What Technology Wants (21 page)

Read What Technology Wants Online

Authors: Kevin Kelly

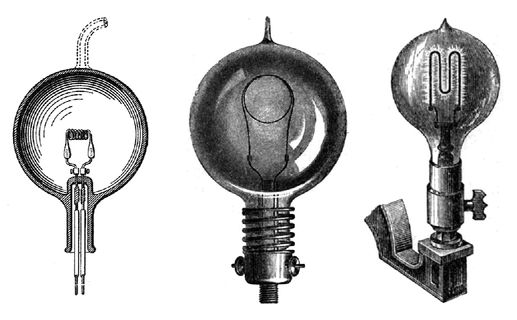

Varieties of the Lightbulb.

Three independently invented electric lightbulbs: Edison's, Swan's, and Maxim's.

Three independently invented electric lightbulbs: Edison's, Swan's, and Maxim's.

On the other hand, if technologies really are inevitable, then we have only the illusion of choice, and we should smash all technologies to be free of this spell. I'll address these central concerns later, but I want to note one curious fact about this last belief. While many people claim to believe the notion of technological determinism is wrong (in either sense of that word), they don't act that way. No matter what they rationally think about inevitability, in my experience

all

inventors and creators act as if their own invention and discovery is imminently simultaneous. Every creator, inventor, and discoverer that I have known is rushing their ideas into distribution before someone else does, or they are in a mad hurry to patent before their competition does, or they are dashing to finish their masterpiece before something similar shows up. Has there ever been an inventor in the last two hundred years who felt that no one else would ever come up with his idea (and who was right)?

all

inventors and creators act as if their own invention and discovery is imminently simultaneous. Every creator, inventor, and discoverer that I have known is rushing their ideas into distribution before someone else does, or they are in a mad hurry to patent before their competition does, or they are dashing to finish their masterpiece before something similar shows up. Has there ever been an inventor in the last two hundred years who felt that no one else would ever come up with his idea (and who was right)?

Nathan Myhrvold is a polymath and serial inventor who used to direct fast-paced research at Microsoft but wanted to accelerate the pace of innovation in other areas outside the digital realmâsuch as surgery, metallurgy, or archaeologyâwhere innovation was often a second thought. Myhrvold came up with an idea factory called Intellectual Ventures. Myhrvold employs an interdisciplinary team of very bright innovators to sit around and dream up patentable ideas. These eclectic one- or two-day gatherings will generate 1,000 patents per year. In April 2009, author Malcolm Gladwell profiled Myhrvold's company in the

New Yorker

to make the point that it does not take a bunch of geniuses to invent the next great thing. Once an idea is “in the air” its many manifestations are inevitable. You just need a sufficient number of smart, prolific people to start catching them. And of course a lot of patent lawyers to patent what you generate in bulk. Gladwell observes, “The genius is not a unique source of insight; he is merely an efficient source of insight.”

New Yorker

to make the point that it does not take a bunch of geniuses to invent the next great thing. Once an idea is “in the air” its many manifestations are inevitable. You just need a sufficient number of smart, prolific people to start catching them. And of course a lot of patent lawyers to patent what you generate in bulk. Gladwell observes, “The genius is not a unique source of insight; he is merely an efficient source of insight.”

Gladwell never got around to asking Myhrvold how many of his own lab's inventions turn out to be ideas that others come up with, so I asked Myhrvold, and he replied: “Oh, about 20 percentâthat we know about. We only file to patent one third of our ideas.”

If parallel invention is the norm, then even Myhrvold's brilliant idea of creating a patent factory should have occurred to others at the same time. And of course it has. Years before the birth of Intellectual Ventures, internet entrepreneur Jay Walker launched Walker Digital Labs. Walker is famous for inventing Priceline, a name-your-own-price reservation system for hotels and airline flights. In his invention laboratory Walker set up an institutional process whereby interdisciplinary teams of brainy experts sit around thinking up ideas that would be useful in the next 20 years or soâthe time horizon of patents. They winnow the thousands of ideas they come up with and refine a selection for eventual patenting. How many ideas do they abandon because they, or the patent office, find that the idea has been “anticipated” (the legal term meaning “scooped”) by someone else? “It depends on the area,” Walker says. “If it is a very crowded space where lots of innovation is happening, like e-commerce, and it is a âtool,' probably 100 percent have been thought of before. We find the patent office rejects about two-thirds of challenged patents as âanticipated.' Another space, say gaming inventions, about a third are either blocked by prior art or other inventors. But if the invention is a complex system, in an unusual space, there won't be many others. Look, most invention is a matter of time . . . of when, not if.”

