Where the Domino Fell - America And Vietnam 1945-1995 (13 page)

Read Where the Domino Fell - America And Vietnam 1945-1995 Online

Authors: James S. Olson,Randy W. Roberts

Tags: #History, #Americas, #United States, #Asia, #Southeast Asia, #Europe, #Military, #Vietnam War, #Modern (16th-21st Centuries), #20th Century, #World, #Humanities, #Social Sciences, #Political Science, #International Relations, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #International & World Politics, #Asian, #European, #eBook

Diem’s youngest brother, Ngo Dinh Nhu, was his closest associate as well as the political boss of South Vietnam from Phan Thiet Province to the Ca Mau Peninsula. Nicknamed “Smiley” by Americans because of a permanent smile fixed on his face, Nhu was privately contemptuous of the United States. Americans had too much power, too much money, and too little humility. Nhu was short on humility himself. A devout Roman Catholic educated at the École de Chartres in Paris, Nhu hated the Buddhists and wanted to “put the monks in their places.” He was commander of the Vietnamese Special Forces and transformed them into his own personal army of henchmen, hit men, and spies. Nhu, a heavy opium user and a chain smoker, admired Adolf Hitler. Next to Diem, Nhu was the most powerful man in South Vietnam.

Because of Diem’s vow of celibacy, it fell to Nhu’s wife, Tran Le Xuan, to serve as first lady or, in the words of her critics, the “Queen of Saigon.” She was completely Gallicized. Educated at private Catholic schools in France, she was more comfortable speaking French than using Vietnamese. Arrogant, intolerant, insensitive, and prudish, fancying herself a reincarnation of the ancient Trung sisters, she led public campaigns against card playing, adultery, blue movies, gambling, horse racing, fortune telling, boxing, divorce, prostitution, dancing, and beauty contests. She wanted to outlaw the use of “falsies” in women’s bras but gave up on the idea when she realized it would be impossible to enforce. Using her own private police force, Madame Nhu had people arrested for wearing loud clothing and boots or bizarre hairstyles. Her father, Tran Van Chuong, was a major landowner and during World War II had been foreign minister for the Japanese regime. He was minister of state for Diem and then ambassador to the United States.

Ensconced in power, the Ngo family then turned on its last real rival in South Vietnam—the Vietminh. Fewer than 10,000 Vietminh remained in South Vietnam after the Geneva Accords; the other 100,000 or so withdrew to North Vietnam to wait for the elections. Diem refused to call them Vietminh, preferring the derogatory term “Vietcong,” or “Vietnamese Communist.” Diem launched a violent campaign against the Vietcong late in 1955, using ARVN soldiers and village officials to expose them. His slogan: “Let us go mercilessly to wipe out the Vietcong, no longer considering them human beings.”

And that is just what Diem tried to do. Between late 1955 and early 1960, ARVN soldiers arrested more than 100,000 people accused of being Vietminh, even though at the most there were only 10,000 Vietminh in South Vietnam. Executions took place near the homes of the accused, so their bodies could be found and the village intimidated. Somewhere between 20,000 and 75,000 South Vietnamese were killed and another 100,000 sent to concentration camps for “reeducation.” Diem also desecrated Vietminh war memorials and cemeteries, an unforgivable insult in a culture practicing ancestor worship and family obedience. Though the terrorism successfully reduced the number of Vietminh in South Vietnam from 10,000 people in 1955 to only 3,000 in 1958, it inspired surviving Vietminh leaders to conduct a dedicated guerrilla war against the Diem government. Because most of Diem’s victims were simple peasants, the terrorism drove a greater wedge between the Vietnamese people and the government.

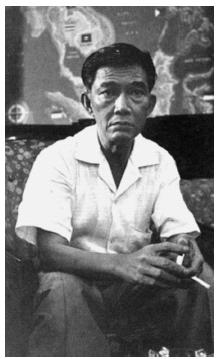

The Vietminh leader in South Vietnam was Le Duan, born in Quang Tri Province in 1908. As a student, Duan had become an anti-French nationalist. He spent most of the years between 1931 and 1945 in the French prison on Con Son Island. After World War II, he stayed in southern Vietnam. Convinced that the French were just trying to preserve their empire, Duan opposed the Geneva Accords of 1954—better to destroy French troops in the south just as the Vietminh had destroyed the French at Dienbienphu. The Flame of the South, so called for his commitment to reunification, Le Duan went along with Ho Chi Minh’s decision to sign the Geneva Accords, but when Ho called the Vietminh back to North Vietnam in 1954, Duan stayed behind. Between 1954 and 1956, the year reunification elections were supposed to take place, Vietcong activities had been primarily political: working with peasants, helping plant and harvest crops, delivering rice to markets, improving community buildings and peasant homes, and providing drugs and basic medical care. Diem’s decision to cancel the elections precipitated a bitter debate in North Vietnam. Most party members in North Vietnam were cautious about reigniting the armed struggle in the south. They were busy consolidating their power, and they wanted to avoid a confrontation with the United States. But most Vietminh who pulled out of South Vietnam after the Geneva Accords were native southerners who resented the division of Vietnam. The old ethnic rivalry between northern and southern Vietnamese was revived within the Vietcong. Southerners accused northerners of abandoning them, of enjoying the fruits of power in the north while southerners suffered under the oppression of Ngo Dinh Diem. While circumspect in his proposals, Le Duan represented that southern point of view. As early as 1956 Duan urged Ho Chi Minh to overthrow the Diem regime, but Ho was cautious, preferring political to military action. Duan was obedient and worked hard to keep southerners in line, but he knew their patience was running out. In December 1956 North Vietnamese leaders compromised, agreeing that firming up the revolution in North Vietnam was their priority while southerners should work to destabilize the Diem regime politically and defend themselves if necessary.

