun as devised by these two separate cultures is expectedly similarâa hollow tube, often carved in two halves bound together. In essence it is a bamboo or cane pipe, so it couldn't be much simpler. What's remarkable is the nearly identical set of inventions supporting the air pipe. Tribes in both the Americas and Asia use a similar kind of dart padded by a fibrous piston, both coat the ends with a poison that is deadly to animals but does not taint the meat, both carry the darts in a quill to prevent the poisoned tip from accidentally pricking the skin, and both employ a similarly peculiar stance when shooting. The longer the pipe, the more accurate the trajectory, but the longer the pipe the more it wavers during aiming. So in both America and Asia the hunters hold the pipe in a nonintuitive stance, with both hands near the mouth, elbows out, and gyrate the shooting end of the pipe in small circles. On each small revolution the tip will briefly cover the target. Accuracy, then, is a matter of the exquisite timing of when to blow. All this invention arose twice, like the same crystals found on two worlds.

Parallels in Blow Gun Culture.

Shooting position for a blowgun in the Amazon (left) compared to the position in Borneo (right).

Shooting position for a blowgun in the Amazon (left) compared to the position in Borneo (right).

In prehistory, parallel paths were played out again and again. From the archaeological record we know technicians in West Africa developed steel centuries before the Chinese did. In fact, bronze and steel were discovered independently on four continents. Native Americans and Asians independently domesticated ruminants such as llamas and cattle. Archaeologist John Rowe compiled a list of 60 cultural innovations common to two civilizations separated by 12,000 kilometers: the ancient Mediterranean and the high Andean cultures. Included on his list of parallel inventions are slingshots, boats made of bundled reeds, circular bronze mirrors with handles, pointed plumb bobs, and pebble-counting boards, or what we call abacus. Between societies, recurring inventions are the norm. Anthropologists Laurie Godfrey and John Cole conclude that “cultural evolution followed similar trajectories in various parts of the world.”

But perhaps there was far more communication between civilizations in the ancient world than we sophisticated moderns think. Trade in prehistoric times was very robust, but trade between continents was still rare. Nonetheless, with little evidence, a few minority theories (called the Shang-Olmec hypothesis) claim Mesoamerican civilizations maintained substantial transoceanic trade with China. Other speculations suggest extended cultural exchange between the Maya and west Africa, or between the Aztecs and Egypt (those pyramids in the jungle!), or even between the Maya and the Vikings. Most historians discount these possibilities and similar theories about deep, ongoing relations between Australia and South America or Africa and China before 1400. Beyond some superficial similarities in a few art forms, there is no empirical archaeological or recorded evidence of sustained transoceanic contact in the ancient world. Even if a few isolated ships from China or Africa might have reached, say, the shores of the pre-Columbian new world, these occasional landings would not have been sufficient to kindle the many parallels we find. It is highly improbable that the sewed-and-pitched bark canoe of the northern Australian aborigines came from the same source as the sewed-and-pitched bark canoe of the American Algonquin. It is much more likely that they are examples of convergent invention and arose independently on parallel tracks.

When viewed along continental tracks, a familiar sequence of inventions plays out. Each technological progression around the world follows a remarkably similar approximate order. Stone flakes yield to control of fire, then to cleavers and ball weapons. Next come ocher pigments, human burials, fishing gear, light projectiles, holes in stones, sewing, and figurine sculptures. The sequence is fairly uniform. Knifepoints always follow fire, human burials always follow knifepoints, and the arch precedes welding. A lot of the ordering is “natural” mechanics. You obviously need to be able to master blades before you make an ax. And textiles always follow sewing, since threads are needed for any kind of fabric. But many other sequences don't have a simple causal logic. There is no obvious reason that we are currently aware of why the first rock art always precedes the first sewing technology, yet it does each time. Metalwork does not have to follow claywork (pottery), but it always does.

Geographer Neil Roberts examined the parallel paths of domestication of crops and animals on four continents. Because the potential biological raw material on each continent varies so greatly (a theme explored in full by Jared Diamond in

Guns, Germs, and Steel

), only a few native species of crops or animals are first tamed on more than one landmass. Contrary to earlier assumptions, agriculture and animal husbandry were not invented once and then diffused around the world. Rather, as Roberts states, “Bio-archeological evidence taken overall indicates that global diffusion of domesticates was rare prior to the last 500 years. Farming systems based on the three great grain cropsâwheat, rice, and mazeâhave independent centers of origin.” The current consensus is that agriculture was (re)invented six times. And this “invention” is a series of inventions, a string of domestications and tools. The order of these inventions and tamings is similar across regions. For instance, on more than one continent humans domesticated dogs before camels and grains before root crops.