Danny Hillis, another polymath and serial inventor, is cofounder of an innovative prototype shop called Applied Minds, which is another idea factory. As you might guess from the name, they use smart people to invent stuff. Their corporate tagline is “the little Big Idea company.” Like Myhrvold's Intellectual Ventures, they generate tons of ideas in interdisciplinary areas: bioengineering, toys, computer vision, amusement rides, military control rooms, cancer diagnostics, and mapping tools. Some ideas they sell as unadorned patents; others they complete as physical machines or operational software. I asked Hillis, “What percentage of your ideas do you find out later someone else had before you, or at the same time as you, or maybe even after you?” As a way of answering, Hillis offered a metaphor. He views the bias toward simultaneity as a funnel. He says, “There might be tens of thousands of people who conceive the possibility of the same invention at the same time. But less than one in ten of them imagines

how

it might be done. Of these who see how to do it, only one in ten will actually think through the practical details and specific solutions. Of these only one in ten will actually get the design to work for very long. And finally, usually only one of all those many thousands with the idea will get the invention to stick in the culture. At our lab we engage in all these levels of discovery, in the expected proportions.” In other words, in the conceptual stage, simultaneity is ubiquitous and inevitable; your brilliant ideas will have lots of coparents. But there's less coparentage at each reducing stage. When you are trying to bring an idea to market, you may be alone, but by then you are a mere pinnacle of a large pyramid of others who all had the same idea.

how

it might be done. Of these who see how to do it, only one in ten will actually think through the practical details and specific solutions. Of these only one in ten will actually get the design to work for very long. And finally, usually only one of all those many thousands with the idea will get the invention to stick in the culture. At our lab we engage in all these levels of discovery, in the expected proportions.” In other words, in the conceptual stage, simultaneity is ubiquitous and inevitable; your brilliant ideas will have lots of coparents. But there's less coparentage at each reducing stage. When you are trying to bring an idea to market, you may be alone, but by then you are a mere pinnacle of a large pyramid of others who all had the same idea.

The Inverted Pyramid of Invention.

Time proceeds down, as the numbers involved at each level decrease.

Time proceeds down, as the numbers involved at each level decrease.

Any reasonable person would look at that pyramid and say the likelihood of someone getting a lightbulb to stick is 100 percent, although the likelihood of Edison's being the inventor is, well, one in 10,000. Hillis also points out another consequence. Each stage of the incarnation can recruit new people. Those toiling in the later stages may not have been among the earliest pioneers of the idea. Given the magnitude of reduction, the numbers suggest that it is improbable that the first person to make an invention stick was also the first to think of the idea.

Another way to read this chart is to recognize that ideas start out abstract and become more specific over time. As universal ideas become more specific they become less inevitable, more conditional, and more responsive to human volition. Only the conceptual essence of an invention or discovery is inevitable. The specifics of how this essential core (the “chairness” of a chair) is manifested in practice (in plywood, or with a rounded back) are likely to vary widely depending on the resources available to the inventors at hand. The more abstract the new idea remains, the more universal and simultaneous it will be (shared by tens of thousands). As it steadily becomes embodied stage by stage into the constraints of a very particular material form, it is shared by fewer people and becomes less and less predictable. The final design of the first marketable lightbulb or transistor chip could not have been anticipated by anyone, even though the concept was inevitable.

