Where the Domino Fell - America And Vietnam 1945-1995 (26 page)

Read Where the Domino Fell - America And Vietnam 1945-1995 Online

Authors: James S. Olson,Randy W. Roberts

Tags: #History, #Americas, #United States, #Asia, #Southeast Asia, #Europe, #Military, #Vietnam War, #Modern (16th-21st Centuries), #20th Century, #World, #Humanities, #Social Sciences, #Political Science, #International Relations, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #International & World Politics, #Asian, #European, #eBook

For the permanent base camps Westmoreland made wooden barracks of high quality built on concrete slabs and equipped with hot showers. High-ranking officers enjoyed air-conditioned quarters in mobile trailers. Foremost Dairy and Meadowgold Dairies built fresh milk and ice cream plants at Qui Nhon and Cam Ranh Bay, and to supply troops in remote locations with fresh ice cream, Westmoreland built forty army ice cream plants. To make sure that the soldiers got three meals a day of fresh fruit, vegetables, meat, and dairy products, he built thousands of cold storage lockers throughout South Vietnam. To amuse the troops, he built the famous PXs—air-conditioned movie theaters, bowling alleys, and service clubs full of beer, Cokes, hot dogs, hamburgers, french fries, malts, sundaes, candy, and ice. No army in the history of the world had more of the amenities of home.

Of the women sent to South Vietnam as the war grew, about 11,000 were nurses. To deal with cases of sick and wounded soldiers, the Pentagon began to deploy army medical detachments in the spring of 1965. The 3rd Field Hospital went to Tan Son Nhut in April 1965, and the 58th Medical Battalion reached Long Binh in May. The 9th Field Hospital was stationed in Nha Trang in July, and it was followed by the 85th Evacuation Hospital in August, the 43rd Medical Group and the 523d Field Hospital in September, and the 1st Medical Battalion, 2nd Surgical Hospital, 51st Field Hospital, and 93rd Evacuation Hospital in November. Eventually, the army assigned forty-seven medical units to South Vietnam. Navy nurses worked on the USS

Repose

and the USS

Sanctuary,

hospital ships that sailed between the Demilitarized Zone and Danang off the coast of Vietnam in the South China Sea. Air force nurses worked on medevac aircraft evacuating the wounded to Japan, Okinawa, the Philippines, and the United States. There were no Marine Corps nurses.

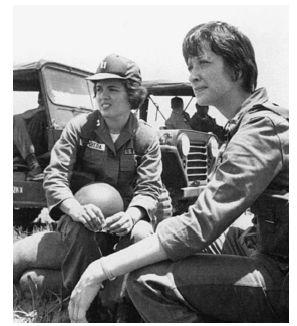

July 14, 1965—U.S. Army nurses Capt. Gladys E. Sepulveda, left, of Ponce, Puerto Rico, and 2nd Lt. Lois Ferrari, of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, rest on sandbags at Cam Ranh Bay in South Vietnam.

(Courtesy, Library of Congress.

)

Nursing may have been the most emotionally hazardous duty of the entire war. During the course of a tour of duty, day after day for an entire year, nurses were exposed constantly to sick and wounded young men. They frequently encountered men and boys younger than they who were suffering from massive wounds. The combination of helicopters and field hospitals allowed some soldiers to survive wounds that in any previous war would have been fatal. Sarah McGoran, an army nurse, saw wounds“so big you could put both your arms into them.” Napalm and white phosphorous bombs created a new definition of burns—“fourth degree.” In Kathryn Marshall's

In the Combat Zone,

published in 1987, a navy nurse speaks of burn victims who had been“essentially denuded. We used to talk about fourth-degree burns—you know, burns are labeled first, second, and third degree, but we had people who were burnt all the way through.” Some wounds were so horrific that medical terminology did not exist to describe them.“Horriblectomies were when they'd had so much taken out or removed. Horridzoma meant the initial grotesque injury but also the repercussions of the injury.” Rachel Smith had to numb herself“to the screams of teenaged boys whose bodies had been blown to bits, moaning for their mothers, begging for relief, praying for death. Pretty soon it just became another day's work for me. Otherwise, I would've gone nuts.” Later in the war, the nurses treated soldier-addicts, young men using opium, amphetamines, cocaine, and heroin to block out the war.“Nobody told me,” an army nurse recalled,“I was going to be taking care of so many strung-out motherfuckers. I mean, this was supposed to be a

war.”