Guns, Germs, and Steel

), only a few native species of crops or animals are first tamed on more than one landmass. Contrary to earlier assumptions, agriculture and animal husbandry were not invented once and then diffused around the world. Rather, as Roberts states, “Bio-archeological evidence taken overall indicates that global diffusion of domesticates was rare prior to the last 500 years. Farming systems based on the three great grain cropsâwheat, rice, and mazeâhave independent centers of origin.” The current consensus is that agriculture was (re)invented six times. And this “invention” is a series of inventions, a string of domestications and tools. The order of these inventions and tamings is similar across regions. For instance, on more than one continent humans domesticated dogs before camels and grains before root crops.

Archaeologist John Troeng cataloged 53 prehistoric innovations beyond agriculture that independently originated not just twice but three times in three distinct separate regions of the globe: Africa, western Eurasia, and east Asia/Australia. Twenty-two of the inventions were also discovered by inhabitants of the Americas, meaning these innovations spontaneously erupted on four continents. The four regions are sufficiently separated that Troeng reasonably accepts that any invention in them is an independent parallel discovery. As technology invariably does, one invention prepares the ground for the next, and every corner of the technium evolves in a seemingly predetermined sequence.

With the help of a statistician, I analyzed the degree to which the four sequences of these 53 inventions paralleled one another. I found they correlated to an identical sequence by a coefficiency of 0.93 for the three regions and 0.85 for all four regions. In layman's terms, a coefficiency above 0.50 is better than random, while a coefficiency of 1.00 is a perfect match; a coefficiency of 0.93 indicates that the sequences of discoveries were nearly the same, and 0.85 slightly less so. That degree of overlap in the sequence is significant given the incomplete records and the loose dating inherent in prehistory. In essence, the direction of technological development is the same anytime it happens.

To confirm this direction, research librarian Michele McGinnis and I also compiled a list of the dates when preindustrial inventions, such as the loom, sundial, vault, and magnet, first appeared on each of the five major continents: Africa, the Americas, Europe, Asia, and Australia. Some of these discoveries occurred during eras when communication and travel were more frequent than in prehistoric times, so the independence of each invention is less certain. We found historical evidence for 83 innovations that were invented on more than one continent. And again, when matched up, the sequence of technology's unfolding in Asia is similar to that in the Americas and Europe to a significant degree.

We can conclude that in historic times as well as in prehistory, technologies with globally distinct origins converge along the same developmental path. Independent of the different cultures that host it, or the diverse political systems that rule it, or the different reserves of natural resources that feed it, the technium develops along a universal path. The large-scale outlines of technology's course are predetermined.

Anthropologist Kroeber warns, “Inventions are culturally determined. Such a statement must not be given a mystical connotation. It does not mean, for instance, that it was predetermined from the beginning of time that type printing would be discovered in Germany about 1450, or the telephone in the United States in 1876.” It means only that when all the required conditions generated by previous technologies are in place, the next technology can arise. “Discoveries become virtually inevitable when prerequisite kinds of knowledge and tools accumulate,” says sociologist Robert Merton, who studied simultaneous inventions in history. The ever-thickening mix of existing technologies in a society creates a supersaturated matrix charged with restless potential. When the right idea is seeded within, the inevitable invention practically explodes into existence, like an ice crystal freezing out of water. Yet as science has shown, even though water is destined to become ice crystals when it is cold enough, no two snowflakes are the same. The path of freezing water is predetermined, but there is great leeway, freedom, and beauty in the individual expression of its predestined state. The actual pattern of each snowflake is unpredictable, although its archetypal six-sided form is determined. For such a simple molecule, its variations upon an expected theme are endless. That's even truer for extremely complex inventions today. The crystalline form of the incandescent lightbulb or the telephone or the steam engine is ordained, while its unpredictable expression will vary in a million possible formations, depending on the conditions in which it evolved.

Other books

Torn - Part Three (The Torn Series) by Callahan, Ellen

The Romanov Bride by Robert Alexander

Esta es nuestra fe. Teología para universitarios by Luis González-Carvajal Santabárbara

Doomed Queens by Kris Waldherr

The Dragon Lord by Morwood, Peter

The Story Begins by Modou Fye

Relentless (Relentless #1) by Alyson Reynolds

Acceptable Behavior by Jenna Byrnes

The Secret Heiress by Susie Warren

Tristan on a Harley (Louisiana Knights Book 3) by Jennifer Blake