What about great geniuses like Einstein? Doesn't he disprove the notion of inevitability? The conventional wisdom is that Einstein's wildly creative ideas about the nature of the universe, first announced to the world in 1905, were so out of the ordinary, so far ahead of his time, and so unique that if he had not been born we might not have his theories of relativity even today, a century later. Einstein was a unique genius, no doubt. But as always, others were working on the same problems. Hendrik Lorentz, a theoretical physicist who studied light waves, introduced a mathematical structure of space-time in July 1905, the same year as Einstein. In 1904 the French mathematician Henri Poincare pointed out that observers in different frames will have clocks that will “mark what one may call the local time” and that “as demanded by the relativity principle the observer cannot know whether he is at rest or in absolute motion.” And the 1911 winner of the Nobel Prize in physics, Wilhelm Wien, proposed to the Swedish committee that Lorentz and Einstein be jointly awarded a Nobel Prize in 1912 for their work on special relativity. He told the committee, “While Lorentz must be considered as the first to have found the mathematical content of the relativity principle, Einstein succeeded in reducing it to a simple principle. One should therefore assess the merits of both investigators as being comparable.” (Neither won that year.) However, according to Walter Isaacson, who wrote a brilliant biography of Einstein's ideas,

Einstein: His Life and Universe,

“Lorentz and Poincare never were able to make Einstein's leap even

after

they read his paper.” But Isaacson, a celebrator of Einstein's special genius for the improbable insights of relativity, admits that “someone else would have come up with it, but not for at least ten years or more.” So the greatest iconic genius of the human race is able to leap ahead of the inevitable by maybe 10 years. For the rest of humanity, the inevitable happens on schedule.

Einstein: His Life and Universe,

“Lorentz and Poincare never were able to make Einstein's leap even

after

they read his paper.” But Isaacson, a celebrator of Einstein's special genius for the improbable insights of relativity, admits that “someone else would have come up with it, but not for at least ten years or more.” So the greatest iconic genius of the human race is able to leap ahead of the inevitable by maybe 10 years. For the rest of humanity, the inevitable happens on schedule.

The technium's trajectory is more fixed in certain realms than in others. Based on the data, “mathematics has more apparent inevitability than the physical sciences,” wrote Simonton, “and technological endeavors appear the most determined of all.” The realm of artistic inventionsâthose engendered by the technologies of song, writing, media, and so onâis the home of idiosyncratic creativity, seemingly the very antithesis of the inevitable, but it also can't fully escape the currents of destiny.

Hollywood movies have an unnerving habit of arriving in pairs: two movies that arrive in theaters simultaneously featuring an apocalyptic hit by asteroids (

Deep Impact

and

Armageddon

), or an ant hero (

A Bug's Life

and

Antz

), or a hardened cop and his reluctant dog counterpart (

K-9

and

Turner & Hooch

). Is this similarity due to simultaneous genius or to greedy theft? One of the few reliable laws in the studio and publishing businesses is that the creator of a successful movie or novel will be immediately sued by someone who claims the winner stole their idea. Sometimes it

was

stolen, but just as often two authors, two singers, or two directors came up with similar works at the same time. Mark Dunn, a library clerk, wrote a play,

Frank's Life,

that was performed in 1992 in a small theater in New York City.

Frank's Life

is about a guy who is unaware that his life is a reality TV program. In his suit against the producers of the 1998 movie

The Truman Show,

Dunn lists 149 similarities between his story and theirsâwhich is a movie about a guy who is unaware that his life is a reality TV program. However,

The Truman Show

's producers claim they have a copyrighted, dated script of the movie from 1991, a year before

Frank's Life

was staged. It is not too hard to believe that the idea of a movie about an unwitting reality TV hero was inevitable.

Deep Impact

and

Armageddon

), or an ant hero (

A Bug's Life

and

Antz

), or a hardened cop and his reluctant dog counterpart (

K-9

and

Turner & Hooch

). Is this similarity due to simultaneous genius or to greedy theft? One of the few reliable laws in the studio and publishing businesses is that the creator of a successful movie or novel will be immediately sued by someone who claims the winner stole their idea. Sometimes it

was

stolen, but just as often two authors, two singers, or two directors came up with similar works at the same time. Mark Dunn, a library clerk, wrote a play,

Frank's Life,

that was performed in 1992 in a small theater in New York City.