Another 1,300 military women performed nonmedical jobs in Vietnam. Most were assigned to the Women's Army Corps, in which they worked as secretaries at MACV. Others were in the Army Signal Corps. Other military women were air traffic controllers, intelligence officers, decoders, or cartographers. For the most part, they were assigned to Saigon and the major bases in South Vietnam. Tens of thousands of civilian women had jobs in South Vietnam during the war. The American Red Cross sent women to Vietnam, as did such other service groups and relief organizations as the American Friends Service Committee, the Mennonite Central Committee, the Agency for International Development, Army Special Services, the USO, Supplemental Recreational Activities Overseas, Catholic Relief Services, and the Christian Missionary Alliance. Civilian women worked with the CIA's Air America and World Airways. Women came to South Vietnam with the international construction firms that had secured billions of dollars in government contracts. Among those construction firms were Brown and Root, Bechtel, and Martin Marietta.

In all, more than 50,000 American women served in Indochina in military and civilian capacities. Eight of them made the ultimate sacrifice. Seven military women died of accidents and disease; Lieutenant Sharon M. Lanz of the Army Nurse Corps died on June 8, 1969, when North Vietnamese rockets hit Chu Lai.

The widening of the ground war and bombing campaigns made infiltration of supplies from North Vietnam more difficult but did not stop it. By the early summer of 1966, 8,000 North Vietnamese Army troops a month were coming into South Vietnam. The communist troop contingent in South Vietnam reached 435,000 people: 46,300 North Vietnamese regulars, 114,000 Main Force Vietcong, 112,000 guerrillas, and more than 160,000 local militia. They did not need ice cream and bowling alleys, so the logistical requirements were simple. By 1966 they needed eight tons of supplies a day. They lived off the land and the peasants.

The supplies the communists could not get from South Vietnamese peasants came from the Soviet Union and China. During the early 1960s, when Nikita Khrushchev preached peaceful coexistence with the West, North Vietnam had gravitated toward the Chinese. But Khrushchev was ousted in 1964, and the new regime, headed by Leonid Brezhnev, was more interested in assisting North Vietnam. The Soviet Union and China were competing for leadership of the communist world, and neither could ignore the tiny ally against which the United States was conducting a major war. Moscow saw the American decision to escalate the war as an opportunity to diminish Chinese influence in Southeast Asia and augment its own. China supplied Hanoi with rice, trucks, AK-47 rifles, and 50,000 laborers; the USSR had sophisticated military technology—fighter aircraft, tanks, and surface-to-air missiles. North Vietnam exploited the Sino-Soviet split, and between 1965 and 1968 received more than $2 billion in assistance from the two powers.

The war's intensification undermined Johnson's political position and threatened his Great Society. At the end of 1965 there were 184,300 American troops in South Vietnam, with another 200,000 scheduled to arrive. Since 1959, 636 United States soldiers had died while another 6,400 were wounded, most of them in the previous two months.

The White House press corps added to Johnson's troubles. The journalists questioned everything. Throughout the 1964 election campaign Johnson had promised to avoid a land war in Asia, but the discrepancies between his promises in 1964 and his actions in 1965 were not the main reason for the growing hostility. Politicians rarely live up to election rhetoric. It was the lies that alienated reporters. Desperate to keep the war from gutting his Great Society, Johnson was trying to mislead the press. He had lied in the summer of 1964 about the incidents in the Gulf of Tonkin; in April 1965 he lied in denying that NSAM 328 had authorized offensive operations on the ground; and he lied repeatedly about the number of troops he was approving for combat in South Vietnam. On May 23, 1965, David Wise of the

New York Herald Tribune

coined the term“credibility gap,” and a few days later Murray Marder of the

Washington Post

amplified it.

Theological and social liberals in the main denominations reacted to the war, forming Clergy and Laymen Concerned About Vietnam to mobilize the religious community. It attracted some conservatives and radicals and functioned as one of the first important channels for Jewish and Catholic peace activism. Adopting a moderate tone and asserting its patriotic motivation, always careful to avoid extreme arguments and tactics, the clergy and layman's organization expressed its opposition in ways that kept it on good terms with its basically white, middle-class, religiously motivated constituency.