In mid-1957 the Vietcong launched their campaign against Diem. In 1958 they assassinated more than 1,100 village officials in South Vietnam, and they increased that number in 1959. Minh instructed the Vietcong not to engage in military operations; that would lead to defeat. Do not take land from a peasant. Emphasize nationalism rather than communism. Do not antagonize anyone if you can avoid it. Be selective in your violence. If an assassination is necessary, use a knife, not a rifle or grenade. It is too easy to kill innocent bystanders with guns and bombs, and accidental killings of the innocent will alienate peasants from the revolution. Once an assassination has taken place, make sure peasants know why the killing occurred. Vietcong assassins went after the most corrupt village officials first, those who stole from the peasants or raped women. Regardless of political affiliation, peasants were glad to see those officials dead. Where Diem had appointed Roman Catholics to preside over Buddhist villages, the Vietcong assassinated the Catholics, earning silent praise from local monks. And to strike terror into village leaders, to let everyone know that nobody was safe, the Vietcong sometimes targeted the best, most efficient officials for assassination. The Vietcong often decapitated their victims. Vietnamese spiritualism held that people who lost their heads were destined to an eternity of restless wandering in the world of spirits. Ho Chi Minh told the Vietcong that the quickest way to the heart of a peasant was land. The Vietcong seized the land from absentee landlords, gave it to poor farmers, and spread the word that the Vietcong robbed from the rich to give to the poor.

Diem responded to the deteriorating political situation in the only way he knew how—increasing the use of force, which played into the hands of the Vietcong. To keep peasants from being converted by Vietcong propaganda, Diem launched the Agroville Program, relocating peasants into hastily constructed villages placed along Vietcong infiltration routes. The villages were heavily defended and surrounded by barbed wire. It was difficult for the Vietcong to get in, but to the peasants the new villages looked like prisons. People were rounded up into forced labor gangs to build the camps and then were forcibly moved there, far from ancestral villages. Since Vietnamese peasants looked upon their family land with deep reverence, relocation was a spiritual and physical crisis. The resettlement enraged peasants. Diem had the National Assembly pass Law 10/59 in May 1959. Designed to wipe out the Vietcong, it created special military tribunals to arrest any individual “who commits or intends to commit crimes... against the State.” Equipped with portable guillotines, the tribunals rendered one of three verdicts: innocent, life in prison, and death. The ensuing trials were kangaroo courts. Nhu’s secret police took part in the trials, sometimes carrying out the guillotining of convicted “traitors.” For the moment, the campaign was effective. Diem’s terrorism was so widespread and capricious that innocent peasants were afraid even to be seen with suspected Vietcong. Large numbers of Vietcong either quit the party or were killed. Communist party membership in South Vietnam shrank to 3,000 in 1959. But the 10/59 campaign also terrorized thousands of innocent peasants who came to hate the Ngo family.

Finally, the regime corrupted the 1959 National Assembly elections. Although there were opposition candidates, the government prohibited newspapers from publishing their names or printing campaign literature. Opposition posters were not allowed to be displayed, nor could candidates opposed to Diem speak to gatherings of more than five people. In the southern part of the country, Nhu’s secret police worked as election officials, handing out ballots and watching how people voted. In the northern provinces, Can’s secret police performed the same functions. When it appeared that large numbers of people might not vote, the government passed an ordinance requiring them to carry a voter identification card that had been punched at the polls. When the election turned out to be a resounding victory for the Ngo family, Diem announced, “The people have spoken.”

In 1959 Diem’s increasing consolidation of power, along with the decline of the Vietcong, brought about a change in Communist party policy. Recognizing that it would probably take an armed struggle to overthrow South Vietnam, Ho Chi Minh gave in to Le Duan’s urgings and began infiltrating cadres into South Vietnam. At first they were southern-born Vietminh who had relocated to North Vietnam. After five years away from his family, one Vietminh remarked, “I was joyous to learn of my assignment to go south. I was eager to see my home village, to see my family, to get in contact with my wife.” Another decision was to prepare for a more protracted military struggle throughout Indochina. In May 1959 the North Vietnamese military established Group 559 to develop a means of moving people and supplies from North Vietnam to South Vietnam through Laos and Cambodia. Group 759, established in July, was to develop techniques for infiltrating South Vietnam by sea. Another project was to establish Indochina as a single strategic entity. In order to bring about the reunification of North and South Vietnam, the communists had to prevent the United States from securing control of Laos and Cambodia. In 1958 and 1959, with United States assistance, right-wing forces in Laos ousted the neutral government of Prince Souvanna Phouma and tightened their power. The Royal Army then attacked strongholds of the Pathet Lao, the Laotian communist guerrillas. The civil war in Laos worried North Vietnam. If the Royal Army succeeded in expelling the Pathet Lao from their mountain strongholds, Group 559 would be hard-pressed to get people and supplies into South Vietnam, since the Laotian mountains were the vital communication link. In September 1959 North Vietnam established Group 959 to provide supplies to Pathet Lao guerrillas and urged Vietnamese soldiers to join the fight. In 1960 North Vietnamese and Pathet Lao troops defeated the Royal Army along the border and secured the corridor Hanoi needed into South Vietnam. When the time was right, North Vietnam would begin moving large numbers of cadres, supplies, and eventually soldiers down that Laotian corridor into South Vietnam. It became known as the Ho Chi Minh Trail.