Frank's Life

is about a guy who is unaware that his life is a reality TV program. In his suit against the producers of the 1998 movie

The Truman Show,

Dunn lists 149 similarities between his story and theirsâwhich is a movie about a guy who is unaware that his life is a reality TV program. However,

The Truman Show

's producers claim they have a copyrighted, dated script of the movie from 1991, a year before

Frank's Life

was staged. It is not too hard to believe that the idea of a movie about an unwitting reality TV hero was inevitable.

Writing in the

New Yorker,

Tad Friend tackled the issue of synchronistic cinematic expression by suggesting that “the giddiest aspect of copyright suits is how often the studios try to prove that their story was so derivative that they couldn't have stolen it from only one source.” The studios essentially say: Every part of this movie is a cliche stolen from plots/stories/themes/jokes that are in the air. Friend continues,

New Yorker,

Tad Friend tackled the issue of synchronistic cinematic expression by suggesting that “the giddiest aspect of copyright suits is how often the studios try to prove that their story was so derivative that they couldn't have stolen it from only one source.” The studios essentially say: Every part of this movie is a cliche stolen from plots/stories/themes/jokes that are in the air. Friend continues,

You might think that mankind's collective imagination could churn up dozens of fictional ways to track a tornado, but there seems to be only one. When Stephen Kessler sued Michael Crichton for “Twister,” he was upset because his script about tornado chasers, “Catch the Wind,” had placed a data-collection device called Toto II in the whirlwind's path, just like “Twister”'s data-collecting Dorothy. Not such a coincidence, the defense pointed out: years earlier two other writers had written a script called “Twister” involving a device called Toto.

Plots, themes, and puns may be inevitable once they are in the cultural atmosphere, but we yearn to encounter completely unexpected creations. Every now and then we believe a work of art must be truly original, not ordained. Its pattern, premise, and message originate with a distinctive human mind and shine as unique as they are. Say an original mind with an original story like J. K. Rowling, author of the highly imaginative Harry Potter series. After Rowling launched Harry Potter in 1997 to great success, she successfully rebuffed a lawsuit by an American author who published a series of children's books 13 years earlier about Larry Potter, an orphaned boy wizard wearing glasses and surrounded by Muggles. In 1990 Neil Gaiman wrote a comic book about a dark-haired English boy who finds out on his 12th birthday that he is a wizard and is given an owl by a magical visitor. Or keep in mind a 1991 story by Jane Yolen about Henry, a boy who attends a magical school for young wizards and must overthrow an evil wizard. Then there's

The Secret of Platform 13,

published in 1994, which features a gateway on a railway platform to a magical underworld. There are many good reasons to believe J. K. Rowling when she claims she read none of these (for instance, very few of the Muggle books were printed and almost none were sold; and Gaiman's teenage-boy comics don't usually appeal to single moms) and many more reasons to accept the fact that these ideas arose in simultaneous spontaneous creation. Multiple invention happens all the time in the arts as well as technology, but no one bothers to catalog similarities until a lot of money or fame is involved. Because a lot of money swirls around Harry Potter we have discovered that, strange as it sounds, stories of boy wizards in magical schools with pet owls who enter their otherworlds through railway station platforms are inevitable at this point in Western culture.

The Secret of Platform 13,

published in 1994, which features a gateway on a railway platform to a magical underworld. There are many good reasons to believe J. K. Rowling when she claims she read none of these (for instance, very few of the Muggle books were printed and almost none were sold; and Gaiman's teenage-boy comics don't usually appeal to single moms) and many more reasons to accept the fact that these ideas arose in simultaneous spontaneous creation. Multiple invention happens all the time in the arts as well as technology, but no one bothers to catalog similarities until a lot of money or fame is involved. Because a lot of money swirls around Harry Potter we have discovered that, strange as it sounds, stories of boy wizards in magical schools with pet owls who enter their otherworlds through railway station platforms are inevitable at this point in Western culture.

Other books

Falling for the Pirate by Amber Lin

The Lessons by Elizabeth Brown

Sinfully Spellbound (Spells That Bind Book 1) by Lawson, Cassandra

The Tree In Changing Light by Roger McDonald

The Icing on the Corpse by Mary Jane Maffini

Lucky Bastard by S. G. Browne

Love and the Loathsome Leopard by Barbara Cartland

Trial & Error by Paul Levine

Honour Be Damned by Donachie, David