American university faculties were fertile ground for the antiwar movement. The intellectual left, inactive in the Eisenhower era, had been unable to function as an early critic of war policy, for its connections were too close with the liberal bipartisanship in diplomacy that followed World War II. A symbiotic relationship existed between the Kennedy administration and the intelligentsia, and Johnson began his presidency with noticeable attempts to court the intellectual community. That changed when Johnson ordered 3,000 marines into Danang on March 10, 1965, the first contingent of regular combat troops sent to Vietnam. At the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, several faculty members organized a“teach-in”—patterned after the famous 1960 civil rights sit-ins—for March 24, 1965. More than 3,500 students attended it. Similar teach-ins occurred at campuses across the country in the spring of 1965, culminating in the“National Teach-In” at 122 colleges and universities on May 15.

Students joined and went beyond faculty liberals. Johnson's lies and his calls for more troops, which disrupted or took the lives of American youths too poor to get college deferments, invaded the young on campus in another way, not lethally but devastatingly. They were the baby boomers, born in the wake of the Good War and reared in prosperity. They were better fed, better housed, and better educated than any previous generation. They thought that anything was possible, that the nation's problems—racial injustice, pockets of poverty, the cold war—would be solved. Optimism was their birthright. Johnson's war in Vietnam had no place in their world view. As the draft calls went out and the lies multiplied, they responded with anger and frustration. During the late 1950s and early 1960s a certain amount of discontent had been a rite of passage. Rock 'n' rollers rebelled against the music and the clothes of their parents; beats rebelled against materialism; college students rebelled against racism. Now rebellion took on a greater urgency still.

The most prominent of the campus antiwar organizations was the Students for a Democratic Society. SDS, founded in 1960 by a group of students politically associated with older leftists, was active in the civil rights movement. By 1964, especially after the Gulf of Tonkin incident, SDS began to organize campus demonstrations and teach-ins against the war and circulated petitions among draft-age men declaring“We Won't Go.” On April 17, 1965, SDS sponsored a demonstration in Washington, D.C., which brought more than 20,000 protesters to the city. During the next year, membership grew from 2,000 to nearly 30,000. Other groups, among them the Catholic Peace Fellowship, the Emergency Citizens' Group Concerned About Vietnam, Another Mother for Peace, and the National Emergency Committee of Clergy Concerned About Vietnam, joined the opposition to the war.

Many students ventured beyond talk. Some turned in their draft cards, others burned theirs. They played“tit-for-tat” with the government. As Johnson escalated the war, they escalated theirs. Berkeley students formed a draft resistance movement.“To cooperate with conscription is to perpetuate its existence, without which the government could not wage war,” announced an antiwar leader.“I choose to refuse to cooperate with the selective service,” wrote Dennis Sweeney,“because it is the only honest, whole, and human response I can make to a military institution which demands the allegiance of my life.”

Johnson was now facing two wars, both undeclared and both tearing at the heart of his domestic programs. Mounting casualties and the antiwar movement made the front-page news every day. To keep the political situation from worsening, Johnson decided not to call up the reserves, not to declare a national emergency, not to declare war, and not to tell the truth. When the time came to pay for the war, he chose not to raise taxes. Gordon Ackley, chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers, told him that the war was going to cost $3 billion a month in 1966. Johnson had either to reduce the war effort, to postpone Great Society domestic programs, or to raise taxes. Hoping the war would be over by the end of the year, he ignored the advice, financing the war and the Great Society with budget deficits.

Criticism intensified in Congress among liberal Democrats, whom Johnson needed to pass civil rights and antipoverty legislation.“There are limits to what we can do in helping any government surmount a Communist uprising,” Senator Frank Church of Idaho had warned the president in the spring of 1965.“If the people themselves will not support the government in power, we cannot save it.” The leading opponent was Senator J. William Fulbright of Arkansas. A Rhodes scholar and a former president of the University of Arkansas, Fulbright was the quintessential cerebral southerner, soft-spoken yet eloquent, politically astute but willing to take moral stands. Upon election to the Senate in 1944, Fulbright had become a close friend and ally of Lyndon Johnson, to the extent of helping the president steer the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution through the national legislature. But by 1965 Vietnam was dividing the two.